thorold gives crowns and pounds and guineas in Q1 21

Questa conversazione è stata continuata da thorold goes from April to Shantih in Q2 21.

ConversazioniClub Read 2021

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

1thorold

Welcome to my first quarterly thread of 2021!

For those who don’t know me, I’m Mark, originally from the North of England, but I’ve been living in the Netherlands for most of my adult life. I retired from professional life a few years ago to spend more time with my books (and travelling, walking, and sailing: lets hope those activities become possible again soon!).

My reading interests are difficult to predict, but often guided to some extent by the quarterly themes of Reading Globally: this quarter we will be doing “small countries”.

This will be my sixth year in Club Read. My previous thread, Q4 2020, was here: https://www.librarything.com/topic/324906#

For those who don’t know me, I’m Mark, originally from the North of England, but I’ve been living in the Netherlands for most of my adult life. I retired from professional life a few years ago to spend more time with my books (and travelling, walking, and sailing: lets hope those activities become possible again soon!).

My reading interests are difficult to predict, but often guided to some extent by the quarterly themes of Reading Globally: this quarter we will be doing “small countries”.

This will be my sixth year in Club Read. My previous thread, Q4 2020, was here: https://www.librarything.com/topic/324906#

2thorold

When I was one-and-twenty

I heard a wise man say,

“Give crowns and pounds and guineas

But not your heart away;

Give pearls away and rubies

But keep your fancy free.”

But I was one-and-twenty,

No use to talk to me.

When I was one-and-twenty

I heard him say again,

“The heart out of the bosom

Was never given in vain;

’Tis paid with sighs a plenty

And sold for endless rue.”

And I am two-and-twenty,

And oh, ’tis true, ’tis true.

A E Housman, “When I was one and twenty”

3thorold

2020 Q4 stats:

I finished 59 books in Q4 (70 in Q1, 89 in Q2, 62 in Q3).

Author gender: M 43, F 16: 73% M ( Q1: 71% M; Q2: 69% M; Q3: 58% M)

Language: EN 40, NL 2, DE 5, FR 7, ES 4, IT 1 : 68% EN (Q1 54% EN; Q2 78% EN; Q3: 68% EN) — still more English than usual

Of the English books, 2 were translated from Swedish, 1 from Arabic, 5 from Russian

9 books (15%) were linked to the "Russians write revolutions" theme read (Q1: 28% "far right" theme; Q2 38% Southern Africa; Q3 24% travelling the TBR & 7% Southern Africa)

Publication dates from 1801 to 2020, mean 1975, median 1998; 13 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 0, physical books from the TBR 31, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 3, audiobooks 8, paid ebooks 9, other free/borrowed 8 — 53% from the TBR (Q1: 17% from the TBR, Q2: 61%; Q3: 63%)

47 unique first authors (1.26 books/author; Q1 1.11; Q2 1.15; Q3 1.31)

By gender: M 37, F 10 : 79% M (Q1 71% M ; Q2 71% M; Q3 64% M)

By main country: UK 17, US 5, NL 1, BE 1, FR 6, DE 1, AT 2, DDR 2, ES 1, SE 2, RU 4

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

30/9/2020 : 94 books (89465 book-days) (Change: 39 read, 39 added)

31/12/2020: 90 books (79128 book-days) (Change: 31 read, 27 added)

The average days per book has gone down to 879, 25% down from 1172 at the end of 2019, so I've been at least moderately successful in tackling the oldies. (Although the 2019 figure is slightly misleading because it didn't include any Christmas books!)

The oldest books currently on the TBR, all from June 2011, are: The letters of J. R. Ackerley, Birds without wings and De gevarendriehoek

Next after that is The Kellys and the O'Kellys, which is nine months younger.

Maybe I should aim to read at least one of the three oldest in Q1 :-)

I finished 59 books in Q4 (70 in Q1, 89 in Q2, 62 in Q3).

Author gender: M 43, F 16: 73% M ( Q1: 71% M; Q2: 69% M; Q3: 58% M)

Language: EN 40, NL 2, DE 5, FR 7, ES 4, IT 1 : 68% EN (Q1 54% EN; Q2 78% EN; Q3: 68% EN) — still more English than usual

Of the English books, 2 were translated from Swedish, 1 from Arabic, 5 from Russian

9 books (15%) were linked to the "Russians write revolutions" theme read (Q1: 28% "far right" theme; Q2 38% Southern Africa; Q3 24% travelling the TBR & 7% Southern Africa)

Publication dates from 1801 to 2020, mean 1975, median 1998; 13 books were published in the last five years.

