Baswood's books

Questa conversazione è stata continuata da Baswood's books - well - part 2.

ConversazioniClub Read 2021

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

1baswood

Last year I read 100 books and largely kept to my reading programme that I worked out at the start of the year. 100 books is the most I have ever recorded since I have used LT and so I figured that this years target should be the same and so over the last week I have selected my books for the year; any more will be a bonus.

The topics will be the same as last year and so:

Elizabethan literature

I am reading through on a year by year basis and I am now at 1594 (precise dates of publications or manuscripts are subject to much debate by literary scholars). The plague was raging in London and so the theatres were closed and so much of the material available is poetry or pamphlets and so I will start with two sonnet cycles by Thomas Lodge and Giles Fletcher and then move on to Shakespeare's poetry. Towards the end of my reading year I plan to get to four more of Shakespeares plays:

Loves Labours Lost

King John

Richard II

A Midsummer Nights dream

In between there will be works by Thomas Nashe Edmund Spenser Michael Drayton George Chapman Henry Wilobie and others.

Last year I picked a year at random 1951 withy the aim of reading as many books as I could published that year and found that I made many excellent discoveries which included:

Bestiary, Julio Cortazar

Jean Giono - Le Hussard sur le toit

A. M Klein - The second scroll

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

Morley Callaghan - The loved and the Lost

Howard Fast - Spartacus

Rachel Carson - The Sea around us

Shirley Jackson - Hangsaman

The Conformist - Alberto Moravia

The Grass Harp - Truman Capote

My Cousin Rachel Daphne DuMaurier

From Here to Eternity James Jones

The Cruel Sea Nicholas Monsarrat

and books by Ngaio Marsh Hammond Innes John Dickson Carr Olivia Manning John Masters Nancy Mitford

I am therefore going to carry on with 1951 as there are still some goodies to come:

A dance to the music of time Anthony Powell

Cairo to Damascus John Roy Carlson

Fires on the Plain Shoei Ooka

The log from the Sea of Cortez John Steinbeck

Curtains for Three Rex Stout

Lie down in darkness William Styron

A Game of Hide and Seek Elizabeth Taylor

The Goshawk T H White

The Cain Mutiny Herman Wouk

Judgement at Deltchev Eric Ambler

Seven Summers Milk Raj Anand

Colonel Julian and other stories H E Bates

Look down in Mercy Walter Baxter

Early stories, Elizabeth Bowen

Fancies and Goodnights John Collier

Marianne Rhys Davies

Conscience of the king Alfred Duggan

Pigeons in the Grass Wolfgang Koeppen

This man and this Woman James T Farrel

Chicago city on the Make Nelson Algren

Complete Clerihews E Clerihew Bently

Two cheers for democracy E M Forster

Poetry and drama T S Eliot

The End of the Affair Graham Green

The West Pier Patrick Hamilton

Le Rivage de Syrtes Julian Gracq

Memoires D'Hadrian Marguerite Yourcenar

Catcher in the Rye

There are at least another 150 books to read from that year, which are still available.

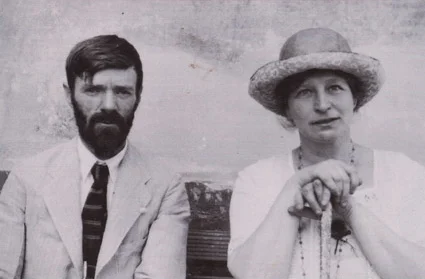

I am still aiming to complete the unread books on my shelves whose authors names begin with the letter B I have 15 of them including two by Balzac which I will try and read in French. I also have three books in the series The complete letters of D H Lawrence and books that are not on my shelves yet, but I hope to read this year are the Four seasons Quartet by Ali Smith

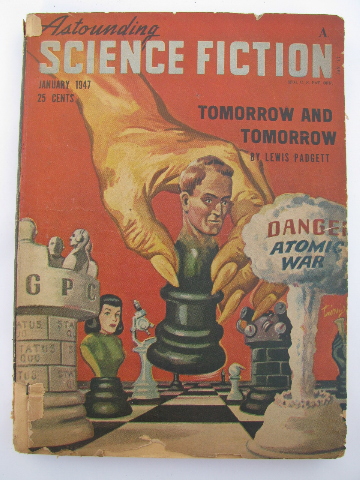

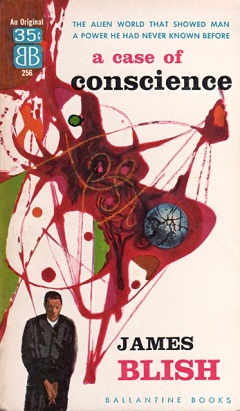

Science Fiction reading will continue with books from the 1950's

My reading will entail buying a lot more books (hooray), but I have only selected books that will cost less than 20 euros, many of the older books are of course free on the net.

The topics will be the same as last year and so:

Elizabethan literature

I am reading through on a year by year basis and I am now at 1594 (precise dates of publications or manuscripts are subject to much debate by literary scholars). The plague was raging in London and so the theatres were closed and so much of the material available is poetry or pamphlets and so I will start with two sonnet cycles by Thomas Lodge and Giles Fletcher and then move on to Shakespeare's poetry. Towards the end of my reading year I plan to get to four more of Shakespeares plays:

Loves Labours Lost

King John

Richard II

A Midsummer Nights dream

In between there will be works by Thomas Nashe Edmund Spenser Michael Drayton George Chapman Henry Wilobie and others.

Last year I picked a year at random 1951 withy the aim of reading as many books as I could published that year and found that I made many excellent discoveries which included:

Bestiary, Julio Cortazar

Jean Giono - Le Hussard sur le toit

A. M Klein - The second scroll

Simone de Beauvoir - The Mandarins

Morley Callaghan - The loved and the Lost

Howard Fast - Spartacus

Rachel Carson - The Sea around us

Shirley Jackson - Hangsaman

The Conformist - Alberto Moravia

The Grass Harp - Truman Capote

My Cousin Rachel Daphne DuMaurier

From Here to Eternity James Jones

The Cruel Sea Nicholas Monsarrat

and books by Ngaio Marsh Hammond Innes John Dickson Carr Olivia Manning John Masters Nancy Mitford

I am therefore going to carry on with 1951 as there are still some goodies to come:

A dance to the music of time Anthony Powell

Cairo to Damascus John Roy Carlson

Fires on the Plain Shoei Ooka

The log from the Sea of Cortez John Steinbeck

Curtains for Three Rex Stout

Lie down in darkness William Styron

A Game of Hide and Seek Elizabeth Taylor

The Goshawk T H White

The Cain Mutiny Herman Wouk

Judgement at Deltchev Eric Ambler

Seven Summers Milk Raj Anand

Colonel Julian and other stories H E Bates

Look down in Mercy Walter Baxter

Early stories, Elizabeth Bowen

Fancies and Goodnights John Collier

Marianne Rhys Davies

Conscience of the king Alfred Duggan

Pigeons in the Grass Wolfgang Koeppen

This man and this Woman James T Farrel

Chicago city on the Make Nelson Algren

Complete Clerihews E Clerihew Bently

Two cheers for democracy E M Forster

Poetry and drama T S Eliot

The End of the Affair Graham Green

The West Pier Patrick Hamilton

Le Rivage de Syrtes Julian Gracq

Memoires D'Hadrian Marguerite Yourcenar

Catcher in the Rye

There are at least another 150 books to read from that year, which are still available.

I am still aiming to complete the unread books on my shelves whose authors names begin with the letter B I have 15 of them including two by Balzac which I will try and read in French. I also have three books in the series The complete letters of D H Lawrence and books that are not on my shelves yet, but I hope to read this year are the Four seasons Quartet by Ali Smith

Science Fiction reading will continue with books from the 1950's

My reading will entail buying a lot more books (hooray), but I have only selected books that will cost less than 20 euros, many of the older books are of course free on the net.

2AnnieMod

Between your Elizabethan reading and the classic SF, I always find interesting things on your threads. So I am just going to grab a coffee and sit down in the corner :)

Happy new year, Barry!

