Folio Archives 213: The Life of Charlemagne by Einhard 1970

ConversazioniFolio Society Devotees

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

1wcarter

The Life of Charlemagne by Einhard the Frank 1970

It is not often that you are able to read a book that was written 1200 years ago, and written about a famous figure by one of his contemporaries. Charlemagne inherited a kingdom from his father, and more later from the premature death of his brother, that encompassed most of modern day France and Switzerland, as well as western Germany and Benelux. By the time of his death his empire stretched from Brittany to Rome, and from Pamplona in NE Spain to Hamburg and Budapest. Many of the states further East in Europe were vassals.

Einhard the Frank was one of Charlemagne’s advisors, and an intimate member of his court. All we know about him was written in the original forward to the book, and there we learn that his most notable feature was that he was remarkably short, but not a dwarf, so about 150cm. (4ft. 8in.) tall. This brief book was written at some time between 829 and 836, some years after the death of Charlemagne in 814.

Einhard divides his book, which takes only 6o pages of this volume, into separate chapters about Charlemagne’s ancestors, his wars and political intrigues, his private life, his death and his heirs. His facts are sometimes confused, and the modern editor has corrected these errors in the texts.

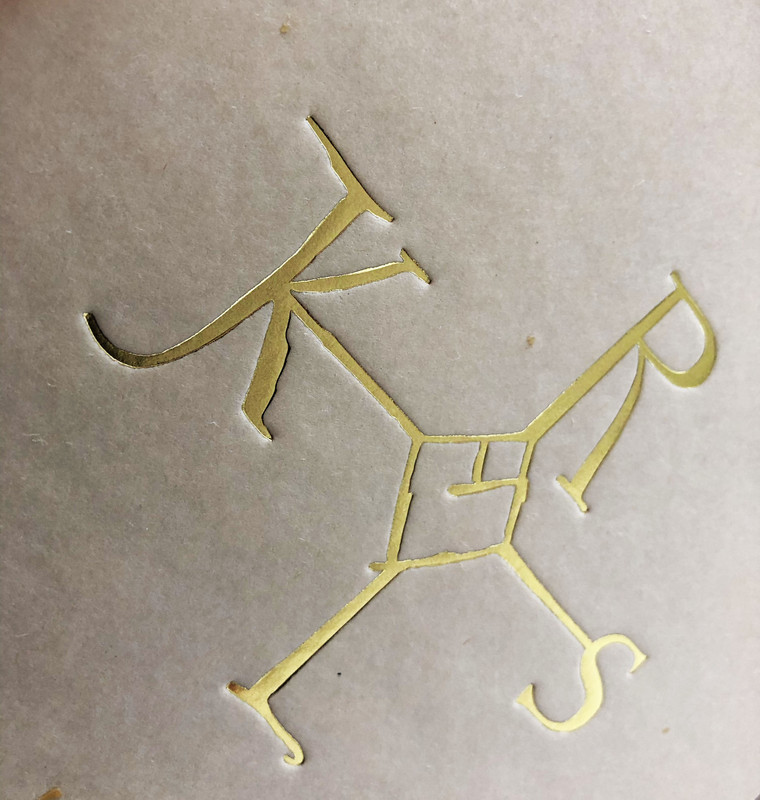

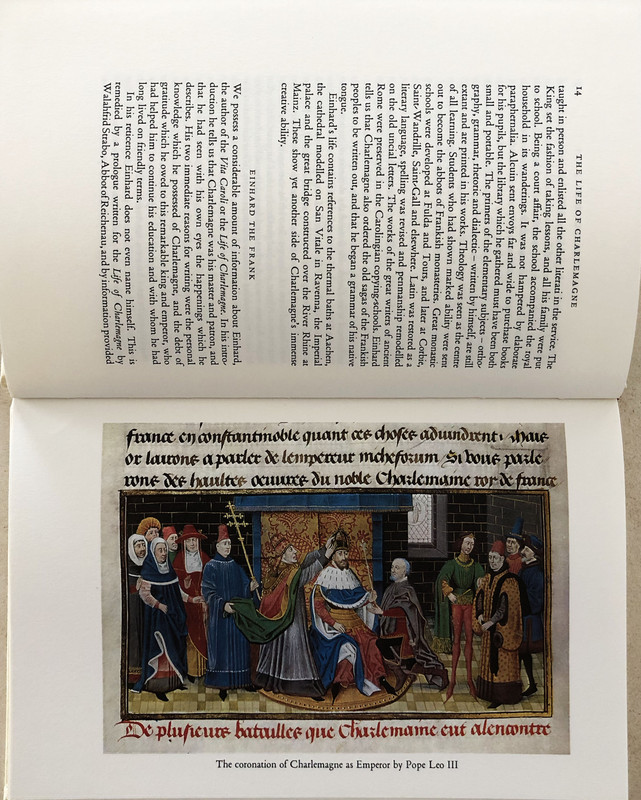

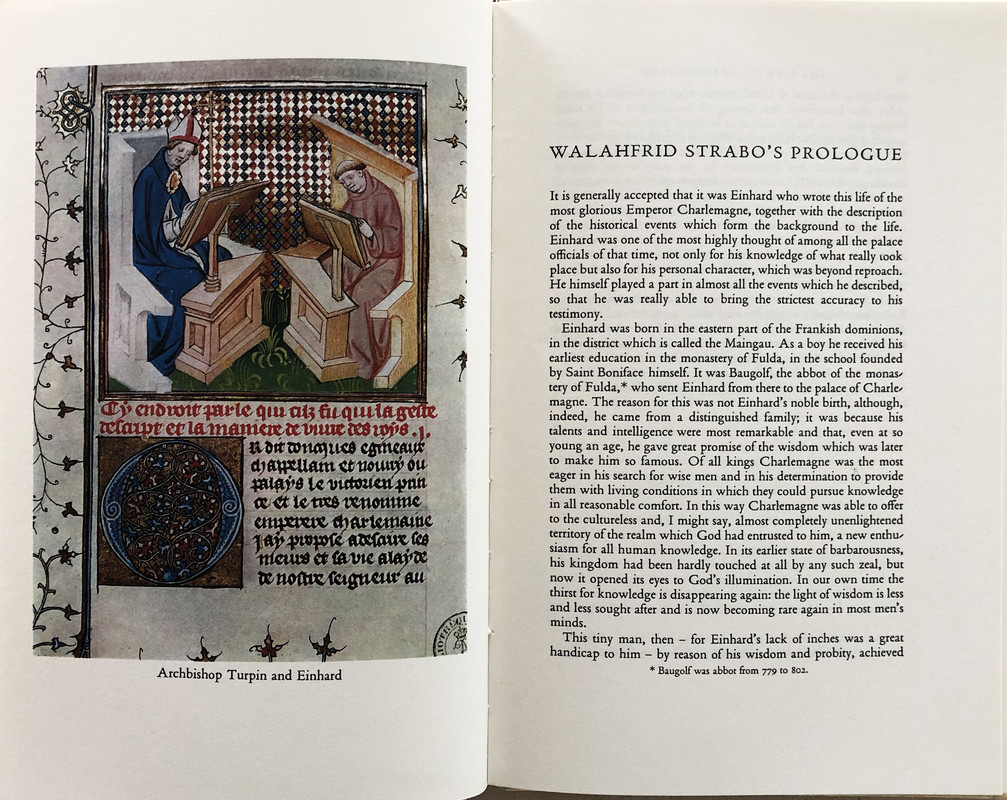

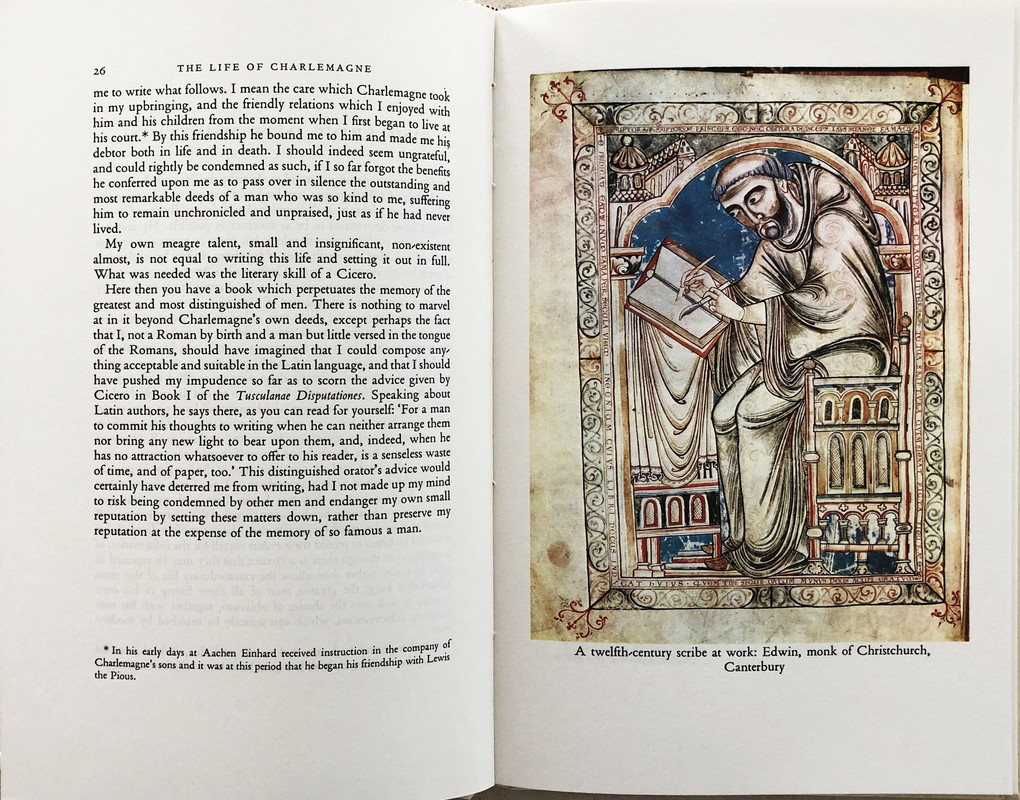

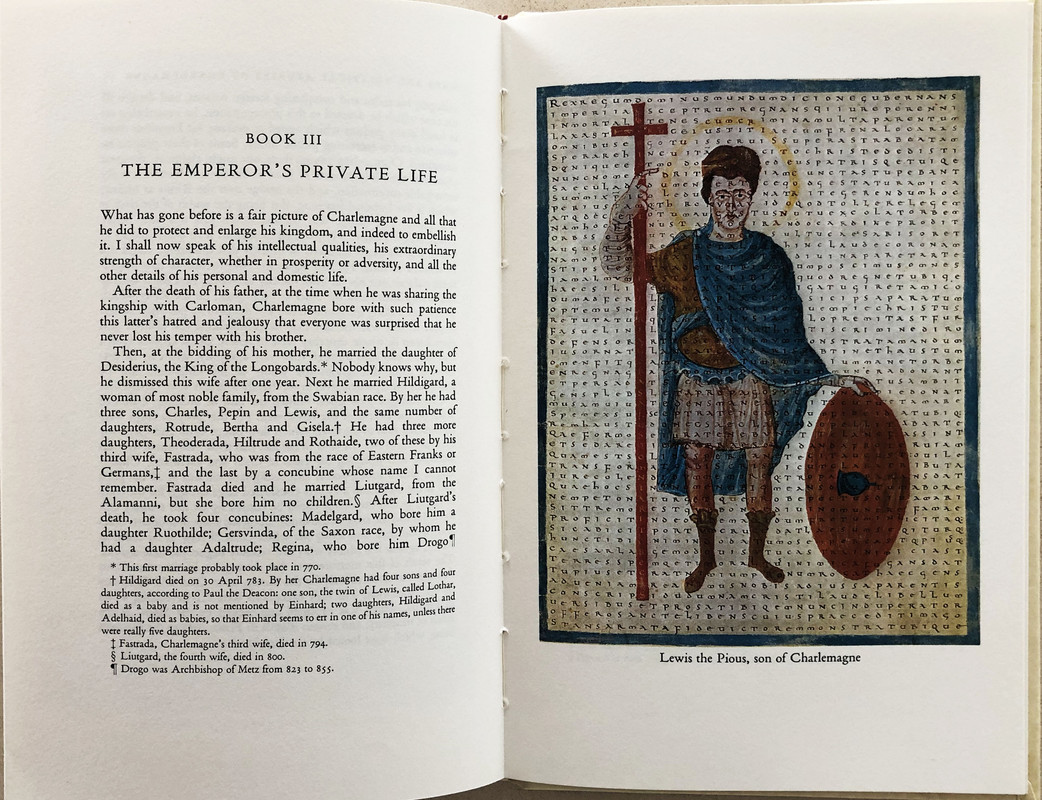

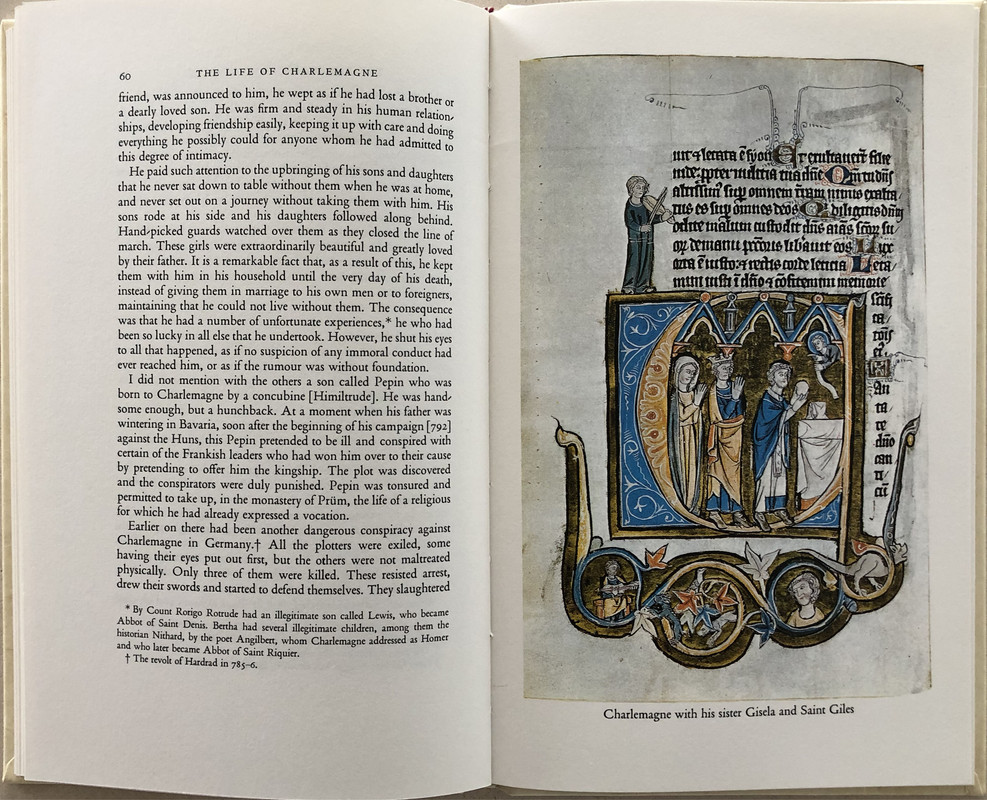