Formats: library 0, physical books from the TBR 31, physical books from the main shelves (re-reads) 3, audiobooks 8, paid ebooks 9, other free/borrowed 8 — 53% from the TBR (Q1: 17% from the TBR, Q2: 61%; Q3: 63%)

47 unique first authors (1.26 books/author; Q1 1.11; Q2 1.15; Q3 1.31)

By gender: M 37, F 10 : 79% M (Q1 71% M ; Q2 71% M; Q3 64% M)

By main country: UK 17, US 5, NL 1, BE 1, FR 6, DE 1, AT 2, DDR 2, ES 1, SE 2, RU 4

TBR pile evolution:

22/12/2019 : 105 books (123090 book-days)

31/3/2020 : 110 books (129788 book-days) (Change: 14 read, 19 added)

30/6/2020 : 94 books (102188 book-days) (Change: 54 read, 48 added)

30/9/2020 : 94 books (89465 book-days) (Change: 39 read, 39 added)

31/12/2020: 90 books (79128 book-days) (Change: 31 read, 27 added)

The average days per book has gone down to 879, 25% down from 1172 at the end of 2019, so I've been at least moderately successful in tackling the oldies. (Although the 2019 figure is slightly misleading because it didn't include any Christmas books!)

The oldest books currently on the TBR, all from June 2011, are: The letters of J. R. Ackerley, Birds without wings and De gevarendriehoek

Next after that is The Kellys and the O'Kellys, which is nine months younger.

Maybe I should aim to read at least one of the three oldest in Q1 :-)

4thorold

2020 Overview

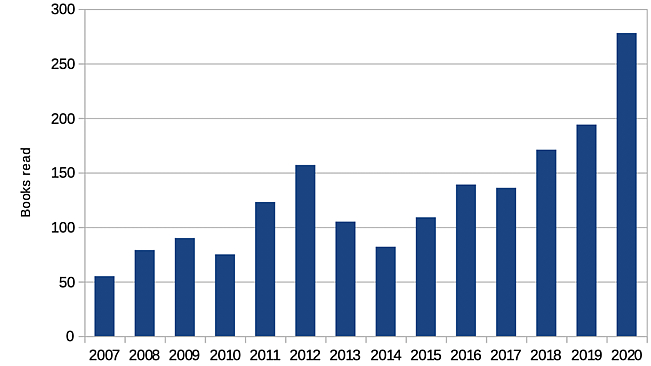

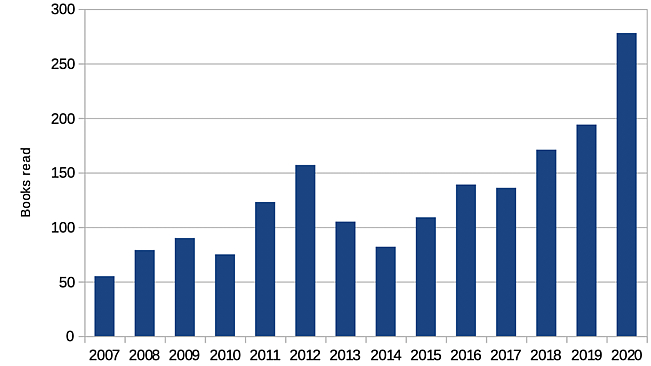

Club Read members seem to be divided about 80 : 20 between those who reacted to the stresses and practical demands of the year by reading far less than usual, and those like me who found themselves doing little other than reading...

I read 280 books in 2020, substantially more than in 2018 and 2019, which were both full years of retirement as well. I didn't count pages, but I read a few thick tomes from the older part of the TBR, so that was probably well over average as well.

Author gender: F 89, M 190, other 1 (68% M)

Language: 189 (67%) English, 24 (9%) Dutch, 24 (9%) German, 22 (8%) French, 13 (5%) Spanish, 7 (3%) Italian, 1.5 Afrikaans

(I'm counting Poppie as half Afrikaans, because I switched between the two versions)

Translations: 18 of the English books were translations, of which 6 were from Russian and the rest distributed between 9 other languages, including 3 books translated from languages I could have read in the original. One of the German books was a translation from Korean.