Happy new year, Barry!

4OscarWilde87

Happy New Year, Bas! I will be following again, as always. Looking forward to your thoughts on the Steinbeck. I haven't read The log from the Sea of Cortez yet, but it is on my list.

5baswood

Nones - W. H. Auden

When this collection of poetry was published in 1951, many people considered Auden to be the greatest living poet, however some would claim that his best poetry was behind him and that he had to some extent lost his voice when war was declared in 1939. I am no expert on Auden's poetry only dipping in to various poems in anthologies and such like. My impression is that Auden is a poet of many faces for example some poems can be almost childlike in their simplicity and rhyming patterns with a sing-song like quality, while others can be wilfully obscure with no discernible structure and almost everything else in between. What is palpably obvious was that Auden was always in control of his technical ability and if the poems were open to interpretation then that was part of the process. I was excited then to read a collection of his later poems that he had put together for publication.

The collection starts with an introductory poem seemingly a dedication and entitled "To Reinhold and Ursula Niebuhr" The Niebuhr's were academics and theologians and were in correspondence with Auden over a number of years and especially at a time when Auden had returned to Christianity. They were also like Auden making a new life for themselves in America. The poem starts with the line;

"We, too, had known golden hours,"

and ends with the quatrain

"And where should we find shelter

For joy or mere content

When little was left standing

But the suburbs of dissent."

Auden knew that some of his devotees and critics were after him, but in this collection he seems not to care, producing a few of the more simple nursery type poems along with those where a dictionary of obscure/antiquated words would be helpful. What is evident is that many of the poems have a religious quality about them, a basic christian believe in God. This rarely becomes so overt that it feels like preaching, but many of the poems have this belief at their heart.

It would seem that most of the poems had been written during the period 1948-51 and so the big event in many people lives was a readjustment after the end of the second world war and Auden whatever one could accuse him of was never a poet to cocoon himself from current events and so this collection of a moment in time reflects the poets thought and fears for humanity first, and himself second. There are some wonderful poems in this collection there are also some that I don't pretend to understand and others that I just don't like, but most have that technical quality that makes them a joy to read. What is typical of the poet for me is that a poem will open with an idea that stimulates my imagination and then as it goes on I find myself getting lost as where it is going, stopping to think is an absolute requirement in a poem like "In Praise of Limestone" which seems to have a theme of the loss of innocence. I love some of the individual lines, but cannot always see the connection. I found myself looking at an analysis of the poem by other readers on the internet and discovered that they were as clueless as me. There is so much packed into those lines that an overall understanding is difficult and left me with the conclusion that I would probably read the poem differently every time I re-read it. Perhaps not a bad thing.

There were plenty of poems that I really enjoyed "Not in Baedeker" where the speaker reminisces about a town that was once the centre for a huge lead mine, but now after a relatively few decades the only evidence of the mine itself is in the contours of the landscape. It is an ugly looking poem but spoke to me because I lived for a time in an old lead mining village. "Ischia" is a homage to Southern Italy and the pleasures for a visitor but Auden warns:

"Nothing is free, whatever your charge shall be paid

That these days of exotic splendour may stand out

In each lifetime like marble

Mileposts in an alluvial land"

"The fall of Rome' where each stanza is a vignette of the fall of civilization. The 'Managers' which muses on those sometime faceless people that have control over your destiny. 'A Household' where the "man" of the house believes his own lies. The 'Duet' is another of my favourite poems. The speaker contrasts a singer of classical music giving a recital in a warm rich household while outside in the cold winter a scrawny beggar is an organ grinder:

“But to her gale

Of sorrow from the moonstruck darkness

That ragged runagate opposed his spark”

The title poem "Nones" is one of the more difficult poems to come to grips with as a whole, but each stanza deals with an aspect of humanity's shortcomings and ends with the thought that although we can heal ourselves ; death is coming. The collection ends with two absolute crackers. "The Precious Five Senses" where Auden devotes a stanza each to Nose-smell, Ears-hearing, sight-seeing, tongue-women (oops), hands-touch and brings these all together in a final stanza. The poem is both witty and thought provoking in equal measure; here is the opening lines to the stanza on ears:

Be modest, lively ears,

Spoiled Darlings of the stage

Where any caper cheers

The paranoic mind

Of this undisciplined

And concert-going age,

So lacking in conviction

It cannot take pure fiction

And what it wants from you

Are rumours partly true`

A Walk after Dark the final poem sounds personal to me; readers of poetry are encouraged to think of a neutral speaker as the voice of the poem, but in this instance It is personal:

"Now, unready to die

But already at the stage

When one starts to dislike the young

I am glad those points in the sky

May also be counted among

The creatures of middle age."

The poet takes a walk and looks up at the stars and thinks about the state of the world, and his own place in it, but it ends with a note of uncertainty eased by his new friends in his adopted country:

"But the stars burn overhead,

Unconscious of final ends,

As I walk home to bed,

Asking what judgement waits

My person, all my friends,

And these United States."

Writing about and reliving some of these poems is surely what reading is all about. Another great publication from 1951 and a five star read

6kidzdoc

Great review of Nones, Barry. That seems like a book I would be interested in reading, although I suspect it would be difficult to find in the US.

7dchaikin

A great post to open the year. I was thinking how reading your 1951 reviews gives us a curious timeslice, but my thought process got lost thinking about these Auden poems. I haven’t read Auden.

8thorold

>5 baswood: A nice find! I’ve never got very far with late Auden, but I remember “Not in Baedeker” — it’s presumably Italy, but he makes it sound very like Derbyshire or the Lakes. Re-reading it, I somehow couldn’t help imagining Auden dressed in a Portillo blazer and wandering around book-in-hand followed by a camera team. But the pleasure he takes in the Victorian writer spelling “gulph” with a ph is so lovely!

9baswood

>8 thorold: yes I presume it was set in Italy. I lived for a while in Wensley Derbyshire which was home at one time to the largest lead mine in Europe. The poem just feels so East Midlands.

10raton-liseur

Happy new year baswood! There are interesting books in your 1951 list. I'll be happy to follow your reads and hope you'll have a wonderful literary year!

Out of curiosity, what are the two Balzac that you plan reading?

Out of curiosity, what are the two Balzac that you plan reading?

11AlisonY

Really interesting review on the Auden collection. I'll be learning plenty on your thread again this year.

13baswood

L'écume des Jours - Boris Vian

I have never read a book quite like L'écume des jours, but then again I have never read a book quite like Le Petit Prince by Antoine de Saint Exupery and so reading these two in parallel was quite a strange experience, because in some aspects they are similar. Le Petit Prince was published in 1943 and Boris Vian's first novel hit the streets in 1947, both scenario's take place in a sort of parallel universe and its easy to believe that Vian was thoroughly familiar with The Petit Prince when he wrote L'écume des jours which takes his parallel world out of the reach of children and into a world of tragedy and satire.

L'écume des Jours tells the story of Colin a wealthy young man who loves jazz and has no need to work, he lives in an apartment with Chick his best friend. Chick is obsessed with the literature of Jean Sol-Patre (Jean-Paul Satre in the real world) and has little money himself. The apartment is also home to Nicholas who is both chef and chauffeur to Colin and a couple of mice who all live happily together. Nicholas introduces Colin to his cousin Chloé and Chick meets her friend Alise. Both men fall in love with the two girls and Colin marries Chloé who moves into the apartment. He lends some money to Chick who instead of marrying Alise spends his dublazons (it is an alternative world) on the works of Sol-Patre who seems to be publishing books and articles almost every week. Chloé becomes ill with a growth in her lung and Colin finds a doctor who treats her with new techniques. The treatment is expensive and Colin spends all his money on treatments and flowers, believing that cut flowers in Chloé's sick room will help her recovery (cut flowers are an expensive item in France). Chloe does not recover, Colin is impoverished and searches for work and Chick spends the last of his money on a pair of old trousers previously owned by Sol-Patre.

