***REGION 24: Europe VI

ConversazioniReading Globally

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

1avaland

If you have not read the information on the master thread regarding the intent of these regional threads, please do this first.

***Europe VI: Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovenia

***Europe VI: Poland, Slovakia, Hungary, Czech Republic, Slovenia

2Trifolia

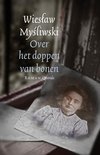

I'm reading Over het doppen van bonen by Wieslaw Mysliwski. It's an impressive monologue by an older man from Poland in which he reveals the story of his life. It's one of the weirdest books I've read so far this year, very enthralling also. I'm not sure if it has been translated in English yet, but it's a prize-winning book in Poland.

3rebeccanyc

Skylark by Dezső Kosztolányi 1924, translation ?, Hungarian

I found this novel, by turns, charming, satiric, and a little bit horrifying in its depiction of an extremely provincial town in Hungary at the end of the 19th century, in the waning years of the Austro-Hungarian empire, focusing on an aging couple and what they do when their ugly and somewhat stupid 35-ish daughter, Skylark, goes to stay with relatives "in the country" for a week. Kosztolányi has a telling eye for the descriptive detail and for the hypocrisy of many of the residents of the town, and the turnaround of the parents cleaning up the evidence of what they did while their child was away is quite funny. But it is a sad book too, and I can't help but find a little bit of a political edge in it as well.

I found this novel, by turns, charming, satiric, and a little bit horrifying in its depiction of an extremely provincial town in Hungary at the end of the 19th century, in the waning years of the Austro-Hungarian empire, focusing on an aging couple and what they do when their ugly and somewhat stupid 35-ish daughter, Skylark, goes to stay with relatives "in the country" for a week. Kosztolányi has a telling eye for the descriptive detail and for the hypocrisy of many of the residents of the town, and the turnaround of the parents cleaning up the evidence of what they did while their child was away is quite funny. But it is a sad book too, and I can't help but find a little bit of a political edge in it as well.

4Trifolia

105. Over het doppen van bonen (A Treatise on Shelling Beans) by Wieslaw Mysliwski

This must be one of the strangest books I've read this year. It is one brilliant monologue of an older man in which he tells an anonimous visitor his random thoughts, memories, insights while shelling beans. Little by little we get to know the man and his own history which is also the history of the common man in Poland.

Sometimes I was a bit overwhelmed by the prose which went on and on and on. The book really grabbed me at times, e.g. when the man talked of the drunk music-teacher who conducted the orchestra in silence, or of the dependant pig that was a metaphor of his happy childhood, or of the man who taught him how to play the saxophone, or of the girl from the Red Cross who helped him during the war, or of his uncle who committed suicide. Through his eyes and mouth you sense there is more to these people and, you feel the sorrow, pain, hope, joy and happiness of the individual.

The monologue is not linear and jumps back and forth through time, creating this beautiful, epic image of an ordinary life which proves that no life is ordinary once you dig a bit deeper.

It's a book you should read slowly. It's probably not everybody's cup of tea as it is rather hermetic at times, but if you take the time and are ready to put in the effort, you'll certainly be rewarded.

This must be one of the strangest books I've read this year. It is one brilliant monologue of an older man in which he tells an anonimous visitor his random thoughts, memories, insights while shelling beans. Little by little we get to know the man and his own history which is also the history of the common man in Poland.

Sometimes I was a bit overwhelmed by the prose which went on and on and on. The book really grabbed me at times, e.g. when the man talked of the drunk music-teacher who conducted the orchestra in silence, or of the dependant pig that was a metaphor of his happy childhood, or of the man who taught him how to play the saxophone, or of the girl from the Red Cross who helped him during the war, or of his uncle who committed suicide. Through his eyes and mouth you sense there is more to these people and, you feel the sorrow, pain, hope, joy and happiness of the individual.

The monologue is not linear and jumps back and forth through time, creating this beautiful, epic image of an ordinary life which proves that no life is ordinary once you dig a bit deeper.

It's a book you should read slowly. It's probably not everybody's cup of tea as it is rather hermetic at times, but if you take the time and are ready to put in the effort, you'll certainly be rewarded.

5rebeccanyc

Just posted this on your personal thread, but will copy it here:

I've just received a book by Wieslaw Mysliwski, Stone upon Stone, from my Archipelago Books subscription. It is quite a tome, so I'm going to have to wait until I have time to read it, especially now that I've read your comments and see it probably needs to be read slowly.

I've just received a book by Wieslaw Mysliwski, Stone upon Stone, from my Archipelago Books subscription. It is quite a tome, so I'm going to have to wait until I have time to read it, especially now that I've read your comments and see it probably needs to be read slowly.

6arubabookwoman

HUNGARY

A Journey Round My Skull by Frigyes Karinthy

In this book, Karinthy, a Hungarian writer, describes his diagnosis of and surgery to remove a brain tumor. Strangely enough, given the subject matter, it is a delightful read. Karinthy's sparkling personality and self-deprecating humor never desert him. He is a talented writer with an original way of saying things, and he never bores.

Poking a little fun at the world-reknowned surgeon who will operate on him he says, tongue in cheek: 'I found it a little humiliating that he was not interested in my own views about my condition. He probably regarded me as a layman who had no opinions on such matters, or perhaps, having heard that I was some kind of poet, he was on his guard against the vagaries of an overheated imagination.'

In fact, Karinthy tries to keep his imagination in check: 'When I put my questions, I used medical terms....I did not ask her what the cowering, terrified Being that lurked somewhere behind my tumour was so plaintively asking below the threshold of consciousness. I did not ask whether the patient screamed like a wild beast and struggled to escape when they split her skull open, whether her blood and brains came pouring out of the wound or whether at last the victim fainted on the torture rack, gasping for breath, with mouth open and staring eyes. Instead, I questioned her about the operation as if it had been some delicate experiment in physics or a job of repairs by a watchmaker.'

(This is about as gorey as the book gets, BTW).

As a writer, he came to realize that, 'for the first time in my life, I was to observe not for the sake of recording that personal vision which the artist calls 'truth'...but for the sake of reality, which remains reality even if we have no means of communicating its message. Never had I been so far from a lyrical state of mind as in this, the most subjective phase of my life."

A Journey Round My Skull by Frigyes Karinthy

In this book, Karinthy, a Hungarian writer, describes his diagnosis of and surgery to remove a brain tumor. Strangely enough, given the subject matter, it is a delightful read. Karinthy's sparkling personality and self-deprecating humor never desert him. He is a talented writer with an original way of saying things, and he never bores.

Poking a little fun at the world-reknowned surgeon who will operate on him he says, tongue in cheek: 'I found it a little humiliating that he was not interested in my own views about my condition. He probably regarded me as a layman who had no opinions on such matters, or perhaps, having heard that I was some kind of poet, he was on his guard against the vagaries of an overheated imagination.'

In fact, Karinthy tries to keep his imagination in check: 'When I put my questions, I used medical terms....I did not ask her what the cowering, terrified Being that lurked somewhere behind my tumour was so plaintively asking below the threshold of consciousness. I did not ask whether the patient screamed like a wild beast and struggled to escape when they split her skull open, whether her blood and brains came pouring out of the wound or whether at last the victim fainted on the torture rack, gasping for breath, with mouth open and staring eyes. Instead, I questioned her about the operation as if it had been some delicate experiment in physics or a job of repairs by a watchmaker.'

(This is about as gorey as the book gets, BTW).

As a writer, he came to realize that, 'for the first time in my life, I was to observe not for the sake of recording that personal vision which the artist calls 'truth'...but for the sake of reality, which remains reality even if we have no means of communicating its message. Never had I been so far from a lyrical state of mind as in this, the most subjective phase of my life."