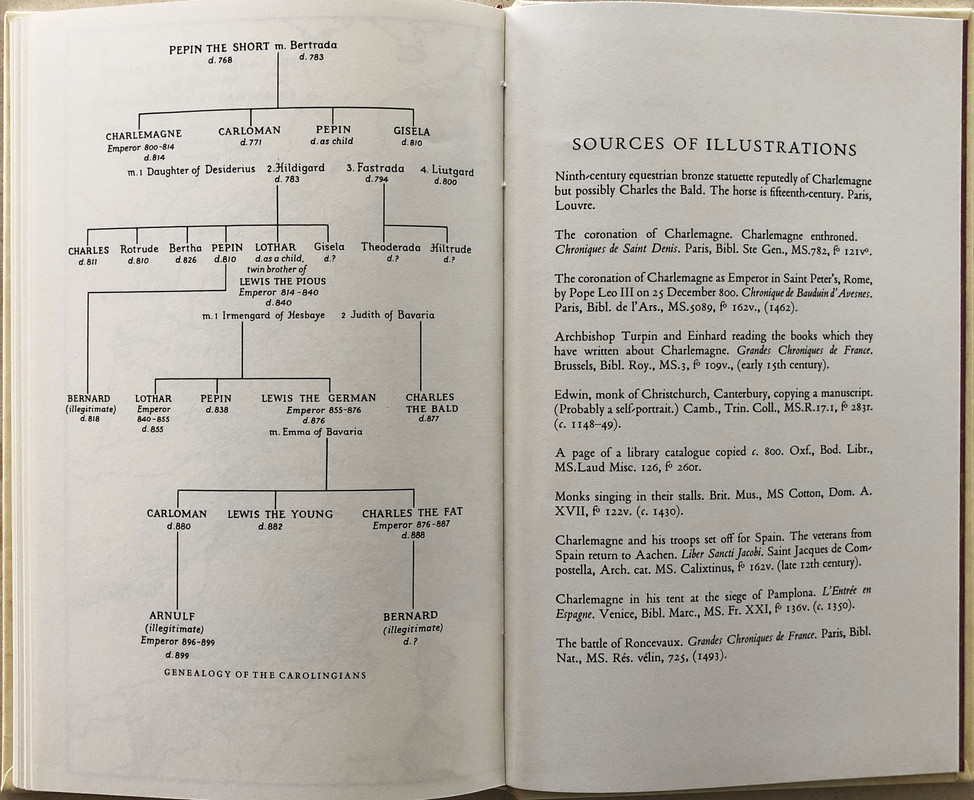

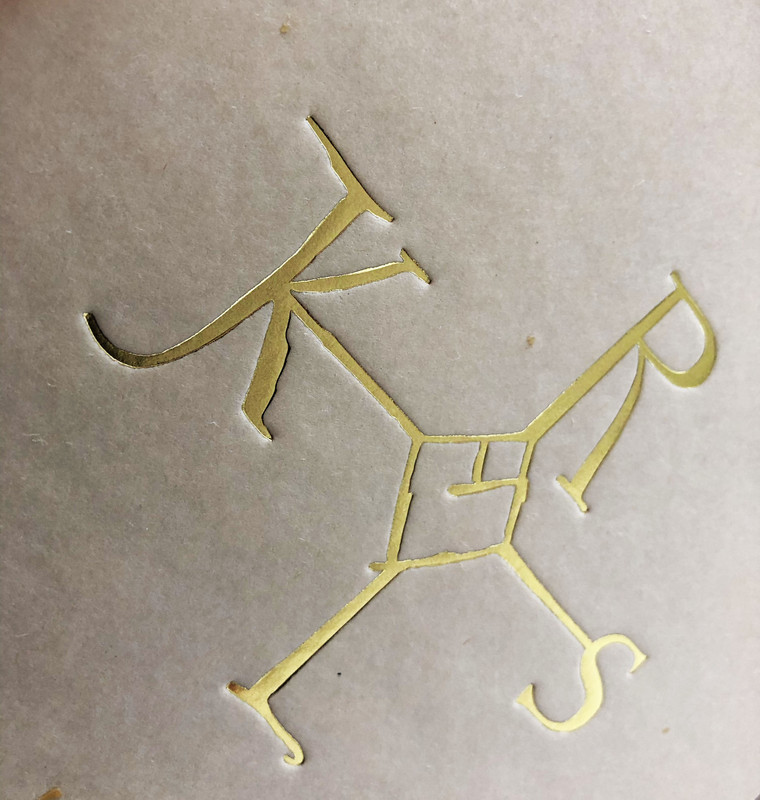

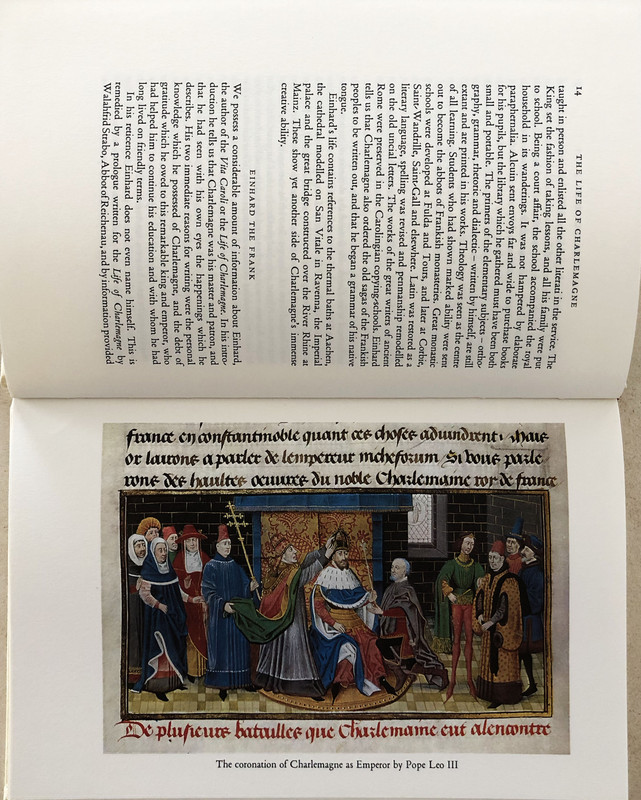

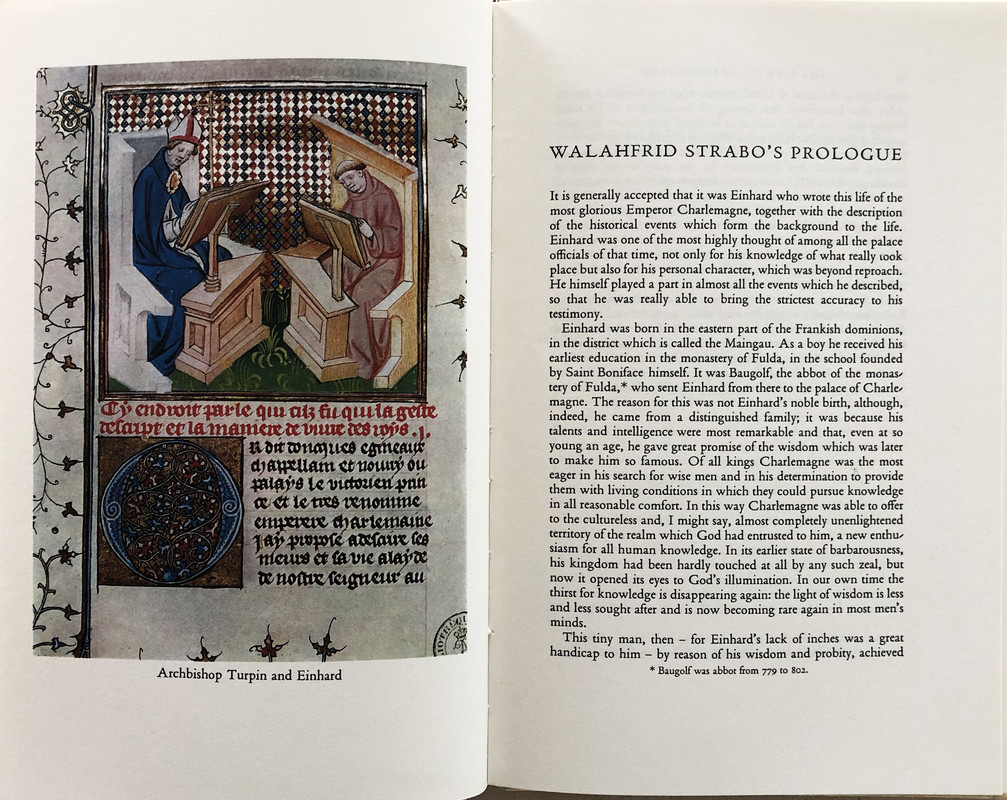

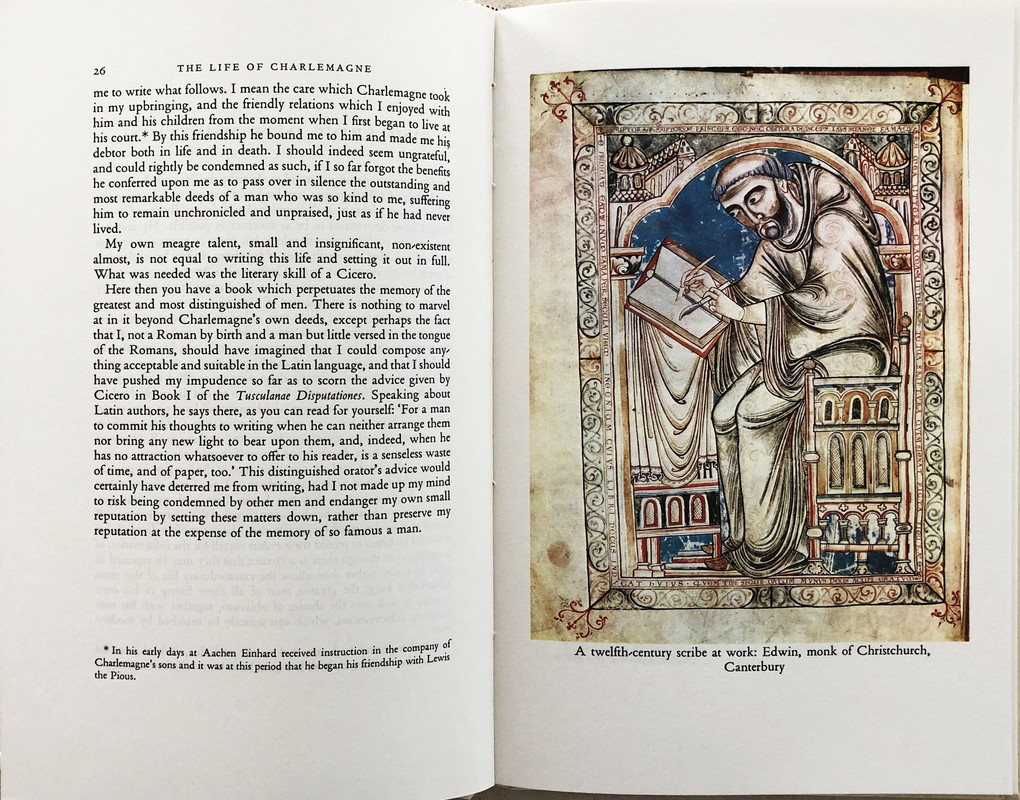

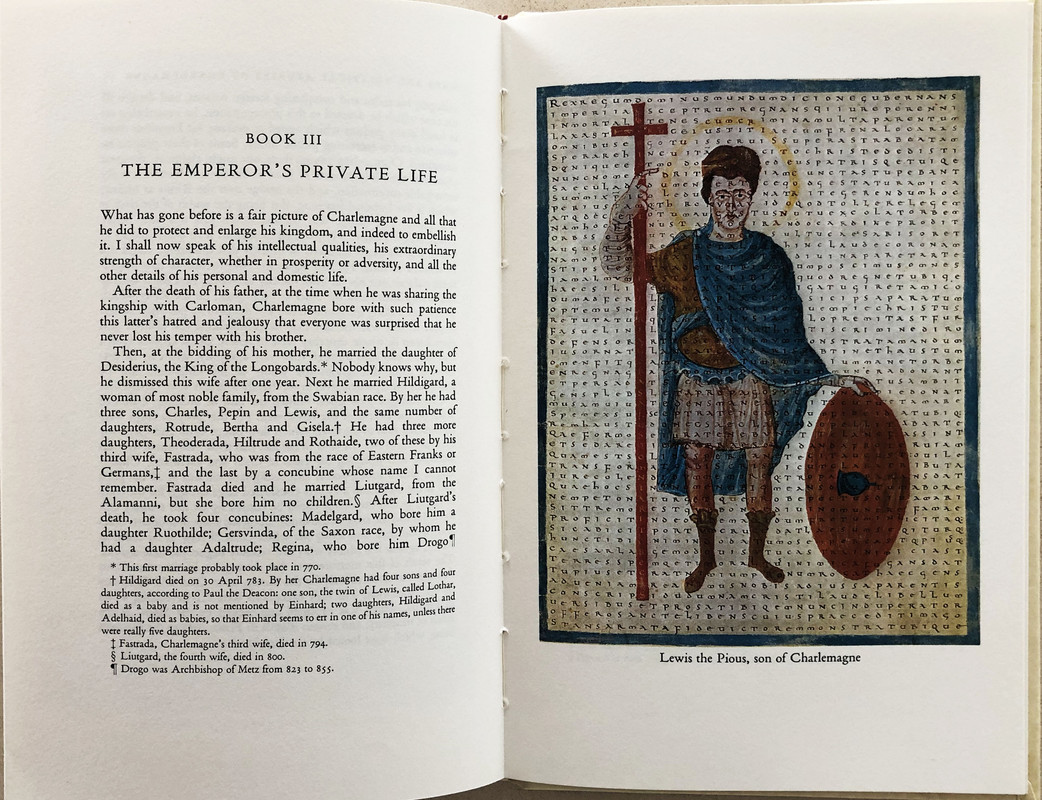

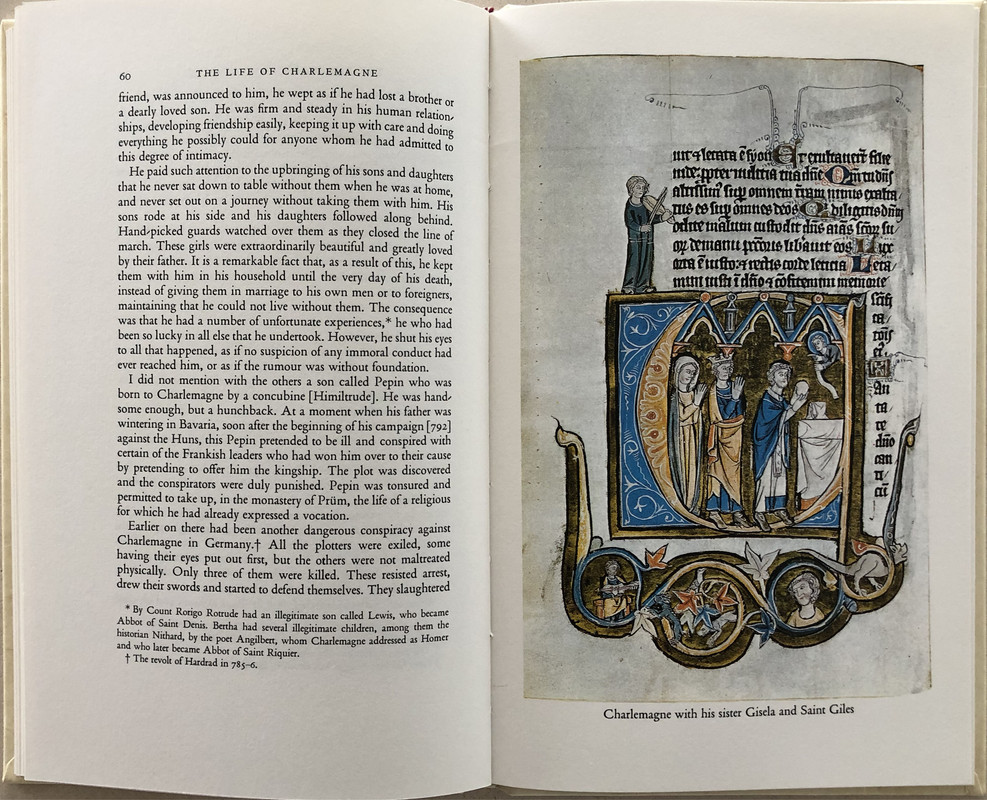

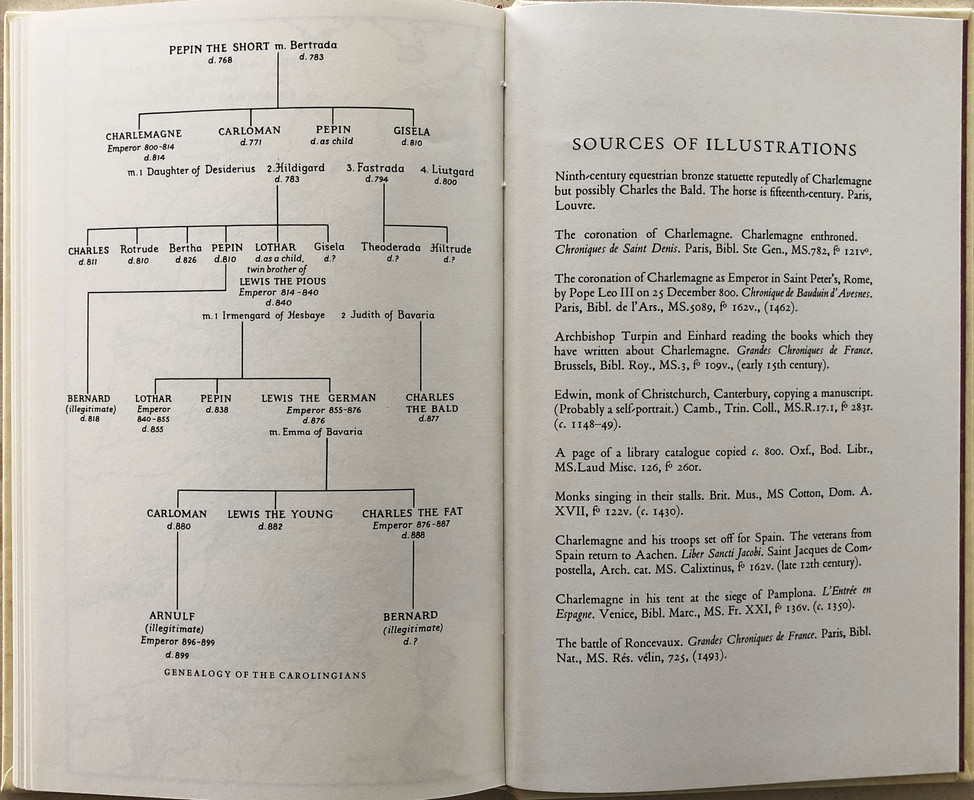

The entire book has only 88 pages plus a very generous 17 bound-in colour plates of 9th. century paintings and artefacts. It is translated and introduced by Lewis Thorpe, and there is a genealogical table and map at the back of the book. The endpapers are maroon and printed with a gilt design representing Charlemagne’s signature.