This is a tragi-comedy love story shot through with satire, magic realism and naivety. It is told in short chapters that have a certain grip on the real world then lurch into parody, this reader was continually wrong footed when at the start of the novel, but quickly learn't to go with the flow. The first chapter introduces us to Colin and describes his toilette in some detail and we meet Chick and Nicholas and then rather bizarrely in the cuisine are the mice who are dancing happily in the rays of the sunshine and Colin in passing by to see what is cooking caresses them lovingly. There is much talk about food and jazz as the first chapter comes to the end. From then on the chapters increasingly become a little more surreal until we are in another world which seems an awful parody of this one. There are some great moments (or little chapters) in the book: Nicholas takes Colin and Chloe for a drive and to avoid traffic they take a short cut on unmade roads through a copper mining area with open foundries and Chloe is frightened by the workers and the destroyed landscape, there is the strange hospital of Professor Mangemanche, there are the efforts of Colin to raise money by selling his pianococktail; an invention that mixes drinks when a tune is played on the keyboard, the burning of the libraries and the murder of Sol-Patre and finally the tragedy of Chloés sick room

In this surreal world which becomes more tragic Boris Vian takes aim and satirises religion, celebrity status, fine dining, the medical profession, discrimination and it seems many other aspects of contemporary life. The frothy good natured approach that Vian takes in his writing only starts to slip a little in the final chapters, but it is a book with its own unique style and as such succeeds wonderfully. Funny and sad at the same time and a five star read.

14AlisonY

I think I have an unread cope of Le Petit Prince somewhere on my shelves. It's popped up several times in various mediums over Christmas - you're reminding me I should actually read it.

15dchaikin

>13 baswood: I’m entertained by your description, although not sure of I would make any sense of this one.

16Dilara86

>13 baswood: I loved this book, as a teenager! Then I lent it and never got it back...

Have you seen Michel Gondry's recent adaptation? For some reason, it's called Mood Indigo in English.

Have you seen Michel Gondry's recent adaptation? For some reason, it's called Mood Indigo in English.

17LolaWalser

Hi, baswood, liking the thread a lot already. Have you listened to Vian's music, or is that a stupid question... I haven't bothered to look up his jazz playing but I like his songs. Ref: Boris Vian - La complainte du progrès (1956) The video ends with a clip of Vian and Jeanne Moreau in Vadim's Les liaisons dangereuses. That's the 18th-century Laclos set all to jazz, btw.

18baswood

>16 Dilara86: Mood Indigo - title of a song by Duke Ellington, so I suppose that makes sense. The English translation of L'écume des jours (book) is Froth of the Daydream which doesn't make much sense to me either. I have not seen the film yet but will look out for it.

19baswood

>17 LolaWalser: Thank you for the link Lola I enjoyed the song and the clip afterwards of Vian.

20Dilara86

>17 LolaWalser: That was the song that played in my head all evening yesterday, after reading this thread! I was actually going to link to the same Youtube video, but you beat me to it!

More generally, Vian's songs - especially Le déserteur (English subtitles), La complainte du progrès, and On n'est pas là pour se faire engueuler - are a must to anyone interested in French culture, and postwar/fifties France in particular. They've become part of our "cultural vocabulary", to the point where people don't necessarily realise that they're quoting Vian. Personally, I have a soft spot for Higelin's take on Vian, as in Priez pour Saint-Germain-des-prés and La java des chaussettes à clous.

>18 baswood: The film is available on Netflix. I'm not necessarily recommending it warmly (not over the book anyway!), but Gondry's visual universe is well suited to the novel, and it certainly sparked up interest in non-French-speaking countries.

More generally, Vian's songs - especially Le déserteur (English subtitles), La complainte du progrès, and On n'est pas là pour se faire engueuler - are a must to anyone interested in French culture, and postwar/fifties France in particular. They've become part of our "cultural vocabulary", to the point where people don't necessarily realise that they're quoting Vian. Personally, I have a soft spot for Higelin's take on Vian, as in Priez pour Saint-Germain-des-prés and La java des chaussettes à clous.

>18 baswood: The film is available on Netflix. I'm not necessarily recommending it warmly (not over the book anyway!), but Gondry's visual universe is well suited to the novel, and it certainly sparked up interest in non-French-speaking countries.

21baswood

>20 Dilara86: I am certainly interested into dipping more into French Culture, having become naturalised French last year I have a lot of catching up to do, thank you for the links.

22AnnieMod

>13 baswood:

I definitely need to reread this one - I read it back in my teens and fell in love with Vian's style but I am pretty sure I missed quite a lot of it (and I am pretty sure I read Exupery a few years after that for the first time). Wonderful review!

I definitely need to reread this one - I read it back in my teens and fell in love with Vian's style but I am pretty sure I missed quite a lot of it (and I am pretty sure I read Exupery a few years after that for the first time). Wonderful review!

23raton-liseur

>20 Dilara86: I would add to the list La Java des bombes atomiques, unfortunately I have not found a subtitled version.

I prefer the singer than the writer, but I have been meaning for some time to read J'irai cracher sur vos tombes, written under one of many pen names that Boris Vian took, and supposed to be written in an American style.

I prefer the singer than the writer, but I have been meaning for some time to read J'irai cracher sur vos tombes, written under one of many pen names that Boris Vian took, and supposed to be written in an American style.

24kidzdoc

Ooh, you got me with your excellent review of L'écume des Jours, Barry! That sounds right up my alley, so I purchased the Kindle version of one of the English translations of it, titled Mood Indigo, just now. I may be reading it very soon.

25baswood

Beyond Infinity, Robert Spencer Carr and Monsters of the Ray, A Hyatt Verrill

Welcome to ARMCHAIR FICTION We are a new company dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Here you will find new, "Extra Large" paperback editions of top genre fiction from the past. Welcome indeed because they have republished a story from 1951 that I wanted to read and a bonus story with Monsters of the Ray.

Robert Spencer Carr specialised in short fiction and was actively published between 1925 and 1952. Beyond Infinity is novella length and tells s story of two rival scientists finally working together in their retirement years to build and fund a rocket ship. There is a certain amount of distrust between the two still and one of them hires a detective to search for a missing person; a woman whom he loved, but chose to marry another of his rivals. The detective with the scientists niece tracks down the woman and discovers that she has volunteered to be a guinea pig in the clandestine spaceflight. This is a good story well held together with a satisfying conclusion and Spencer Carr creates two strong female characters with a nice twist to the end of the story. Plenty of atmosphere and some tension.

I was more surprised by Monsters of the Ray which started with almost a record number of cliches in the first three pages, but afterwards set out to tell another good story. A reclusive scientist has built himself a laboratory in the mountains of Peru amongst an old Inca site. An anthropologist/archeologist tracks him down and becomes fascinated by his work. The scientist is trying to discover how the ancient Indians managed to cut stone to build their temples and an impressive bridge across a canyon. The archeologists discovery of a curiously shaped container leads to much speculation as to its use, this together with an Indian legend of Gods visiting the earth entices the scientists to explore the mystery container. A portal into another world results with dire consequences.

Both of the stories are not worried about scientific facts and don't let them get in the way of a good story. This is pulp fiction after all, but the writing is of a good standard. Armchairfiction are specialising in republishing stories from the golden age of science fiction, but I have probably outgrown my need for them now - 3 stars.

26LolaWalser

>20 Dilara86:

I didn't know Higelin, fun versions, thanks.

>23 raton-liseur:

Agreed on La java... --probably my fave; I linked the other song for the clip at the end...

Speaking of translations, I haven't read the English versions but I recall there's an edition of L'écume... in English called Foam of the daze--no idea about the quality of the text but the title strikes me as promisingly clever.

I didn't know Higelin, fun versions, thanks.

>23 raton-liseur:

Agreed on La java... --probably my fave; I linked the other song for the clip at the end...

Speaking of translations, I haven't read the English versions but I recall there's an edition of L'écume... in English called Foam of the daze--no idea about the quality of the text but the title strikes me as promisingly clever.

27sallypursell

Stopping by to wish you a Happy New Year, and to drop off my star, Barry. You always read interesting things, and I like glancing off your thread.