7southernbooklady

HUNGARY

The Book of Fathers by Miklos Vamos is a sweeping epic of the Csillag family through twelve generations. They are a little bit haunted by a family trait that gives them flashes of both past and future events (sometimes very far into the past and very far into the future). Each patriarch writes about his life in what the family calls "the book of fathers" for the benefit of his future sons and grandsons.

Very beautiful, very smart, and often very funny amidst the backdrop of tragedy. Reviewed here, if anyone is interested.

The Book of Fathers by Miklos Vamos is a sweeping epic of the Csillag family through twelve generations. They are a little bit haunted by a family trait that gives them flashes of both past and future events (sometimes very far into the past and very far into the future). Each patriarch writes about his life in what the family calls "the book of fathers" for the benefit of his future sons and grandsons.

Very beautiful, very smart, and often very funny amidst the backdrop of tragedy. Reviewed here, if anyone is interested.

8rebeccanyc

Interesting, because I had a completely different reaction to The book of Fathers. Here's what I wrote in my review.

I wanted to read this book after I read a rave review by Jane Smiley in the New York Times Book Review. Alas, I was sorely disappointed. It is the story of 12 generations of a Hungarian family, focusing in each generation on the first-born son who, for most of the book, inherits the magical ability to see into the family's past and sometimes into the future; Hungarian history from the past 300 years is thrown in too. The novel irritated me for several reasons. First of all, it was way too formulaic: each generation is matched up with one of the 12 astrological signs, each chapter begins with a "poetic" look at what is happening in the natural world at the time of that astrological sign, etc. Second, the characters of each of the sons/fathers seemed wooden to me, designed to fit the history and the sign. Finally, I don't know whether it was the author or the translator, but there were a lot of odd, old-fashioned, or out-of-place words and, in the final section, some of which takes place in New York City, some things that were just plain wrong. Still, there was enough going on that I read the whole book just to see how it all worked out.

Edited to fix touchstone.

I wanted to read this book after I read a rave review by Jane Smiley in the New York Times Book Review. Alas, I was sorely disappointed. It is the story of 12 generations of a Hungarian family, focusing in each generation on the first-born son who, for most of the book, inherits the magical ability to see into the family's past and sometimes into the future; Hungarian history from the past 300 years is thrown in too. The novel irritated me for several reasons. First of all, it was way too formulaic: each generation is matched up with one of the 12 astrological signs, each chapter begins with a "poetic" look at what is happening in the natural world at the time of that astrological sign, etc. Second, the characters of each of the sons/fathers seemed wooden to me, designed to fit the history and the sign. Finally, I don't know whether it was the author or the translator, but there were a lot of odd, old-fashioned, or out-of-place words and, in the final section, some of which takes place in New York City, some things that were just plain wrong. Still, there was enough going on that I read the whole book just to see how it all worked out.

Edited to fix touchstone.

9southernbooklady

I actually thought the zodiac framework was lightly applied, and in fact almost lost in translation. As a structure, it felt no more formulaic to me than any other set of interlinked stories. I actually found myself thinking of Chaucer.

I thought the general progression of the characterizations of each generation developed from a kind of folkloric approach to the more modern psychological complexity we require of contemporary fiction. And I found the reactions of the Csillags/Sterns who went through the Holocaust to be very spot on. Both the father who renounced his heritage and his son who spends his life looking for what was lost.

It's worth noting that, as a rule, Jane Smiley and I don't have the same tastes in fiction. At least, that's what I decided after reading her Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel, where I disagreed with almost everything she said about every book.

I thought the general progression of the characterizations of each generation developed from a kind of folkloric approach to the more modern psychological complexity we require of contemporary fiction. And I found the reactions of the Csillags/Sterns who went through the Holocaust to be very spot on. Both the father who renounced his heritage and his son who spends his life looking for what was lost.

It's worth noting that, as a rule, Jane Smiley and I don't have the same tastes in fiction. At least, that's what I decided after reading her Thirteen Ways of Looking at the Novel, where I disagreed with almost everything she said about every book.

10Trifolia

Because of Rebecca's comments here I also read Skylark. This book is a little gem. The characters are somewhat sinister and tragic, the story sometimes humorous, sometimes sarcastic and it leaves the reader with plenty to think about. While the first book I read this year (Sisters of the Sinai) was all about looking for one's purpose that God has created and the joy that comes with it, this book is about the tragedy of people who don't even realize they have a purpose in life and take life as it comes. Recommended if you like literary, slow reading of quality.

(Thanks, Rebecca, for bringing this book to my attention).

(Thanks, Rebecca, for bringing this book to my attention).

11msjohns615

POLAND

I just finished Witold Gombrowicz's Ferdydurke, which tells the story of thirty year old Joey Kowalski, who is banished back to the age of seventeen by Professor Pimko. He's sent to school, where rival groups of students argue about whether a schoolboy should be innocent and pure or obscene and mature. He is sent to live with the Youngblood family, a modern couple with a beautiful daughter; then he goes to the countryside with one of his fellow students in search of a farmhand.

I was excited to read this book because Gombrowicz is something of a legend in the history of Argentine literature. He spent a quarter of a century in exile in Buenos Aires, and the original Spanish translation of this book, done by the author himself with the help of his friends in Buenos Aires, was influential on Argentine literature in the second half of the 20th century. I read a more recent English translation done by Danuta Borchardt, and I though it was hilarious and thought-provoking. I hope to find a copy of the Spanish translation soon and try it as well. It's definitely a unique and fun book.

I just finished Witold Gombrowicz's Ferdydurke, which tells the story of thirty year old Joey Kowalski, who is banished back to the age of seventeen by Professor Pimko. He's sent to school, where rival groups of students argue about whether a schoolboy should be innocent and pure or obscene and mature. He is sent to live with the Youngblood family, a modern couple with a beautiful daughter; then he goes to the countryside with one of his fellow students in search of a farmhand.

I was excited to read this book because Gombrowicz is something of a legend in the history of Argentine literature. He spent a quarter of a century in exile in Buenos Aires, and the original Spanish translation of this book, done by the author himself with the help of his friends in Buenos Aires, was influential on Argentine literature in the second half of the 20th century. I read a more recent English translation done by Danuta Borchardt, and I though it was hilarious and thought-provoking. I hope to find a copy of the Spanish translation soon and try it as well. It's definitely a unique and fun book.

12Polaris-

My first post in this section of the Reading Globally group - hello one and all! Really enjoying my first Alan Furst novel - The Polish Officer - it's still early days, but the mood and flavour of occupied Poland during WW2 really comes across. Scenes have both a rural and urban setting and the writing is very good. A satisfying read so far - hope it's as rewarding to the finish.

13labfs39

59. The Pathseeker by Imre Kertesz

This short novella by Nobel Prize winning author, Imre Kertesz, is a different approach to the question of responsibility and guilt in the 20th century. The story begins with "the commissioner", the only name by which we are to know him, interviewing the owner of a hotel about an incident that happened nearby. The hotel owner has lived in the town since boyhood and volunteers information rather feverishly. In fact, he seems relieved to be able to confess his "small part in universal evil", and furthermore to explain his inaction since then. But the commissioner has not come to absolve the hotel owner, rather his intent is to visit the nearby site of the incident, and then continue on his way to a seaside resort with his wife.

The visit to the unnamed site turns out to be a disappointment, however. Nothing remains as it was, and the

Tourists were like ants, diligently carrying off the significance of things, crumb by crumb, wearing away a bit of the unspoken importance investing them with every word they spoke and every single snapshot they took. He should have realized that this was precisely the sort of opportunity they would not leave unexploited.

The commissioner does not find the evidence he is seeking here.