The book is bound in full cream vegetable parchment, cover blocked and indented with a gold cypher. The gilt spine title runs from bottom to top. The slipcase is purple (mine has edge fading) and 26.2x16.4cm. This was the presentation volume (given free to members who ordered four or more books) for 1970.

Endpapers

An index of the other illustrated reviews in the "Folio Archives" series can be viewed here.

It is not often that you are able to read a book that was written 1200 years ago, and written about a famous figure by one of his contemporaries. Charlemagne inherited a kingdom from his father, and more later from the premature death of his brother, that encompassed most of modern day France and Switzerland, as well as western Germany and Benelux. By the time of his death his empire stretched from Brittany to Rome, and from Pamplona in NE Spain to Hamburg and Budapest. Many of the states further East in Europe were vassals.

Einhard the Frank was one of Charlemagne’s advisors, and an intimate member of his court. All we know about him was written in the original forward to the book, and there we learn that his most notable feature was that he was remarkably short, but not a dwarf, so about 150cm. (4ft. 8in.) tall. This brief book was written at some time between 829 and 836, some years after the death of Charlemagne in 814.

Einhard divides his book, which takes only 6o pages of this volume, into separate chapters about Charlemagne’s ancestors, his wars and political intrigues, his private life, his death and his heirs. His facts are sometimes confused, and the modern editor has corrected these errors in the texts.

The entire book has only 88 pages plus a very generous 17 bound-in colour plates of 9th. century paintings and artefacts. It is translated and introduced by Lewis Thorpe, and there is a genealogical table and map at the back of the book. The endpapers are maroon and printed with a gilt design representing Charlemagne’s signature.

The book is bound in full cream vegetable parchment, cover blocked and indented with a gold cypher. The gilt spine title runs from bottom to top. The slipcase is purple (mine has edge fading) and 26.2x16.4cm. This was the presentation volume (given free to members who ordered four or more books) for 1970.

Endpapers

An index of the other illustrated reviews in the "Folio Archives" series can be viewed here.

2Sorion

Thanks for this >1 wcarter: . This is one I will be keeping an eye out for, it needs to be in my collection.

3elladan0891

This is one of the books I'm reading right now. I would also add that the paper is nice - textured and very thick. The translation is very easy to read, and Einhard's language (at least in this translation) is very straight-forward. Translator's introduction is fairly short and can be read before plunging into the work itself. And the way the actual work is set up seems surprisingly modern - it has an author's preface, and even a 2-page foreword by a literary figure contemporary to work's original "publication"! Didn't expect that from a 9th century book.

Also, objectivity of Einhard and other Carolingian authors is often put to question, even in the book's introduction, them being in Charlemagne's service and all; but Einhard actually strikes me as very reasonable in his approach, particularly for the times. For example, he states in the beginning that he won't be writing anything about birth or childhood of Charlemagne since he wasn't there to witness it and doesn't know anyone else who did. And I'm about 3/4 in, but so far I don't see any excessive glorifying of the patron either.

Translator's notes are done as footnotes, not endnotes, which is great, and are short and not too numerous so don't become interruptive.

The one criticism I do have is that a few of these notes, particularly those meant to correct Einhard's presumed mistakes, seem odd. For example, when Einhard talks about letters from the king of Asturias Alphonso II to Charlemagne, the translator makes a short puzzling note that "no such letters exist" without any explanation or elaboration. Is he trying to say that if the letters are not known to exist now it means they never existed? Because every single letter written 1200 years ago survived to present days, is accounted for, and it's unthinkable to suggest otherwise? Or is it because he sees some inconsistencies that suggest that such letters could not have existed? Well, explain the inconsistencies, then.

All in all - a very quick and easy read in a nice and satisfying edition recommended for all interested in such things.

Also, objectivity of Einhard and other Carolingian authors is often put to question, even in the book's introduction, them being in Charlemagne's service and all; but Einhard actually strikes me as very reasonable in his approach, particularly for the times. For example, he states in the beginning that he won't be writing anything about birth or childhood of Charlemagne since he wasn't there to witness it and doesn't know anyone else who did. And I'm about 3/4 in, but so far I don't see any excessive glorifying of the patron either.

Translator's notes are done as footnotes, not endnotes, which is great, and are short and not too numerous so don't become interruptive.

The one criticism I do have is that a few of these notes, particularly those meant to correct Einhard's presumed mistakes, seem odd. For example, when Einhard talks about letters from the king of Asturias Alphonso II to Charlemagne, the translator makes a short puzzling note that "no such letters exist" without any explanation or elaboration. Is he trying to say that if the letters are not known to exist now it means they never existed? Because every single letter written 1200 years ago survived to present days, is accounted for, and it's unthinkable to suggest otherwise? Or is it because he sees some inconsistencies that suggest that such letters could not have existed? Well, explain the inconsistencies, then.

All in all - a very quick and easy read in a nice and satisfying edition recommended for all interested in such things.