28arubabookwoman

Lots of good books from 1951. A few years ago, I was trying to read the books published each year of my life as a way of choosing books to read that were already on my shelf. I got from1950 to 1953.

I read The Cruel Sea several years ago, and though it's not great literature, I really liked it, enough that I've bought another book by Monsarrat, though not yet read it. It is a book I remember my father reading when I was a child (he liked war books). Many, many years ago I read From Here To Eternity, and also liked it, so I guess I must like war books too.

I read The Cruel Sea several years ago, and though it's not great literature, I really liked it, enough that I've bought another book by Monsarrat, though not yet read it. It is a book I remember my father reading when I was a child (he liked war books). Many, many years ago I read From Here To Eternity, and also liked it, so I guess I must like war books too.

29baswood

Anthony Burgess - The Devil's Mode

When I was collecting together the unread books from my shelves, I realised I had five by Burgess; which I probably bought in a charity shop as a sort of job lot. The Devil's Mode was the third of the five and the most disappointing. It is a collection of nine short stories, with one of them (Hun) being of novella length and probably the most pointless one of the collection.

They start of well with "A Meeting in Valladolid" where Burgess imagines the 40 year old Shakespeare being a member of a trade and culture delegation sent over to Spain to heal relations between the two countries after the succession to the English throne of James I. Of course it is Shakespeare who suffers most from sea sickness and he spends an uncomfortable time in Spain organising shortened productions of his plays as entertainments; choosing Titus Andronicus in the first instance thinking that the Spanish will enjoy the buckets of blood used in the spectacle. He meets Miguel de Cervantes, who is as irascible as his character Don Quixote. From the nuggets of history that are known about Shakespeare, Burgess has made an amusing historical fiction short story (I am not sure that we know that the bard suffered sea sickness or that he went to Spain and met Cervantes). This is a template for several other stories. "The Most Beautiful" imagines a student lecture in Wittenberg at the time of Martin Luther. 'The Cavalier of the Rose' imagines Maria Theresa of Austria in bed with her young lover which develops into a Boccaccio like farce. In "1889 and the Devil's Mode" he imagines certain European poets and musicians visiting England and Ireland: Debussy goes to a brothel in Dublin with Stephan Mallarme and then they meet Browning and Christina Rossetti. These first four historical fiction stories are cleverly worked, but by the time that we get to 'The Devils Mode' it is only Burgesses cleverness that is on show. One could say Story? what Story?

There follows two stories that are set in Malaysia and tell spicy tales of European's sexual relations with native women. These feel like chapters that didn't quite make the cut for Burgesse's previous novels collected as the Malayan trilogy with their casual sexism and racism. Both forgettable if you have read any of his previous books. A curious modern story about a man spending his inheritance on air travel is next and is more original in conception, but this is all too quickly followed by Hun. The Hun is Atilla and Burgess imagines the barbarian hordes conquest of much that was Roman Europe. As an exercise in trying to understand Atilla it makes no sense with Burgess tackling that problem with 20th century hindsight. Christopher Marlowe was much more successful in the late 16th century with his depiction of another Asiatic conqueror Tamburlaine (Tamurlane) in his play Tamburlaine the great. With Burgess we get 15th century warriors speaking like 20th century politicians and descriptions of the barbarities enacted against the towns and cities in their way. This reader had trouble staying awake (but maybe the wine didn't help). The final story is a Sherlock Holmes adventure and this is more successful and fitting perhaps because Holmes is even more clever than Burgess.

These stories were collected and published in 1989 and perhaps with their 'intellectual' dazzle they seemed more original, but reading them today I found that many of them had lost their sparkle and a novella (Hun) has never seemed so long. 3 stars.

30tonikat

>5 baswood: thanks for that review, very interesting. It's only been as an adult that I learned of Auden's connection to the north pennines, which I find satisfying always looking for literary localish links. You may be interested in this , if you are not aware of it, it may have some useful info too - https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/oct/10/sean-obrien-how-wh-audens-spell-no...

You've made me think to read it soon myself - but I may put it off to have looked at his earlier work more fully first. I lack in knowing the earlier works and wondered if they would have helped when i read The Shield of Achilles.

I also enjoyed the Vian discussion, will listen to the link. I don't think of Burgess for short stories, I'll have to think about that and see if there were more, but this does not sound liek a priority, thouhg in a way I do liek the idea of sort of making that modern-speak Hunnish, cos it can seem so.

edit - lol now watched la Complainte du progres -- made me think of the start of Trainspotting. I'll watch the rest soon.

You've made me think to read it soon myself - but I may put it off to have looked at his earlier work more fully first. I lack in knowing the earlier works and wondered if they would have helped when i read The Shield of Achilles.

I also enjoyed the Vian discussion, will listen to the link. I don't think of Burgess for short stories, I'll have to think about that and see if there were more, but this does not sound liek a priority, thouhg in a way I do liek the idea of sort of making that modern-speak Hunnish, cos it can seem so.

edit - lol now watched la Complainte du progres -- made me think of the start of Trainspotting. I'll watch the rest soon.

31baswood

Elizabethan Sonnet-Cycles II: Thomas Lodge - Phillis: Honored with Pastoral Sonnets, Elegies and Amorous Delights. Part of a cycle edited by Martha Foote Crow (Free at Project Gutenberg)

In the mid 1590's there seemed to be a rush to get poetry collections into print, perhaps caused by the publishing of Sir Philip Sydneys Astrophil and Stella in 1591. Many of these collections have been filed away under the genre of The Elizabethan Love Sonnet. They took as a template Petrarch's Canzoniere in which the poet by means of sonnets, odes, elegies and songs proclaimed his undying love for Laura. Petrarch took over 44 years to put his collection together only brought to its completion by his death in 1374. Over two hundred years later and still feeling the legacy of the idea of courtly love the Elizabethans who followed Sidney were seeming to make their collections little more than poetical exercises. In many cases there seems to be no actual unrequited love affair involved; it is more an exercise for the poet to describe his degrees of suffering for an unobtainable love match. The poetry has become academic and abstract as the search for: or in many cases the refinement of existing imagery is the reason for the appearance of the collections at the publishing houses.

When approaching one of the love sonnet collections I ask myself what's new. Is there anything here to distinguish it from those that have gone before. In the case of Thomas Lodge's Phillis the answer to the first question is no and the answer to the second question is 'not much' and if the reader was interested in "Amorous Delights" promised in the subtitle then he would be disappointed. Thomas lodge was the son of the Lord Mayor of London and tried his hand at various types of written work: plays, pamphlets, social and morale tracts, historical prose, romantic stories and of course poetry. His most successful work was the romantic love story Rosalynde, which does contain some poetry. He undertook at least three sea voyages and on one of them he wrote Phillis, sonnet II:

You sacred sea-nymphs pleasantly disporting

Amidst this wat'ry world, where now I sail;

If ever love, or lovers sad reporting,

Had power sweet tears from your fair eyes to hail;

And you, more gentle-hearted than the rest,

Under the northern noon-stead sweetly streaming,

Lend those moist riches of your crystal crest,

To quench the flames from my heart's Ætna streaming;

And thou, kind Triton, in thy trumpet relish

The ruthful accents of my discontent,

That midst this travel desolate and hellish,

Some gentle wind that listens my lament

May prattle in the north in Phillis' ears:

"Where Phillis wants, Damon consumes in tears."

The positives from the collection are the freshness of Lodge's poetry; he does not draw so much on classical antiquity and obscure imagery and his poetry can sing with a more natural voice than some. Although the collection does not seem to go anywhere; there is no story line, it has been shaped as a pastoral and so there are a couple of eglogs (ecologues) and a debate between Damon and Damades while they tend their flocks of sheep. Perhaps a man like Lodge who was adept at satirical works and many other kinds of writing felt constrained by the love sonnet format. The frustration of the speaker comes through in the final five eight line stanzas ending with:

"Prime youth lusts not age still follow,

And make white these tresses yellow;

Wrinkled face for looks delightful

Shall acquaint the dame despightful;

And when time shall eat thy glory,

Then too late thou wilt be sorry.