He does, however, spot a veiled woman in the distance with whom he is later to have an unexpected conversation. The woman is mysterious and accusatory. When the commissioner protests that he was only at the site by chance, the woman replies, "There's no such thing as chance. Only injustice." Now it is the commissioner's turn to protest his innocence; but the veiled woman is as uninterested in his excuses as the commissioner was in the hotel owner's.

Finally, spurning his confused but supportive wife, the commissioner seeks to complete his mission by visiting the factory. Finding the factory still working, he feels a brief moment of hope, but then realizes that he has still failed, because all that remains are objects. What is the truth he seeks?

These objects here were holding their peace; like uncommunicative strangers, they were complete and sufficient unto themselves, they were not going to verify his existence. Let him find it in chance or seek it within himself, accept it or reject it-that was now, as ever, a matter of utter indifference to this pitiless landscape and to these obtusely different objects here.

As he waits for the train back to town, he picks up a paper and reads an article about a recent suicide. With that, the commissioner has a moment of panic, but "surely he couldn't be looking for his accusers?" His mission, however, appears complete, and he continues forward, in seeming indifference to all that he has experienced in the last few days.

Kertesz is masterful at exploring the themes of responsibility and guilt without ever becoming specific. By doing so, the unnamed places and people can stand for everyone, for each of us. We all have a role in the story be it spectator, victim, survivor, or tourist. Vague, confusing, and surreal, the story prods the reader to identify with the scenario and ask hard questions of ourselves. Although I can't say I enjoyed this novella, it did make me uncomfortable, and that, I think, is the point.

14Polaris-

The Polish Officer was a very enjoyable bit of escapist reading. Alan Furst is a master at generating authentic atmosphere in this espionage novel which spans the first two years of WW2 from Poland to France and back again.

15rebeccanyc

They Were Counted by Miklós Bánffy

HUNGARY, originally published in 1937, English translation 2000

I almost gave up on this book soon after I started it, because I wasn't that interested in the big party of aristocrats at a Hungarian castle in the early years of the 20th century with which it begins. But I kept at it and soon I was hooked, because Bánffy is a marvelous story teller. It is a sprawling tale, with two cousins at its center, but involving dozens of other characters and their relationships, romantic and otherwise, and politics. What makes the book so fascinating, aside from or despite the almost soap-opera-ish aspects of some of the subplots, is the look at the vanished (perhaps deservedly so) world of pre-World War I Hungary and, in particular, the often fought-over province of Transylvania, then under Hungarian rule but largely peopled by ethnic Romanians. These were the waning years of the Austro-Hungarian empire, much written about by Austrians such as Joseph Roth, but this book is told from the Hungarian perspective, and the Hungarians very much felt themselves second-class citizens in the empire. The descriptions of political events, many presumably based on real ones, since Bánffy had himself been a politician from an ancient aristocratic family, show the futility of the political arguments of the time, all focused on the Hungarians' resentment of the Austrian rulers, completely oblivious to the changes in the world outside. (It is my understanding that the next two volumes of this trilogy lead up to and end with the killing of Archduke Ferdinand and the beginning of first world war, which was the death knell of the Austro-Hungarian empire.)

While the stories of the cousins and their families, their lovers and those they want to to be their lovers, their land and their financial issues are, along with the politics, the heart of the novel, I also found the parts dealing with the beauty of the Transylvanian landscape and the lives of peasants, especially those in the mountains, very interesting. What was also interesting, and depressing, was the extremely limited lives women had to lead in those times, the still existing emphasis on the role and importance of the hereditary aristocracy, and the power those aristocrats had over the lives of others.

Despite the blurbs on the copy I have, which compare Bánffy to Tolstoy, this isn't in the same literary league. Part of this may be due to the translation since the English translator (who worked with Bánffy's daughter) says in his introduction that he not only cut parts of the book because it was so long and politically detailed, but also that he realized that "a literal translation in English would give none of the quality of the original and would fail completely to give any idea of the idiom and feeling of the first years of this century in Central Europe . . . anyone tackling it would have to make an English version rather than a literal translation." Nonetheless, it is a compellingly readable story and I am eager to read the next two volumes.

Finally, the edition I read is marred by sloppy proofreading -- words missing, words where they don't belong, typos and/or missed punctuation. It's a shame.

HUNGARY, originally published in 1937, English translation 2000

I almost gave up on this book soon after I started it, because I wasn't that interested in the big party of aristocrats at a Hungarian castle in the early years of the 20th century with which it begins. But I kept at it and soon I was hooked, because Bánffy is a marvelous story teller. It is a sprawling tale, with two cousins at its center, but involving dozens of other characters and their relationships, romantic and otherwise, and politics. What makes the book so fascinating, aside from or despite the almost soap-opera-ish aspects of some of the subplots, is the look at the vanished (perhaps deservedly so) world of pre-World War I Hungary and, in particular, the often fought-over province of Transylvania, then under Hungarian rule but largely peopled by ethnic Romanians. These were the waning years of the Austro-Hungarian empire, much written about by Austrians such as Joseph Roth, but this book is told from the Hungarian perspective, and the Hungarians very much felt themselves second-class citizens in the empire. The descriptions of political events, many presumably based on real ones, since Bánffy had himself been a politician from an ancient aristocratic family, show the futility of the political arguments of the time, all focused on the Hungarians' resentment of the Austrian rulers, completely oblivious to the changes in the world outside. (It is my understanding that the next two volumes of this trilogy lead up to and end with the killing of Archduke Ferdinand and the beginning of first world war, which was the death knell of the Austro-Hungarian empire.)

While the stories of the cousins and their families, their lovers and those they want to to be their lovers, their land and their financial issues are, along with the politics, the heart of the novel, I also found the parts dealing with the beauty of the Transylvanian landscape and the lives of peasants, especially those in the mountains, very interesting. What was also interesting, and depressing, was the extremely limited lives women had to lead in those times, the still existing emphasis on the role and importance of the hereditary aristocracy, and the power those aristocrats had over the lives of others.

Despite the blurbs on the copy I have, which compare Bánffy to Tolstoy, this isn't in the same literary league. Part of this may be due to the translation since the English translator (who worked with Bánffy's daughter) says in his introduction that he not only cut parts of the book because it was so long and politically detailed, but also that he realized that "a literal translation in English would give none of the quality of the original and would fail completely to give any idea of the idiom and feeling of the first years of this century in Central Europe . . . anyone tackling it would have to make an English version rather than a literal translation." Nonetheless, it is a compellingly readable story and I am eager to read the next two volumes.

Finally, the edition I read is marred by sloppy proofreading -- words missing, words where they don't belong, typos and/or missed punctuation. It's a shame.

16rebeccanyc

HUNGARY Originally published 1937 and 1940 English translation 2000

They Were Found Wanting by Miklós Bánffy

They Were Divided by Miklós Bánffy

These two novels complete the trilogy begun with They Were Counted and everything I said in my review of that book, above, holds true for these as well.

They Were Found Wanting takes the protagonist, Balint Abady, his cousin Laszlo, and dozens of other characters from the years 1906 to about 1909. As with the earlier volume, their stories and romances are mixed with set pieces of huge parties and hunts, politics within Hungary and in the broader Austro-Hungarian empire, and vivid descriptions of natural environments around the country. What comes out more strongly in this volume is the self-centeredness of Hungarian politics and the internal conflicts that blind people to the larger world outside, as well as Bánffy's goal of painting a complete portrait of a complex world that no longer existed by the time he wrote the novels in the 1930s.

The final, slimmer volume, They Were Divided, covers the period up until the first world war. In this novel, the personal stories continue, as do the political maneuverings and the portraits of nature, but there is also an overwhelming sense of loss and of a period ending, both for individuals and for the country. Bánffy completed this novel in 1940, as a second world war, which would destroy what the first one hadn't, was starting to ravage Europe.