Authors: 214 unique authors (1.31 books/author): 153 M; 60 F; 1 Other (71% M)

Club Read members seem to be divided about 80 : 20 between those who reacted to the stresses and practical demands of the year by reading far less than usual, and those like me who found themselves doing little other than reading...

I read 280 books in 2020, substantially more than in 2018 and 2019, which were both full years of retirement as well. I didn't count pages, but I read a few thick tomes from the older part of the TBR, so that was probably well over average as well.

Author gender: F 89, M 190, other 1 (68% M)

Language: 189 (67%) English, 24 (9%) Dutch, 24 (9%) German, 22 (8%) French, 13 (5%) Spanish, 7 (3%) Italian, 1.5 Afrikaans

(I'm counting Poppie as half Afrikaans, because I switched between the two versions)

Translations: 18 of the English books were translations, of which 6 were from Russian and the rest distributed between 9 other languages, including 3 books translated from languages I could have read in the original. One of the German books was a translation from Korean.

Authors: 214 unique authors (1.31 books/author): 153 M; 60 F; 1 Other (71% M)

6thorold

2020 Themes

Despite the quantity, there wasn't all that much overall plan to 2020. There were the four quarterly Reading Globally topics, of which the one that took up most time was Southern Africa over the summer months (44 books). I have to say a big thank-you there to my South African friends for opening their shelves to me!

The Q1 read on the rise of the far right accounted for about 20 books, and Russians write revolutions in Q4 for 9 books.

Otherwise, the only real extended projects were my (re-)read of A S Byatt's fiction (16 books) and Schiller's dramas (counted as 9 books, although it was really 2 vols of the complete works). In the first half of the year I also completed my Zolathon (6 books in 2020); overall time for the Zolathon was 30 months, which according to the Guinness people would have been a record if I'd been wearing a Santa Claus costume and waterskiing as I read.

2021 Plans

Again, I'm expecting Reading Globally to play a big part. The themes coming up in 2021 are:

— January to March: Notes from a Small Population: 40+ places with under 500,000 inhabitants

— April to June: Childhood: Books for or about children in different cultures around the world

— July to September: The Lusophone world: writing from countries where Portuguese is or was an important language

— October-December: Translation prize winners

I've already started on a Liechtenstein novel, and I've got a couple of Icelanders lined up as well...

Other possible themes:

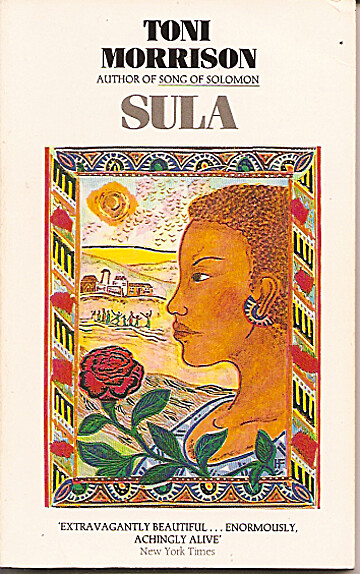

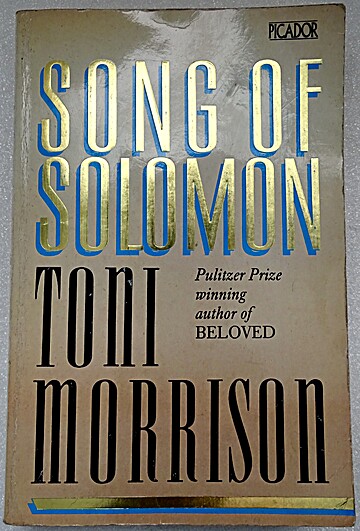

— I want to do another author read-through, as I did for Byatt. Current thinking (could still change) is to start with Toni Morrison, and possibly keep Byatt's little sister in reserve, depending on how much progress I make.

— Some sort of big saga: I was thinking about getting on with Het bureau, but I've now got a 900-page chunk of Muñoz Molina sitting on the TBR shelf, so maybe that's first!

— Focus on a poet: I'm thinking Coleridge, so it will probably end up being Heine

— Look out for mountains and possibly also for books-as-objects as non-fiction topics

Despite the quantity, there wasn't all that much overall plan to 2020. There were the four quarterly Reading Globally topics, of which the one that took up most time was Southern Africa over the summer months (44 books). I have to say a big thank-you there to my South African friends for opening their shelves to me!