Siren pleasant, foe to reason,

Cupid plague thee for thy treason!"

The final sonnet is ambiguous and seems to take the poet back to wondering if his poetry will survive. A collection of poems not without interest, but they might seem dull to some readers and so 3 stars.

Here is one of his more successful sonnets from the collection even if that final line does not quite fit.

Burst, burst, poor heart! Thou hast no longer hope;

Captive mine eyes unto eternal sleep;

Let all my senses have no further scope;

Let death be lord of me and all my sheep!

For Phillis hath betrothèd fierce disdain,

That makes his mortal mansion in her heart;

And though my tongue have long time taken pain

To sue divorce and wed her to desert,

She will not yield, my words can have no power;

She scorns my faith, she laughs at my sad lays,

She fills my soul with never ceasing sour,

Who filled the world with volumes of her praise.

In such extremes what wretch can cease to crave

His peace from death, who can no mercy have!

In the mid 1590's there seemed to be a rush to get poetry collections into print, perhaps caused by the publishing of Sir Philip Sydneys Astrophil and Stella in 1591. Many of these collections have been filed away under the genre of The Elizabethan Love Sonnet. They took as a template Petrarch's Canzoniere in which the poet by means of sonnets, odes, elegies and songs proclaimed his undying love for Laura. Petrarch took over 44 years to put his collection together only brought to its completion by his death in 1374. Over two hundred years later and still feeling the legacy of the idea of courtly love the Elizabethans who followed Sidney were seeming to make their collections little more than poetical exercises. In many cases there seems to be no actual unrequited love affair involved; it is more an exercise for the poet to describe his degrees of suffering for an unobtainable love match. The poetry has become academic and abstract as the search for: or in many cases the refinement of existing imagery is the reason for the appearance of the collections at the publishing houses.

When approaching one of the love sonnet collections I ask myself what's new. Is there anything here to distinguish it from those that have gone before. In the case of Thomas Lodge's Phillis the answer to the first question is no and the answer to the second question is 'not much' and if the reader was interested in "Amorous Delights" promised in the subtitle then he would be disappointed. Thomas lodge was the son of the Lord Mayor of London and tried his hand at various types of written work: plays, pamphlets, social and morale tracts, historical prose, romantic stories and of course poetry. His most successful work was the romantic love story Rosalynde, which does contain some poetry. He undertook at least three sea voyages and on one of them he wrote Phillis, sonnet II:

You sacred sea-nymphs pleasantly disporting

Amidst this wat'ry world, where now I sail;

If ever love, or lovers sad reporting,

Had power sweet tears from your fair eyes to hail;

And you, more gentle-hearted than the rest,

Under the northern noon-stead sweetly streaming,

Lend those moist riches of your crystal crest,

To quench the flames from my heart's Ætna streaming;

And thou, kind Triton, in thy trumpet relish

The ruthful accents of my discontent,

That midst this travel desolate and hellish,

Some gentle wind that listens my lament

May prattle in the north in Phillis' ears:

"Where Phillis wants, Damon consumes in tears."

The positives from the collection are the freshness of Lodge's poetry; he does not draw so much on classical antiquity and obscure imagery and his poetry can sing with a more natural voice than some. Although the collection does not seem to go anywhere; there is no story line, it has been shaped as a pastoral and so there are a couple of eglogs (ecologues) and a debate between Damon and Damades while they tend their flocks of sheep. Perhaps a man like Lodge who was adept at satirical works and many other kinds of writing felt constrained by the love sonnet format. The frustration of the speaker comes through in the final five eight line stanzas ending with:

"Prime youth lusts not age still follow,

And make white these tresses yellow;

Wrinkled face for looks delightful

Shall acquaint the dame despightful;

And when time shall eat thy glory,

Then too late thou wilt be sorry.

Siren pleasant, foe to reason,

Cupid plague thee for thy treason!"

The final sonnet is ambiguous and seems to take the poet back to wondering if his poetry will survive. A collection of poems not without interest, but they might seem dull to some readers and so 3 stars.

Here is one of his more successful sonnets from the collection even if that final line does not quite fit.

Burst, burst, poor heart! Thou hast no longer hope;

Captive mine eyes unto eternal sleep;

Let all my senses have no further scope;

Let death be lord of me and all my sheep!

For Phillis hath betrothèd fierce disdain,

That makes his mortal mansion in her heart;

And though my tongue have long time taken pain

To sue divorce and wed her to desert,

She will not yield, my words can have no power;

She scorns my faith, she laughs at my sad lays,

She fills my soul with never ceasing sour,

Who filled the world with volumes of her praise.

In such extremes what wretch can cease to crave

His peace from death, who can no mercy have!

32baswood

Elizabethan Sonnet-Cycles II Licia or Poems of love in honour of the admirable and singular virtues of his lady, to the imitation of the best Latin poets and others by Giles Fletcher. This is the second sonnet collection in the book edited by Martha Foote Crow >31 baswood:

Giles Fletcher came from a well to do family, educated at Eton and Trinity college. He was known for his public services, not as a poet or courtier. He claimed that Lucia was written at a time of idleness and he did it only to try his humour. He claimed that love was a goddess and the subject was not for a vulgar head, a base mind, an ordinary conceit, or a common person. He was claiming that his collection of poems were an exercise in writing poetry and it is clear that there never was a Licia; she was an invention that would be the object of his poems.

When the title of the collection refers to them as being "the imitation of the best Latin poets" it is no surprise to find them unoriginal in form and subject. There are 52 sonnets, an ode, a dialogue, a poetical maze and finally an elegy. On the plus side is that they are well composed and read easily. They are written without some of the poetical flourishes of his contemporaries with his imagery being less fantastic than some, mainly sticking to the well worn template. He does occasionally rise above the commonplace take sonnet 6 as an example:

My love amazed did blush herself to see,

Pictured by art, all naked as she was.

"How could the painter know so much by me,

Or art effect what he hath brought to pass?

It is not like he naked me hath seen,

Or stood so nigh for to observe so much."

No, sweet; his eyes so near have never been,

Nor could his hands by art have cunning such;

I showed my heart, wherein you printed were,

You, naked you, as here you painted are;

In that my love your picture I must wear,

And show't to all, unless you have more care.

Then take my heart, and place it with your own;

So shall you naked never more be known.

He proved to be more unselfish than some:

First did I fear, when first my love began;

Possessed in fits by watchful jealousy,

I sought to keep what I by favour won,

And brooked no partner in my love to be.

But tyrant sickness fed upon my love,

And spread his ensigns, dyed with colour white;

Then was suspicion glad for to remove,

And loving much did fear to lose her quite.

Erect, fair sweet, the colors thou didst wear;

Dislodge thy griefs; the short'ners of content;

For now of life, not love, is all my fear,

Lest life and love be both together spent.

Live but, fair love, and banish thy disease,

And love, kind heart, both where and whom thou please.

The last sonnet of the collection hints that he has gained the object of his desire, but it is fairly pedestrian and no cause for celebration. The final three part elegy pus the reader out of his misery:

Down in a bed and on a bed of down,

Love, she, and I to sleep together lay;

She like a wanton kissed me with a frown,

Sleep, sleep, she said, but meant to steal away;

I could not choose but kiss, but wake, but smile,

To see how she thought us two to beguile.

It is not difficult to read Fletcher's collection, but most of his poetry slips by without making an impression and the long A Lover's Maze is best avoided. It is a further example of a sonnet collection which will be most appreciated by people that enjoy the Elizabethan sonnet form. I found some enjoyment but would rate it as 2.5 stars.

Giles Fletcher came from a well to do family, educated at Eton and Trinity college. He was known for his public services, not as a poet or courtier. He claimed that Lucia was written at a time of idleness and he did it only to try his humour. He claimed that love was a goddess and the subject was not for a vulgar head, a base mind, an ordinary conceit, or a common person. He was claiming that his collection of poems were an exercise in writing poetry and it is clear that there never was a Licia; she was an invention that would be the object of his poems.