One of Bánffy's points throughout these novels is the impotence of the Hungarian legislature, tied up in partisan politics and obstructionist policies that ignore the good of the country. A reader in the US can't help but see parallels to our own Congress.

They Were Found Wanting by Miklós Bánffy

They Were Divided by Miklós Bánffy

These two novels complete the trilogy begun with They Were Counted and everything I said in my review of that book, above, holds true for these as well.

They Were Found Wanting takes the protagonist, Balint Abady, his cousin Laszlo, and dozens of other characters from the years 1906 to about 1909. As with the earlier volume, their stories and romances are mixed with set pieces of huge parties and hunts, politics within Hungary and in the broader Austro-Hungarian empire, and vivid descriptions of natural environments around the country. What comes out more strongly in this volume is the self-centeredness of Hungarian politics and the internal conflicts that blind people to the larger world outside, as well as Bánffy's goal of painting a complete portrait of a complex world that no longer existed by the time he wrote the novels in the 1930s.

The final, slimmer volume, They Were Divided, covers the period up until the first world war. In this novel, the personal stories continue, as do the political maneuverings and the portraits of nature, but there is also an overwhelming sense of loss and of a period ending, both for individuals and for the country. Bánffy completed this novel in 1940, as a second world war, which would destroy what the first one hadn't, was starting to ravage Europe.

One of Bánffy's points throughout these novels is the impotence of the Hungarian legislature, tied up in partisan politics and obstructionist policies that ignore the good of the country. A reader in the US can't help but see parallels to our own Congress.

17Trifolia

Czech Republic: No Saints or Angels by Ivan Klima

One-sentence-summary

A middle-aged dentist, her daughter and her boyfriend are trying to give meaning to their lives in Prague in the 1990s.

My personal thoughts

One of the great things about my European challenge (as well as the global one) is that I get to read books I would never have picked up otherwise. Most of the times, the books are ok because I do evaluate them a bit beforehand, but sometimes I find a book I'll gladly classify as a favourite. No Saints or Angels is one of them. I know the one-sentence-summary sounds awful and not very appealing but it's very misleading because it's actually a story told from three different points of view that gives insight into what life is all about, the insecurities, the search for happiness, the lies, self-esteem, confidence, trust, etc. It also deals with the history of a family and a country. Klima is a great writer. He manages to portray characters in a few lines and to convey the feelings that ordinary human beings have without being heavy-handed. There's no real beginning and no real ending to this story but there are so many thoughts and insights that make it wortwhile. It's a brilliant mixture of humour and food for thought and that's more than enough for me.

One-sentence-summary

A middle-aged dentist, her daughter and her boyfriend are trying to give meaning to their lives in Prague in the 1990s.

My personal thoughts

One of the great things about my European challenge (as well as the global one) is that I get to read books I would never have picked up otherwise. Most of the times, the books are ok because I do evaluate them a bit beforehand, but sometimes I find a book I'll gladly classify as a favourite. No Saints or Angels is one of them. I know the one-sentence-summary sounds awful and not very appealing but it's very misleading because it's actually a story told from three different points of view that gives insight into what life is all about, the insecurities, the search for happiness, the lies, self-esteem, confidence, trust, etc. It also deals with the history of a family and a country. Klima is a great writer. He manages to portray characters in a few lines and to convey the feelings that ordinary human beings have without being heavy-handed. There's no real beginning and no real ending to this story but there are so many thoughts and insights that make it wortwhile. It's a brilliant mixture of humour and food for thought and that's more than enough for me.

18rebeccanyc

Hungary

The Adventures of Sindbad by Gyula Krúdy Written between 1911 and 1919, first published 1944, translation 1998

As Sindbad, an inveterate seducer and lover of women, travels (largely as a ghost), searching for his lost loves, and loving and erotically recalls their appearances and personalities, Krúdy is really exploring the loss of a centuries-old culture. It is the waning days of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and change is accelerating and inevitable, but the ancestors whose portraits hang on the walls of ancient homes and the dead in their graves are almost as real as the living.

As in his fascinating and mysterious Sunflower, Krúdy brilliantly evokes the beauty of the Hungarian countryside, the almost soporific quality of life in small villages, the bustling activity in Budapest (or, Buda and Pest) and, in this work, the characters of a huge number of women. As with Sunflower, very little is straightforward. At various times, Sindbad is alive and 300 years old, buried in a grave, traveling as a ghost in a carriage, and even transformed into a sprig of mistletoe. The boundary between life and death is porous, connected by love and longing.

Above all, there is a feeling of melancholy and loss. The stories abound with autumn leaves, dark nights illuminated by the moon, misty landscapes, rivers begging to be jumped into, men and women who have killed themselves for love. Musing about one of his loves, Sindbad recalls that she called him not "to the enjoyments of a quiet life, but rather to death, decay and annihilation, to the dance to exhaustion at the ball of life where the masked guests are encouraged to lie, cheat and steal, to push old people aside, to mislead the inexperienced young, and always to lie and weep alone . ."

The Adventures of Sindbad by Gyula Krúdy Written between 1911 and 1919, first published 1944, translation 1998

As Sindbad, an inveterate seducer and lover of women, travels (largely as a ghost), searching for his lost loves, and loving and erotically recalls their appearances and personalities, Krúdy is really exploring the loss of a centuries-old culture. It is the waning days of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and change is accelerating and inevitable, but the ancestors whose portraits hang on the walls of ancient homes and the dead in their graves are almost as real as the living.

As in his fascinating and mysterious Sunflower, Krúdy brilliantly evokes the beauty of the Hungarian countryside, the almost soporific quality of life in small villages, the bustling activity in Budapest (or, Buda and Pest) and, in this work, the characters of a huge number of women. As with Sunflower, very little is straightforward. At various times, Sindbad is alive and 300 years old, buried in a grave, traveling as a ghost in a carriage, and even transformed into a sprig of mistletoe. The boundary between life and death is porous, connected by love and longing.

Above all, there is a feeling of melancholy and loss. The stories abound with autumn leaves, dark nights illuminated by the moon, misty landscapes, rivers begging to be jumped into, men and women who have killed themselves for love. Musing about one of his loves, Sindbad recalls that she called him not "to the enjoyments of a quiet life, but rather to death, decay and annihilation, to the dance to exhaustion at the ball of life where the masked guests are encouraged to lie, cheat and steal, to push old people aside, to mislead the inexperienced young, and always to lie and weep alone . ."

19rebeccanyc

Poland

In Red by Magdalena Tulli Published 1998, English translation 2001

I nearly missed my subway stop two days in a row because I was so caught up in the unreal world Magdalena Tulli creates in this gem of a novella that is nonetheless very hard to describe. At the start, the Polish town of Stitchings is always cold and snowy and almost always dark, and it is suspended in an unclear time. Gradually, some of the people of the town come into focus, and the time resolves to around the time of the first world war (although Stitichings is part of a mythical fourth partition of Poland, ruled by the Swedes who are said to be better than the Germans and the Russians). People die but stay alive, businesses thrive and then fall apart, grudges are held for a long time, circus monkeys pass out counterfeit bills, what seems at first to be a small town apparently grows to include many more people of varying kinds, time passes and times get hard and then better and then hard again, the weather changes and it is hot and sunny all day and all night, a bustling port appears but then disappears . . . and so on. Overall, the tone is gloomy, and much that happens is grim, as many characters die, but fun and mysterious things happen too.

What makes this book so remarkable is Tulli's writing. She meshes crystal clear descriptions of people, their actions, and their environment with illusion and allusion, in prose that flows so naturally that even completely unnatural events seem perfectly believable. People can seem real and ephemeral at the same time, even as people who die don't necessarily stay dead. Music plays an important role in the book too, with the sounds of different instruments adding insight into what is going on with different characters. Tulli creates a story that seems grounded in some ways in Poland in the first half of the 20th century but then takes off from there into an into an alternate world of imagination. Having finished this book, I could easily start it all over again, and I'll be looking for other works by Tulli.