When the title of the collection refers to them as being "the imitation of the best Latin poets" it is no surprise to find them unoriginal in form and subject. There are 52 sonnets, an ode, a dialogue, a poetical maze and finally an elegy. On the plus side is that they are well composed and read easily. They are written without some of the poetical flourishes of his contemporaries with his imagery being less fantastic than some, mainly sticking to the well worn template. He does occasionally rise above the commonplace take sonnet 6 as an example:

My love amazed did blush herself to see,

Pictured by art, all naked as she was.

"How could the painter know so much by me,

Or art effect what he hath brought to pass?

It is not like he naked me hath seen,

Or stood so nigh for to observe so much."

No, sweet; his eyes so near have never been,

Nor could his hands by art have cunning such;

I showed my heart, wherein you printed were,

You, naked you, as here you painted are;

In that my love your picture I must wear,

And show't to all, unless you have more care.

Then take my heart, and place it with your own;

So shall you naked never more be known.

He proved to be more unselfish than some:

First did I fear, when first my love began;

Possessed in fits by watchful jealousy,

I sought to keep what I by favour won,

And brooked no partner in my love to be.

But tyrant sickness fed upon my love,

And spread his ensigns, dyed with colour white;

Then was suspicion glad for to remove,

And loving much did fear to lose her quite.

Erect, fair sweet, the colors thou didst wear;

Dislodge thy griefs; the short'ners of content;

For now of life, not love, is all my fear,

Lest life and love be both together spent.

Live but, fair love, and banish thy disease,

And love, kind heart, both where and whom thou please.

The last sonnet of the collection hints that he has gained the object of his desire, but it is fairly pedestrian and no cause for celebration. The final three part elegy pus the reader out of his misery:

Down in a bed and on a bed of down,

Love, she, and I to sleep together lay;

She like a wanton kissed me with a frown,

Sleep, sleep, she said, but meant to steal away;

I could not choose but kiss, but wake, but smile,

To see how she thought us two to beguile.

It is not difficult to read Fletcher's collection, but most of his poetry slips by without making an impression and the long A Lover's Maze is best avoided. It is a further example of a sonnet collection which will be most appreciated by people that enjoy the Elizabethan sonnet form. I found some enjoyment but would rate it as 2.5 stars.

33LolaWalser

my heart's Ætna

*snicker* /twelve-year-old

This sort of thing is why I admired Shakespeare's sonnet about the plain Jane mistress so much, the one beginning "My Mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun". If hair be wires, black wires grow upon her head! Surely he was taking a dig at these guys?

*snicker* /twelve-year-old

This sort of thing is why I admired Shakespeare's sonnet about the plain Jane mistress so much, the one beginning "My Mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun". If hair be wires, black wires grow upon her head! Surely he was taking a dig at these guys?

34baswood

>33 LolaWalser: I am sure he was.

35baswood

The Strange case of Dr Jekyll and Mister Hyde - Robert Louis Stevenson

First published in 1886 as a penny dreadful and subsequently filmed many times Stevenson's Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde will be familiar to many readers. The idea of a dual personality: one inherently good and one inherently evil inhabiting one body and the battle between the two certainly fired the publics imagination and it was an immediate success. I came to read as part of my progress through victorian novels that contain the seeds of science fiction. This book does more than contain the seeds it gave vent to a sub-genre all of its own; the crazy scientist working in secret on a potion that will enhance his life in some drastic faction, but has unfortunate side effects. Jules Verne's Doctor Ox published in 1872 had a comparable theme and Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Doran Grey published in 1891 arguably developed the idea, but these both had elements of humour to lighten the reading: Stevenson's book has about as much humour as Scottish bagpipes. It is dark and gothic in a way that gives a nod to the literature of Edgar Allan Poe.

It is a novella in length with the final third being epistolary in form and although it is Victorian and gothic there is a tightness to the writing. The mystery moves smartly forward with Stevensons characterisation's adding to the feeling of unease that the author generates. It is a story revelling in its maleness, the only female character in an unnamed maid who witnesses a murder. It is written as a mystery and so the insights into the characters of Jekyll and Hyde are only revealed in the fairly long denouement. Mr Utterson the protagonist is by his own admission dull, but trustworthy and he is aided by his cousin Richard Enfield said to be a man about town but gives little evidence of it. The focus of the story is on the mystery of Jekyll and Hyde and I think this is why it succeeds so well along with its exploration into the murky dualities of Victorian men.

It is little more than an afternoons read and it might surprise people who have only seen the movie versions. I enjoyed it and so 4 stars.

36SassyLassy

>35 baswood: This is a book that should be read more instead of going along with the film versions. In addition to all the good things you mention, I was impressed with how well Stevenson captured the duality in way that readers today would recognize as illness.

That's quite a cover.

I'll be interested in what else the Victorians throw your way.

edited for spelling

That's quite a cover.

I'll be interested in what else the Victorians throw your way.

edited for spelling

37dchaikin

>31 baswood: >32 baswood: I’m grateful for these posts, and the examples. ... The examples might be enough of the actual poetry for me.

>35 baswood: fun review. Sounds like you were ok with RLS’s lack of humor here.

>35 baswood: fun review. Sounds like you were ok with RLS’s lack of humor here.

38raton-liseur

>35 baswood: I have still not read this novella (but I will, in a distant future...). I have not watched film either, but read a terrific graphic novel adaptation by Mattoti, Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde. It almost literally made me sick, which did not encourage me to read the novel, but it was an interesting way of getting acquainted with the book.

39baswood

A Question of Upbringing - Anthony Powell - 1951

A Buyer's Market - Anthony Powell - 1952

The Acceptance World - Anthony Powell - 1955

The next book on my 1951 reading list was A question of Upbringing; this is the first part of Anthony Powell's 12 volume series A Dance to the Music of Time. It was much better value to buy the first three volumes in one book rather than just the first volume and as they were there in front of me I read all three volumes: I am just grateful that I did not buy all 12. Powells immense saga follows the lives of a number of individuals who meet as students at their Public School in the early 1920's. We follow the story in the first person through the eyes and many thoughts of Nick Jenkins, who like most of his school friends comes from a well-to-do family and these three books take us up to 1933. Anthony Powell was educated at Eton and Balliol college Oxford and his series of novels has the feel of an autobiography, certainly the milieu of Public school and debutante balls and then sliding into well paid positions of employment either in the city or through contacts made at University has a ring of authenticity. The social milieu could be described as upper middle class with plenty of Lords and Ladies hovering around the upper echelons.

Readers seem to have a love-hate relationship with this series of books and I can understand just why that is. Powell writes, as one might not be too surprised from his background, with a plum in his mouth and sometimes that plum becomes so large that the reader losses much of what is said. His long sentences with their many sub-clauses can become indistinct at best and completely obfuscate any meaning at worst. I lost count of the number of times I got to the end of one of these epics with only a vague impression of what I had just read. This style of writing is particularly evident in the second volume, and although it does occurs in volume three; The Acceptance World this book is a little more focused. One might give credit to Powell for imitating the confused thoughts of a 20 year old just making his way in the world, but I think this would be generous. Much Of volume 2 is focused on two events a debutants ball and a rather more bohemian party that some stragglers get to afterwards. Our protagonist Nick while spending much time describing the details of the guests dress and manners, their opulent surroundings and some of the events he witnesses, seems at a loss to understand their behaviour and even incidents in which he becomes involved remain a bit of a mystery.

Powell looks at everything through his protagonist Nick from an establishment point of view. This is a novel that reinforces the rigid class system that existed for wealthy people in the 1920's-30's and one could argue that Powell has his finger on the pulse of this era, however I sense an admiration of the social milieu in which he places his characters, it is though he is saying how wonderful it all was. One of the characters Widmerpool (we hardly ever learn their Christian names) who is less wealthy than most and realises he must work twice as hard as his contemporaries to get on says "brains and hard work are of very little avail unless you know the right people". This proves to be over optimistic because it is not the connections you might be able to forge, but the connections that your father or grandfather were able to make. It was all down to the position of your family in society. Widmerpool like other characters who were not from the right families are figures of fun in Powells hands, all the jokes are on them because they do not know how to behave correctly. It is all very well to have an accurate description of the young wealthy class in the period in which they lived, but not perhaps at the expense of all else. Reading the novels made me feel that they were outdated, but then thinking about the public school boys that currently run the British government in 2021; perhaps nothing much has changed.

Powells characterisations of his female characters are depressingly familiar; judged on their attractiveness to the male gaze and their propensity to conform to their partners wishes. Independently minded women are seen as either a threat or something to be managed and forever remain a mystery to their male counterparts. Nick himself who is very much a cypher in that he is a witness to events that happen around him, rather than instigating any of them, becomes in the third volume active in pursuing a love affair, but he is like a blind man stumbling towards an urge that needs satisfying.

There is much in these novels that were not to my taste, but they can have a dream like quality enhanced by Powells writing style. Characters did not elicit my care or sympathy for their predicaments, but I did enjoy the slow pace of the events and the insight of a world that I know existed and perhaps still exists. I will not be tempted to read any more of the books in this series; three were enough and I rate them as follows:

A Question of Upbringing - 3 stars

A Buyers Market - 2.5 stars

The Acceptance World - 4 stars.

40LolaWalser

>39 baswood:

Ahh, I'm glad at the lack of enthusiasm, I detested the thing--well, the first book, didn't go past it. Couldn't believe he apparently thought he was "doing a Proust"... how sadly deluded. Both about Proust and his own powers.

Powell writes, as one might not be too surprised from his background, with a plum in his mouth and sometimes that plum becomes so large that the reader losses much of what is said.

Ha, this brought back his tone to me exactly.

Ahh, I'm glad at the lack of enthusiasm, I detested the thing--well, the first book, didn't go past it. Couldn't believe he apparently thought he was "doing a Proust"... how sadly deluded. Both about Proust and his own powers.

Powell writes, as one might not be too surprised from his background, with a plum in his mouth and sometimes that plum becomes so large that the reader losses much of what is said.

Ha, this brought back his tone to me exactly.

41thorold

>39 baswood: Yes, he was over-rated, and over-rated himself too. I enjoyed immersing myself in the sequence when I first discovered it, but I don’t really feel I could face going back to it now!

I find there are quite a few scenes from Dance that have stuck in my mind, though, Powell did occasionally have something interesting to say, if not twelve books worth. The WWII books are the best, probably.

I much prefer Simon Raven, who never thought of himself as writing great literature, just getting his own back on people he didn’t like (i.e. everyone).

I find there are quite a few scenes from Dance that have stuck in my mind, though, Powell did occasionally have something interesting to say, if not twelve books worth. The WWII books are the best, probably.

I much prefer Simon Raven, who never thought of himself as writing great literature, just getting his own back on people he didn’t like (i.e. everyone).

42dchaikin

>39 baswood: admiring your tenacity. And your limits. This review is will likely serve as all I will ever know of Anthony Powell.

43baswood

Malcolm Bradbury - Who do you think you are?, Malcolm Bradbury

Malcolm Bradbury was an English academic and author and published this collection of short stories in 1976. This collection of seven short stories and nine parodies are largely satirical, based around life in academia. Bradbury held posts in both England and America and these stories criss cross the Atlantic ocean. The satire is sharp and witty; if a little one paced due to its subject matter not straying far from the campus. His first story "A Goodbye to Evadne Winterbottom" starts as follows:

Perhaps I should begin by saying all that follows I write if a little frankly as a professional man

This could be said about all the stories if he had added "prone to dalliances with the opposite sex" This first story concerns a welfare psychiatrist (if there is such a thing) and his patient Evadne Winterbottom whose issues make the psychiatrist examine his own life and who he wants to be. "A Very Hospitable Person" is set in America where an English couple newly working at the college are invited to a meal by an American work colleague, whose wife makes overt sexual comments which embarrasses the English couple. "Who Do You think You Are" is an intellectual quiz programme devised for the BBC where the expert participants must carry out an in depth personality review of a character selected at random, using their own specialist knowledge and ends with the experts psychoanalysing each other. This is one of the best stories with Bradbury using his insight in how the BBC worked at the time. "The Adult Education Class" is also very good telling a story of a poetry class, whose professor has to cope with one of his former college pupils, involved in a take over bid. "Nobody Here in England" is actually set in an American college who have invited an "expert" on George Bernard Shaw, who wants to make a benefaction of love letters that she claims to have received from him. The college must decide if she is genuine. "A Breakdown" is a story of a mature student falling in love with her college professor. The final story "Composition" is about a visiting English professor in America becoming involved with students, who will do anything to get better grades.

Following the stories there are nine short parodies that could have been written by writers such as Muriel Spark, Lawrence Durrell, John Braine, Alan Sillitoe etc; authors from the 1960's. A sort introductory paragraph informs the reader who Bradbury is parodying, but much of the humour would be lost if you were not familiar with the authors in question.

I found the stories witty and entertaining, there were no read duds and as satirical slices of life from the teaching side of the campus of five decades ago, they work well. This one might go back on the bookshelf 3 stars.

44edwinbcn

>39 baswood: Same feeling here, and almost the same rating fro the first three novels of Dance to the Music of time, which I read in July last year. I hope to finish the whole hing this year.

45baswood

Wasp - Eric Frank Russell

Pulp science fiction from 1957 which has somehow become part of the Masterwork science fiction series. It holds the premise that a single person can seriously disrupt a world government if it goes about it in the right way; the analogy is of a wasp in a car full of people that can cause a car crash and this may be true because a friend of mine drove into a ditch when a wasp flew in his car window. While a wasp could cause a car crash we are really into a fantasy world in thinking that one person could be instrumental in bringing down an alien military government with the tactics that the protagonist James Mowry uses in this novel. There is not much science but plenty of fiction.

As a serialised entry in a 1950's pulp magazine this could have been splashed on the front page, but as an example of the cutting edge of science fiction writing in the late 1950's it does not cut. 3 stars.

46baswood

Thomas Lodge - The LIfe and Death of William Longbeard.

Thomas Lodge was a university man who made his living as an author in Elizabethan England. He never finished his law degree, but instead became a prolific writer in fiction, non fiction, drama and poetry. This short chronicle from 1593 is written in a genre that has come to be known as historical fiction, however in Elizabethan times no such prose work would have been printed without a selection of poetry and songs and this one is no exception with thirteen items inserted by Lodge. The source of Lodge's narrative is mainly Robert Fabyan's chronicle which was reprinted in 1559 and what is most interesting are the additions that Lodge made to the text which is otherwise fairly well condensed.

This is the story of a twelfth century rabble-rouser; William Fitzosbert who claimed to know KIng Richard Ist personally. The outline of the tale is that William Fitzosbert (Longbeard) was an ambitious child prodigy

of a well to do family, who framed his older brother for treason and inherited the family wealth and lands, when his brother was executed. He sought the support of the craftsmen and poor of the city and acted for them in legal disputes, gaining a number of devoted followers. His entourage around the city came to rival many of the courtiers to King Richard and this could not fail to anger the king and finally he was arraigned with nine of his followers on charges of treason. He and his followers were found guilty and they were all hung drawn and quartered.

Apart from the songs and poetry Lodge enhanced the story with two major additions. The first was with an example of the cases brought before the local assizes, where William acted for the plaintiff in this case a woman reduced to poverty by the actions of her landlord. The woman's husband before his death had provided the landlord with a sum of money to invest for him as provision for his family. The investment had not been made and the money spent. William was able to piece together some torn documentation that proved the poor woman's case. Lodge himself was a supplicant to the court over loans and investments of his own properties and had fallen foul of more wealthy opponents and so this was a subject dear to him, but in his addition to the story he stressed the suffering of the poor woman and composed a pitiful lullaby that she sang to her hungry children. To balance the work that William did on behalf of the poor his other addition told a story of his love affair with the unchaste Maudline. He dressed her in finery and her pranking around town caused tongues to wag and William murdered another of her suiters. Lodge takes the opportunity here to add a number of songs and sonnets written to Maudlin by William.