In Red by Magdalena Tulli Published 1998, English translation 2001

I nearly missed my subway stop two days in a row because I was so caught up in the unreal world Magdalena Tulli creates in this gem of a novella that is nonetheless very hard to describe. At the start, the Polish town of Stitchings is always cold and snowy and almost always dark, and it is suspended in an unclear time. Gradually, some of the people of the town come into focus, and the time resolves to around the time of the first world war (although Stitichings is part of a mythical fourth partition of Poland, ruled by the Swedes who are said to be better than the Germans and the Russians). People die but stay alive, businesses thrive and then fall apart, grudges are held for a long time, circus monkeys pass out counterfeit bills, what seems at first to be a small town apparently grows to include many more people of varying kinds, time passes and times get hard and then better and then hard again, the weather changes and it is hot and sunny all day and all night, a bustling port appears but then disappears . . . and so on. Overall, the tone is gloomy, and much that happens is grim, as many characters die, but fun and mysterious things happen too.

What makes this book so remarkable is Tulli's writing. She meshes crystal clear descriptions of people, their actions, and their environment with illusion and allusion, in prose that flows so naturally that even completely unnatural events seem perfectly believable. People can seem real and ephemeral at the same time, even as people who die don't necessarily stay dead. Music plays an important role in the book too, with the sounds of different instruments adding insight into what is going on with different characters. Tulli creates a story that seems grounded in some ways in Poland in the first half of the 20th century but then takes off from there into an into an alternate world of imagination. Having finished this book, I could easily start it all over again, and I'll be looking for other works by Tulli.

20Trifolia

Hungary: De nacht voor de scheiding (Válás Budán) by Sandor Marai

This book, first published in 1935, deals with 12 hours in the life of a middle-aged Hungarian judge who prepares to settle the divorce of an acquaintance and his wife he briefly met years ago. In the first part of the book, we get to know the judge, his life, his history and his formal way of thinking, in the second part, we see his encounter with his acquaintance, a doctor, who pays him a nightly visit.

Basically this book deals with the universal themes of ratio vs. feelings, old vs. new, man vs. woman. Marai wraps this up in beautiful prose and razor-sharp observation which turn this book into a brilliant psychological novel. Highly recommended.

This book, first published in 1935, deals with 12 hours in the life of a middle-aged Hungarian judge who prepares to settle the divorce of an acquaintance and his wife he briefly met years ago. In the first part of the book, we get to know the judge, his life, his history and his formal way of thinking, in the second part, we see his encounter with his acquaintance, a doctor, who pays him a nightly visit.

Basically this book deals with the universal themes of ratio vs. feelings, old vs. new, man vs. woman. Marai wraps this up in beautiful prose and razor-sharp observation which turn this book into a brilliant psychological novel. Highly recommended.

21rebeccanyc

Poland Originally published 1992; English translation 2004

Dreams and Stones by Magdalena Tulli

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

When I read Tulli's In Red last year, I was so absorbed in her creation of an unreal world filled with clearly envisioned people, beautiful writing, and illusion and allusion that I nearly missed my subway stop twice. This novella, her first, also is filled with beautifully poetic writing and illusion and allusion, but I never got that absorbed in it. I am impressed by what Tulli has accomplished, but I am quite sure that I really didn't understand a lot of it.

The book describes the creation, life, and decay of an unnamed city which, as the novella progresses, appears to be a mythical version of Warsaw (described as a city with the straight lines of W's and A's in its name). In the beginning, the dichotomy of tree-like growth (natural, uncontrolled, always branching, balanced by an equally large root system) versus machine-made growth (human-directed, controlled, always increasing, balanced by an "anti-city") is established, and later the dichotomy of dreams and stones. At times the city seems to grow to encompass the world, and the skies and the stars; at times later in the book, it both seems to contain other (named) cities and to be apart from them. There are times when the mood of the people is described, but they are always spoken of generally; there are no individual characters. This description is much more straightforward than the book itself!

As the city grows, there were places where I felt Tulli was commenting on some of the history and politics of Warsaw and Poland itself, although I am not familiar enough with that to catch more than a few allusions. Certainly the determination to destroy the anti-city could allude to the communist era, as could the awards for manual and machine workers who accomplished a lot in little time. The choice of train lines heading east (to Russia) or west (to Paris) could refer to different pulls on the Polish people. But I have to stress that all of this happens in the most allusive way, so it is possible to understand it in different ways.

Tulli's writing is poetic, and a delight to read, and this book is more a collection of imagery and a parable than a novel. Some of the recurring images and ideas are architecture and lines (straight versus meandering), shifts in time and space (also true of In Red), the ephemeral quality of dreams (and us?) and the permanence of stone. Other readers have commented that Tulli has translated Calvino and that there are echoes of his Invisible Cities in this book; I have that on the TBR and will get to it soon.

All in all, I am glad I read this book, but I'm especially glad I read In Red first, as I would not have been so enthusiastic about Tulli I had come to this one first.

Dreams and Stones by Magdalena Tulli

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

When I read Tulli's In Red last year, I was so absorbed in her creation of an unreal world filled with clearly envisioned people, beautiful writing, and illusion and allusion that I nearly missed my subway stop twice. This novella, her first, also is filled with beautifully poetic writing and illusion and allusion, but I never got that absorbed in it. I am impressed by what Tulli has accomplished, but I am quite sure that I really didn't understand a lot of it.

The book describes the creation, life, and decay of an unnamed city which, as the novella progresses, appears to be a mythical version of Warsaw (described as a city with the straight lines of W's and A's in its name). In the beginning, the dichotomy of tree-like growth (natural, uncontrolled, always branching, balanced by an equally large root system) versus machine-made growth (human-directed, controlled, always increasing, balanced by an "anti-city") is established, and later the dichotomy of dreams and stones. At times the city seems to grow to encompass the world, and the skies and the stars; at times later in the book, it both seems to contain other (named) cities and to be apart from them. There are times when the mood of the people is described, but they are always spoken of generally; there are no individual characters. This description is much more straightforward than the book itself!

As the city grows, there were places where I felt Tulli was commenting on some of the history and politics of Warsaw and Poland itself, although I am not familiar enough with that to catch more than a few allusions. Certainly the determination to destroy the anti-city could allude to the communist era, as could the awards for manual and machine workers who accomplished a lot in little time. The choice of train lines heading east (to Russia) or west (to Paris) could refer to different pulls on the Polish people. But I have to stress that all of this happens in the most allusive way, so it is possible to understand it in different ways.

Tulli's writing is poetic, and a delight to read, and this book is more a collection of imagery and a parable than a novel. Some of the recurring images and ideas are architecture and lines (straight versus meandering), shifts in time and space (also true of In Red), the ephemeral quality of dreams (and us?) and the permanence of stone. Other readers have commented that Tulli has translated Calvino and that there are echoes of his Invisible Cities in this book; I have that on the TBR and will get to it soon.

All in all, I am glad I read this book, but I'm especially glad I read In Red first, as I would not have been so enthusiastic about Tulli I had come to this one first.

22kidzdoc

Great review of Dreams and Stones, Rebecca. I still haven't read In Red yet, although I did enjoy Flaw.

23rebeccanyc

POLAND

Ashes and Diamonds by Jerzy Andrzejewski

Originally published 1948; English translation 1962; my edition 1991.

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

Originally published in 1948, and considered one of the best Polish postwar novels, Ashes and Diamonds takes place in a Polish town in the days just before and after the German surrender in May 1945. The Soviet army has liberated the town from the Nazis, and it is still unclear what exactly will happen. The town is awash in former Polish Home Army soldiers (although unnamed as such since the Soviets had already taken over by the time of publication), local and Soviet communists, bureaucrats looking to advance, a somewhat discomfited aristocracy, returnees from Nazi concentration camps, teenagers who grew up in the chaos of the war and seem to have no values, those who seek to make money no matter who is in power, and of course regular folks. The novel switches back and forth between various people and their stories, and it takes a little while to figure out who is who and how they are connected.

Essentially, Andrzewjewski portrays people who have had to confront issues of ethics and conscience during the war, or are continuing to confront them, and how they individually decide to act. There are plots to kill people, plots to betray people, and yet people are intertwined in ways that can be awkward, at best, in the fluid situation; for example, the head of the local communists, mourning the death of his wife in a concentration camp, has to tell her sister about her death, and the sister is one of the local aristocrats. Everyone comes together at the town's hotel, the Monopole, which is striving to recapture prewar days, and they all certainly drink as if there is no tomrrow.

The title of the novel comes from a poem by Cyprian Norwid, that asks:

"Will only ashes and confusion remain,

Leading into the abyss? -- or will there be

In the depths of the ash, a star-like diamond,

The dawning of eternal victory!

It is hard to see the diamond in these ashes.

The edition I read had two introductions: one, by Heinrich Böll, written for an earlier edition, before the Wall came down, and one written by Barbara Niemczyk in the post-Communist era. Both point out that, for Polish readers would have immediately understood the unexpressed reality that the Soviets who "liberated" Poland were the same Soviets who occupied it in the days of the Hitler-Stalin nonaggression pact. In addition, Niemczyk notes some errors in the translation, including two long sections that were omitted by the original translator. Finally, I found it disconcerting that the Polish names were "translated" into English (sometimes incorrectly as Niemczyk points out); for example, the Polish name Maciek becomes Michael and Jerzy becomes Julius. I would have preferred it if the translator kept the Polish names.

Ashes and Diamonds by Jerzy Andrzejewski

Originally published 1948; English translation 1962; my edition 1991.

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

Originally published in 1948, and considered one of the best Polish postwar novels, Ashes and Diamonds takes place in a Polish town in the days just before and after the German surrender in May 1945. The Soviet army has liberated the town from the Nazis, and it is still unclear what exactly will happen. The town is awash in former Polish Home Army soldiers (although unnamed as such since the Soviets had already taken over by the time of publication), local and Soviet communists, bureaucrats looking to advance, a somewhat discomfited aristocracy, returnees from Nazi concentration camps, teenagers who grew up in the chaos of the war and seem to have no values, those who seek to make money no matter who is in power, and of course regular folks. The novel switches back and forth between various people and their stories, and it takes a little while to figure out who is who and how they are connected.

Essentially, Andrzewjewski portrays people who have had to confront issues of ethics and conscience during the war, or are continuing to confront them, and how they individually decide to act. There are plots to kill people, plots to betray people, and yet people are intertwined in ways that can be awkward, at best, in the fluid situation; for example, the head of the local communists, mourning the death of his wife in a concentration camp, has to tell her sister about her death, and the sister is one of the local aristocrats. Everyone comes together at the town's hotel, the Monopole, which is striving to recapture prewar days, and they all certainly drink as if there is no tomrrow.

The title of the novel comes from a poem by Cyprian Norwid, that asks:

"Will only ashes and confusion remain,

Leading into the abyss? -- or will there be

In the depths of the ash, a star-like diamond,

The dawning of eternal victory!

It is hard to see the diamond in these ashes.

The edition I read had two introductions: one, by Heinrich Böll, written for an earlier edition, before the Wall came down, and one written by Barbara Niemczyk in the post-Communist era. Both point out that, for Polish readers would have immediately understood the unexpressed reality that the Soviets who "liberated" Poland were the same Soviets who occupied it in the days of the Hitler-Stalin nonaggression pact. In addition, Niemczyk notes some errors in the translation, including two long sections that were omitted by the original translator. Finally, I found it disconcerting that the Polish names were "translated" into English (sometimes incorrectly as Niemczyk points out); for example, the Polish name Maciek becomes Michael and Jerzy becomes Julius. I would have preferred it if the translator kept the Polish names.

24rebeccanyc

POLAND

Moving Parts by Magdalena Tulli (Originally published 2003, English translation 2005)

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

In this playful and perceptive novella, Tulli explores what it means to pluck a story out of life, how fiction and reality intersect, and how the past enters the present, and the difficulty, if not impossibility, of telling a story that really represents life. She does this by creating the character of "the narrator," a man who has been hired by some mysterious person or organization to write a story. From the beginning, when the "narrator" tries to figure out who his characters are, he is out of his depth, as the "characters" go off and do things he doesn't necessarily want them to do, as more "characters" enter the "story," and as he finds his way through streets, buildings, stairways, elevators, and basements to try to both follow and constrain them. The time frame is fractured too, as the beginning of the novella seems to be in the present, but towards the end the "characters," including the "narrator," find themselves in wartime Poland, possibly during the Warsaw uprising.

In between, Tulli and the "narrator" meditate on language and grammar, on how they shape both the story and reality. For example, Tulli writes:

The narrator hopes that at this point he'll finally be able to put his foot on the dry land of the past tense, in the kingdom of certainty where facts live and flourish. Only there do they flourish, nowhere else: the past tense is their entire world, the homeland of truths that are incontrovertible though, it must be admitted, usually contradictory. p. 23

They (two of the "characters") would make some tea, and sit in the armchairs, teacups in hand, discussing the worrying suspicion that they would have to relinquish their polished floors and their phonograph and record collection, and they continually cast doubt on something that was blindingly obvious given the ineluctable way in which the future tense turns into the past. They even tried to joke about this process, but their jokes were not entirely successful; they were not funny enough for them to convince themselves they were safely beyond the reach of grammar. p. 95

This is the third of Tulli's books that I've read. All have been fascinating, all have been different. But, in all of them, Tulli writes beautiful, occasionally poetic prose and is an extremely detailed observer of the world around her, particularly of color and architecture, human activities and home furnishings. This was a delightful and thought-provoking read.

Moving Parts by Magdalena Tulli (Originally published 2003, English translation 2005)

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

In this playful and perceptive novella, Tulli explores what it means to pluck a story out of life, how fiction and reality intersect, and how the past enters the present, and the difficulty, if not impossibility, of telling a story that really represents life. She does this by creating the character of "the narrator," a man who has been hired by some mysterious person or organization to write a story. From the beginning, when the "narrator" tries to figure out who his characters are, he is out of his depth, as the "characters" go off and do things he doesn't necessarily want them to do, as more "characters" enter the "story," and as he finds his way through streets, buildings, stairways, elevators, and basements to try to both follow and constrain them. The time frame is fractured too, as the beginning of the novella seems to be in the present, but towards the end the "characters," including the "narrator," find themselves in wartime Poland, possibly during the Warsaw uprising.

In between, Tulli and the "narrator" meditate on language and grammar, on how they shape both the story and reality. For example, Tulli writes:

The narrator hopes that at this point he'll finally be able to put his foot on the dry land of the past tense, in the kingdom of certainty where facts live and flourish. Only there do they flourish, nowhere else: the past tense is their entire world, the homeland of truths that are incontrovertible though, it must be admitted, usually contradictory. p. 23

They (two of the "characters") would make some tea, and sit in the armchairs, teacups in hand, discussing the worrying suspicion that they would have to relinquish their polished floors and their phonograph and record collection, and they continually cast doubt on something that was blindingly obvious given the ineluctable way in which the future tense turns into the past. They even tried to joke about this process, but their jokes were not entirely successful; they were not funny enough for them to convince themselves they were safely beyond the reach of grammar. p. 95

This is the third of Tulli's books that I've read. All have been fascinating, all have been different. But, in all of them, Tulli writes beautiful, occasionally poetic prose and is an extremely detailed observer of the world around her, particularly of color and architecture, human activities and home furnishings. This was a delightful and thought-provoking read.