Traitors cannot be countenanced and however much good work William did Lodge stresses that it was his pride and his vanity that set him on his path and with the inclusion of the murder and his subsequent challenge to authority as well as the framing of his brother he was deservedly executed. Lodge ends the story with William's confession and included some spiritual poetry aimed at saving William's soul.

Lodge's lively retelling of William Fitzosbert's story makes an interesting narrative, especially as he portrays two sides to Williams character and he dwells somewhat on the plight of poor people unable to compete with their more wealthy counterparts. However in the final paragraph Lodge is clear that William's fate is an example to those who challenge the accepted order of society.

"Thus ended the life of William Long Beard: a glass for all sorts to look into, wherein the high minded may learn to know the mean and corrupt confusion of their wickedness........."

This is a good example of the better written prose that was appearing at the time, free from the euphuisms of John Lilly. In addition Lodge has used his own experiences to add a further dimension and so 3.5 stars.

Thomas Lodge was a university man who made his living as an author in Elizabethan England. He never finished his law degree, but instead became a prolific writer in fiction, non fiction, drama and poetry. This short chronicle from 1593 is written in a genre that has come to be known as historical fiction, however in Elizabethan times no such prose work would have been printed without a selection of poetry and songs and this one is no exception with thirteen items inserted by Lodge. The source of Lodge's narrative is mainly Robert Fabyan's chronicle which was reprinted in 1559 and what is most interesting are the additions that Lodge made to the text which is otherwise fairly well condensed.

This is the story of a twelfth century rabble-rouser; William Fitzosbert who claimed to know KIng Richard Ist personally. The outline of the tale is that William Fitzosbert (Longbeard) was an ambitious child prodigy

of a well to do family, who framed his older brother for treason and inherited the family wealth and lands, when his brother was executed. He sought the support of the craftsmen and poor of the city and acted for them in legal disputes, gaining a number of devoted followers. His entourage around the city came to rival many of the courtiers to King Richard and this could not fail to anger the king and finally he was arraigned with nine of his followers on charges of treason. He and his followers were found guilty and they were all hung drawn and quartered.

Apart from the songs and poetry Lodge enhanced the story with two major additions. The first was with an example of the cases brought before the local assizes, where William acted for the plaintiff in this case a woman reduced to poverty by the actions of her landlord. The woman's husband before his death had provided the landlord with a sum of money to invest for him as provision for his family. The investment had not been made and the money spent. William was able to piece together some torn documentation that proved the poor woman's case. Lodge himself was a supplicant to the court over loans and investments of his own properties and had fallen foul of more wealthy opponents and so this was a subject dear to him, but in his addition to the story he stressed the suffering of the poor woman and composed a pitiful lullaby that she sang to her hungry children. To balance the work that William did on behalf of the poor his other addition told a story of his love affair with the unchaste Maudline. He dressed her in finery and her pranking around town caused tongues to wag and William murdered another of her suiters. Lodge takes the opportunity here to add a number of songs and sonnets written to Maudlin by William.

Traitors cannot be countenanced and however much good work William did Lodge stresses that it was his pride and his vanity that set him on his path and with the inclusion of the murder and his subsequent challenge to authority as well as the framing of his brother he was deservedly executed. Lodge ends the story with William's confession and included some spiritual poetry aimed at saving William's soul.

Lodge's lively retelling of William Fitzosbert's story makes an interesting narrative, especially as he portrays two sides to Williams character and he dwells somewhat on the plight of poor people unable to compete with their more wealthy counterparts. However in the final paragraph Lodge is clear that William's fate is an example to those who challenge the accepted order of society.

"Thus ended the life of William Long Beard: a glass for all sorts to look into, wherein the high minded may learn to know the mean and corrupt confusion of their wickedness........."

This is a good example of the better written prose that was appearing at the time, free from the euphuisms of John Lilly. In addition Lodge has used his own experiences to add a further dimension and so 3.5 stars.

47sallypursell

>45 baswood: I have a favorite story by Russell. It is called Plus X if I recall correctly. In it, one man disrupts an entire military complex of victorious aliens (victorious over Earth, that is) with merely his imagination and a piece of wire. Written with broad humor, it involves a pun and misdirection. I love it, my husband loves it, and my kids all loved it when I read it to them. He wrote an expanded version of it which does not have quite the punch of the original story, but is quite tolerable.

48baswood

John Roy Carlson - Cairo to Damascus.

"With the radical I was a radical, With the communist I was a pro communist, with the fascists, pro fascist; with the anti-Zionists, anti jewish. All these and many other roles I had assumed to survive"

John Roy Carlson was a pen name for Arthur Derounian who was an American free-lance investigative journalist. In 1943 he published Under Cover: My Four Years In the Nazi Underworld of America - 'The Amazing Revelation of How Axis Agents and Our Enemies Within are now Plotting to Destroy the United States'. His book was a best seller and so in 1947 he decided to use his contacts to infiltrate the fascist groups that were working in Cairo Egypt to train and finance the Arab volunteers who were launching a Jehad against the Jews in Palestine following the UN resolution to partition the country. Cairo to Damascus published in 1951 was the book resulting from his undercover activities. He arguably got closer to the action and a better understanding of the situation than the bus load of journalists covering the events who were working for various newspapers.

By the very nature of his task of spinning lies and disinformation to infiltrate and meet protagonists in a dangerous war torn situation, the reader might be suspicious that Derounian's writing is as much about the exploits of Derounian as the events that he describes. While this is true to a certain extent, because he explains in some detail the manoeuvres and tricks that he carried out to achieve his aims and the dangers to himself, he does not place himself above the events that he describes. His book is an important eye witness account of a dangerous conflict by an experienced journalist who developed sympathies to people on both sides in the struggle.

Derounian used previous contacts in the fascist underworld as well as his birthright as an Armenian to gain the confidence of the Arab volunteers, who were whipped up into a holy war against the Jews in Palestine. He managed to meet the movers and shakers in the two main volunteer groups; the Green shirts and the Muslim Brotherhood. When a brigade of the Green Shirts finally left Cairo, Derounian travelled with them as a photographer and sympathiser. The only way he could achieve this was to convince his compatriots that he was also extremely anti-Semitic. The Arabs were intent on killing as many Jews as possible at the behest of Allah. Derounian lived with the fighters in their advanced position outside the gates of Jerusalem and described the horrendous conditions under which they fought. They were a rag-tag of an army indisciplined, under prepared, unruly and lacking any sort of professionalism. They were both fanatical and cowardly, but Derounian grew to understand their passion and their hospitality and became attached to some of the individuals. The Arabs launched attacks against the Jewish Kibbutz outposts, which were at times spectacularly unsuccessful, but the Arabs had the numbers and were in a position to shell the new town of Jerusalem. Derounian was able to slip out into the Armenian quarter of the old town: The Vank and from their cross over to the Jewish side and talk his way into meeting the Jewish Haganah commanders. He stayed with them while they resisted the Arab onslaught of the Jewish part of Jerusalem and reported the inhabitants hardships, the hunger, the continuous bombardment and the grief over the dead. He managed to get back to the Armenian quarter to witness the Jewish Surrender.

At the end of the British Mandate the Arabs found themselves out fought by the much better armed and trained Israelis whose passion for their new country surpassed that of the Arab invaders, but Derounian himself was under increasing suspicion from both sides in the conflict and needed to get out fast, he then travelled to Bethlehem, Jericho, Amman and Damascus. In Damascus he managed to meet briefly with the Grand Mufti Haj Amin al-Hussein who was involved in financing and supporting the Arab movement. He also met with Nazi organisers and military advisers. He went onto Lebanon, before finely taking ship with Jewish refugees on their way to Israel, where he toured and experienced the Kibbutz movement at first hand. In 1948 he visited his birthplace now Alexandroupolis in Greece and was appalled by the poverty surrounding his old house before thankfully getting back to the United States.