25StevenTX

HUNGARY

Opium and Other Stories by Géza Csáth

Stories written in Hungarian 1908 to 1912

English translation by Jascha Kessler and Charlotte Rogers 1980

Géza Csáth, born 1887, was an upper middle class Hungarian who showed considerable talent as an artist, writer, musician and composer before deciding of his own volition to enter medical school. He devoted his early career to researching the origins of mental disorders, a fascination which carries over to the short stories he was writing at the time. At the same time, however, Csáth became addicted to opium. During the First World War he began his own descent into insanity. In 1919 he killed his wife, was institutionalized, escaped, and then killed himself.

Csáth's short stories are a mixture of the tragic, the absurd, the macabre and the fantastic. The author's mother died when he was a young child, leading evidently to a sense of betrayal that caused him to depict mothers as uncaring. Children are often the principal subjects of his stories, and they are typically angry and sadistic, wreaking violence and death on their pets, their siblings, and especially their mothers. In other stories young men are tantalized with the prospect of sexual pleasures, only to be thwarted by indifferent females, by their own inhibitions, or by waking at the wrong moment to find it was all a dream.

Csáth is not entirely misogynistic, however. In "Festal Slaughter" he presents a remarkably sensitive portrait of a servant girl who must rise in the freezing dawn to prepare for the slaughter of a sow by a visiting butcher. Along with her employer's family she works to exhaustion that day processing the carcass, making sausages, etc., only to be casually raped by the butcher before he leaves. She is just as much a piece of meat to her culture as the sow.

In the title story, "Opium," Csáth praises his favorite drug. Sure it shortens your life, he argues, but it slows time and extends the pleasures of each day. You may live, at most, for ten years, but in those ten years you will experience twenty million years of bliss before letting "your head fall on the icy pillow of eternal annihilation." Other stories present perhaps a more cautionary picture of addiction, such as one in which the narrator is plagued by dreams of a giant, fearsome toad in his kitchen.

There is a bit of black comedy in the collection as well, such as in the story "Father, Son" where a young man returns to Hungary from America to retrieve his father's skeleton from a medical college where it has just been put on display in a classroom. There is social satire too, such as the story "Musicians" wherein the players in a civic orchestra discover that it their politics, not their performance, that will win them new instruments.

I would characterize Géza Csáth as "Poe + Freud," as his macabre, drug-fueled visions are informed by a professional's knowledge and clinical experience with mental illness. His writings also reflect the final convulsions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a dream world of sorts itself. These are not great stories, but many are quite good and would appeal to anyone with an interest in the literature of the period or of drug addiction.

Opium and Other Stories by Géza Csáth

Stories written in Hungarian 1908 to 1912

English translation by Jascha Kessler and Charlotte Rogers 1980

Géza Csáth, born 1887, was an upper middle class Hungarian who showed considerable talent as an artist, writer, musician and composer before deciding of his own volition to enter medical school. He devoted his early career to researching the origins of mental disorders, a fascination which carries over to the short stories he was writing at the time. At the same time, however, Csáth became addicted to opium. During the First World War he began his own descent into insanity. In 1919 he killed his wife, was institutionalized, escaped, and then killed himself.

Csáth's short stories are a mixture of the tragic, the absurd, the macabre and the fantastic. The author's mother died when he was a young child, leading evidently to a sense of betrayal that caused him to depict mothers as uncaring. Children are often the principal subjects of his stories, and they are typically angry and sadistic, wreaking violence and death on their pets, their siblings, and especially their mothers. In other stories young men are tantalized with the prospect of sexual pleasures, only to be thwarted by indifferent females, by their own inhibitions, or by waking at the wrong moment to find it was all a dream.

Csáth is not entirely misogynistic, however. In "Festal Slaughter" he presents a remarkably sensitive portrait of a servant girl who must rise in the freezing dawn to prepare for the slaughter of a sow by a visiting butcher. Along with her employer's family she works to exhaustion that day processing the carcass, making sausages, etc., only to be casually raped by the butcher before he leaves. She is just as much a piece of meat to her culture as the sow.

In the title story, "Opium," Csáth praises his favorite drug. Sure it shortens your life, he argues, but it slows time and extends the pleasures of each day. You may live, at most, for ten years, but in those ten years you will experience twenty million years of bliss before letting "your head fall on the icy pillow of eternal annihilation." Other stories present perhaps a more cautionary picture of addiction, such as one in which the narrator is plagued by dreams of a giant, fearsome toad in his kitchen.

There is a bit of black comedy in the collection as well, such as in the story "Father, Son" where a young man returns to Hungary from America to retrieve his father's skeleton from a medical college where it has just been put on display in a classroom. There is social satire too, such as the story "Musicians" wherein the players in a civic orchestra discover that it their politics, not their performance, that will win them new instruments.

I would characterize Géza Csáth as "Poe + Freud," as his macabre, drug-fueled visions are informed by a professional's knowledge and clinical experience with mental illness. His writings also reflect the final convulsions of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a dream world of sorts itself. These are not great stories, but many are quite good and would appeal to anyone with an interest in the literature of the period or of drug addiction.

26StevenTX

HUNGARY

Out of Oneself by András Pályi

Two novellas published in Hungarian in 1996 and 2001

English translation by Imre Goldstein 2005

Out of Oneself is a collection that consists of a pair of novellas that explore erotic desire as a force that is both redemptive and destructive.

"Beyond," the first piece, begins with a priest describing his own funeral. He has killed himself but is being given a church funeral because the provost (his uncle) managed to have him declared insane. Now he is a specter not only looking back on the events that led to his demise, but in some strange way reliving them, even making different choices, but seeing them lead over and over to the same end.

His story begins in 1936 when he has just celebrated his first mass and was approached by a beautiful young actress. In private the woman tells him about being troubled by memories of her childhood, but it is obvious that she is strongly attracted to him. He can't deny that the attraction is mutual, and before long they are having an affair. The priest can't find it in himself to believe that their love is wrong, yet each time he relives it, the end is the same. In his mind this endless destruction and resurrection takes on religious symbolism.

The second story, titled "At the End of the World," is set in Budapest in the 1980s. The principal female character is, again, an actress. On the set of a movie she finds herself attracted to the screenwriter. They are both still in their teens, and they have both left the homes of their foster or step-parents feeling as though they were cast out alone and in the rain. The girl has further anxieties from having been sexually molested by her stepfather since she was a small child.

Their attraction for each other is immediately and intensely physical. "Love is like God, we create it and believe in it. The pure moment is something else. Screaming, fear, pleasure, abandon." But the passion which redeems them from their sense of abandonment turns quickly into something they cannot control. "They had gone from slavery to freedom and then back to slavery. How could that have happened?"

The two stories both explore sexual psychology, but with their repetitive cycles of passion and despair they may also be historical allegories as well. The first instance depicting fascism with its antisemitism, the second communism with its class conflict. The male protagonist in each novella has his own prejudices to blame, in part, for his fate.

Earlier authors such as Georges Bataille have explored the linkage between eroticism, death and religion. These novellas are much in the same vein, and Out of Oneself will appeal to anyone who has enjoyed Bataille's work.

Out of Oneself by András Pályi

Two novellas published in Hungarian in 1996 and 2001

English translation by Imre Goldstein 2005

Out of Oneself is a collection that consists of a pair of novellas that explore erotic desire as a force that is both redemptive and destructive.

"Beyond," the first piece, begins with a priest describing his own funeral. He has killed himself but is being given a church funeral because the provost (his uncle) managed to have him declared insane. Now he is a specter not only looking back on the events that led to his demise, but in some strange way reliving them, even making different choices, but seeing them lead over and over to the same end.

His story begins in 1936 when he has just celebrated his first mass and was approached by a beautiful young actress. In private the woman tells him about being troubled by memories of her childhood, but it is obvious that she is strongly attracted to him. He can't deny that the attraction is mutual, and before long they are having an affair. The priest can't find it in himself to believe that their love is wrong, yet each time he relives it, the end is the same. In his mind this endless destruction and resurrection takes on religious symbolism.

The second story, titled "At the End of the World," is set in Budapest in the 1980s. The principal female character is, again, an actress. On the set of a movie she finds herself attracted to the screenwriter. They are both still in their teens, and they have both left the homes of their foster or step-parents feeling as though they were cast out alone and in the rain. The girl has further anxieties from having been sexually molested by her stepfather since she was a small child.

Their attraction for each other is immediately and intensely physical. "Love is like God, we create it and believe in it. The pure moment is something else. Screaming, fear, pleasure, abandon." But the passion which redeems them from their sense of abandonment turns quickly into something they cannot control. "They had gone from slavery to freedom and then back to slavery. How could that have happened?"

The two stories both explore sexual psychology, but with their repetitive cycles of passion and despair they may also be historical allegories as well. The first instance depicting fascism with its antisemitism, the second communism with its class conflict. The male protagonist in each novella has his own prejudices to blame, in part, for his fate.

Earlier authors such as Georges Bataille have explored the linkage between eroticism, death and religion. These novellas are much in the same vein, and Out of Oneself will appeal to anyone who has enjoyed Bataille's work.

27labfs39

3. This Way for the Gas, Ladies and Gentlemen by Tadeusz Borowski

To understand these stories, I think it helps to understand the author's background. Tadeusz Borowski was born in the Soviet Ukraine to Polish parents. As a child, his father was interred in one of the harshest Soviet labor camps, above the Arctic Circle, digging the White Sea Canal. When Borowski was eight, his mother was sent to work in Siberia as well. He lived with an aunt until his family was repatriated to Warsaw in the early 1930s. In 1943, Borowski and his fiance were arrested for their participation in underground publications and sent to Auschwitz. Although both survived the camps and later married, Borowski was unable to reconcile his desire to write the truth with the demands of the communist State on authors. At the age of 29, he turned on the gas in his apartment and committed suicide.

This collection of twelve short stories are inspired by the author's experiences in Auschwitz and Dachau. The first two stories were written and published in Poland right after his release. "They produced a shock," writes Jan Kott in his introduction. "The public was expecting martyrologies; the Communist party called for works that were ideological, that divided the world into the righteous and the unrighteous, heroes and traitors, Communists and Fascists. Borowski was accused of amorality, decadence, and nihilism. Yet at the same time it was clear to everyone that Polish literature had gained a dazzling new talent." Borowski eschewed easy answers and wrote about the moral ambiguities that plagued him. He had survived the camps, but at what cost? Three of his stories are written from the perspective of a deputy Kapo, Vorarbeiter Tadeusz. Young, impressionable, and wanting to survive, Vorarbeiter Tadeusz has a minor position over other prisoners that gives him perks of food and clothes which allow him to survive, but at the cost of moral clarity. Small compromises become everyday, violence and lack of compassion become less uncomfortable, and he survives. But some horrors still have the power to shock, which allows Tadeusz to maintain his humanity.

The stories are horrible to read not only because of the situation, but precisely because there are no heroes, and everyone is both a perpetrator and a victim. Borowski learned this first hand in the camps and lived it afterwards in Communist Poland. The moral ambiguity of his position is, perhaps, what caused him to commit suicide. I found this collection extremely depressing, even more so than other Holocaust literature, and challenging in its unflinching look at the dark side of survival.

28rebeccanyc

HUNGARY

Kornél Esti by Dezsõ Kosztolányi

Published 1933; English translation 2011

This book grew on me as I read it. In the first chapter, the unnamed narrator decides to visit his estranged childhood friend Kornél Esti, a fellow writer and indeed an alter ego who looks exactly like him and who encouraged him in all his pranks and bad boy activities as a child and young man. He finds Esti somewhat down on his luck and suggests that they "stick together" from that point onwards and collaborate in writing a book about Esti's exploits. After some discussion of how this will work and whose name will be bigger on the cover, they agree that Esti will tell stories of his life to the narrator, stories that may or may not be true, and the narrator will "edit" them slightly.

The rest of the book takes off from there in a series of episodic chapters, more or less in chronological order. Some of Esti's stories border on the realistic, others are fantastic or metaphorical or whimsical or disturbing -- or a mixture of all of these, and Esti does not always present himself as an admirable person. Written in the early 1930s, itself a time of growing turmoil, the book takes place both before and after the first world war, the war which finally toppled the Austro-Hungarian empire and resulted in the loss of a significant portion of what had been Hungary to neighboring countries. Never alluded to directly, this is nonetheless a dividing line in Hungarian history and in Hungarian self-perception.

Many of the stories are delightful (although always thought-provoking) -- for example, there is a story about a town in which everyone always tells the truth (so that a restaurant might advertize "Inedible food, undrinkable drinks"); one about a magnificent hotel with hundreds of staff members, each of whom resembles (or is) a famous person such as Thomas Edison, Rodin, and Marie Antoinette; one in which he struggles to get rid of an inheritance; one in which a friend who says he will only stay for a few minutes ends up staying for hours; and one in which he carries on a conversation with a Bulgarian train conductor although he speaks not a word of the language. Others depict life in the literary cafes of Budapest, or the attitudes of peasants, or encounters on trains. Still others are more grim in their portrayal of people with mental illness or in dire financial straits. One of my favorite chapters is the one in which Esti describes his time as a student in Germany; his understated satire of German behavior is priceless, and perhaps a little pointed in 1933. The book ends with Esti boarding a tram that is both real and metaphorical for an unnamed destination that turns out to be the "Terminus."

All in all, I enjoyed this book a lot. Unlike the only other book by Kosztolányi which I've read, Skylark, it does not tell a straightforward story but is quite modern in its almost metafictional style. I also enjoyed Kosztolányi's (or Esti's) technique of occasionally mixing story-telling with philosophical thoughts, while providing a fanciful yet serious picture of a world which was already slipping away when he wrote.

Kornél Esti by Dezsõ Kosztolányi

Published 1933; English translation 2011

This book grew on me as I read it. In the first chapter, the unnamed narrator decides to visit his estranged childhood friend Kornél Esti, a fellow writer and indeed an alter ego who looks exactly like him and who encouraged him in all his pranks and bad boy activities as a child and young man. He finds Esti somewhat down on his luck and suggests that they "stick together" from that point onwards and collaborate in writing a book about Esti's exploits. After some discussion of how this will work and whose name will be bigger on the cover, they agree that Esti will tell stories of his life to the narrator, stories that may or may not be true, and the narrator will "edit" them slightly.

The rest of the book takes off from there in a series of episodic chapters, more or less in chronological order. Some of Esti's stories border on the realistic, others are fantastic or metaphorical or whimsical or disturbing -- or a mixture of all of these, and Esti does not always present himself as an admirable person. Written in the early 1930s, itself a time of growing turmoil, the book takes place both before and after the first world war, the war which finally toppled the Austro-Hungarian empire and resulted in the loss of a significant portion of what had been Hungary to neighboring countries. Never alluded to directly, this is nonetheless a dividing line in Hungarian history and in Hungarian self-perception.