The Q1 read on the rise of the far right accounted for about 20 books, and Russians write revolutions in Q4 for 9 books.

Otherwise, the only real extended projects were my (re-)read of A S Byatt's fiction (16 books) and Schiller's dramas (counted as 9 books, although it was really 2 vols of the complete works). In the first half of the year I also completed my Zolathon (6 books in 2020); overall time for the Zolathon was 30 months, which according to the Guinness people would have been a record if I'd been wearing a Santa Claus costume and waterskiing as I read.

2021 Plans

Again, I'm expecting Reading Globally to play a big part. The themes coming up in 2021 are:

— January to March: Notes from a Small Population: 40+ places with under 500,000 inhabitants

— April to June: Childhood: Books for or about children in different cultures around the world

— July to September: The Lusophone world: writing from countries where Portuguese is or was an important language

— October-December: Translation prize winners

I've already started on a Liechtenstein novel, and I've got a couple of Icelanders lined up as well...

Other possible themes:

— I want to do another author read-through, as I did for Byatt. Current thinking (could still change) is to start with Toni Morrison, and possibly keep Byatt's little sister in reserve, depending on how much progress I make.

— Some sort of big saga: I was thinking about getting on with Het bureau, but I've now got a 900-page chunk of Muñoz Molina sitting on the TBR shelf, so maybe that's first!

— Focus on a poet: I'm thinking Coleridge, so it will probably end up being Heine

— Look out for mountains and possibly also for books-as-objects as non-fiction topics

7dchaikin

Glad you stayed busy. Impressive year of reading. I'll try to keep up here this 2021. Happy New Year Mark.

8raton-liseur

>6 thorold: Lots of interesting themes! I'm sure following your thread will help lots ofus expand our reading horizons. Happy new litterary year!

9Dilara86

Happy New Year! Have you made your choices for your personal themes, or are you still mulling them over?

10thorold

>5 Dilara86: >7 dchaikin: >8 raton-liseur: >9 Dilara86: Thanks, all!

A bit more data, just for fun.

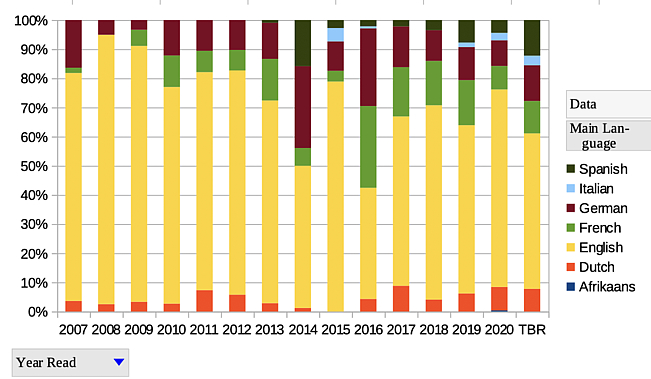

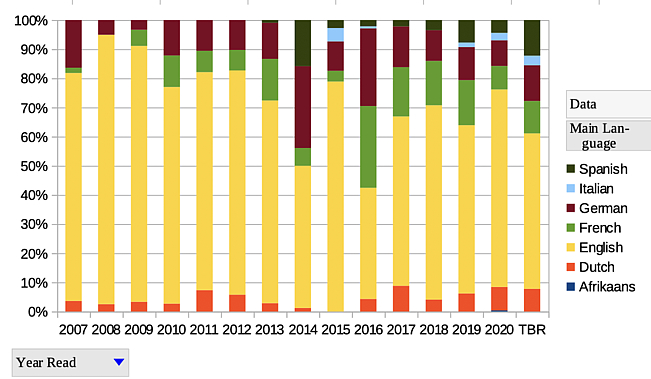

Languages

Here's the language breakdown of the books I've marked as read since 2007, as well as the TBR pile. Nothing if not inconsistent !

Over the whole period, English accounts for 67%, German 12%, French 11%, Dutch 5%, Spanish 4%, Italian 1%

Standing time

I looked a bit more closely at how long books stay on the pile. If I take all books marked as read since I joined LT, then 40% are books I added to LT on the same day I read them, i.e. they were ebooks, library books, or bypassed the TBR pile in some other way.

If I look only at physical books (read or on the TBR, but not including pre-LT books), then around 6% were read on the day they were added, 34% were read within a month, and 62% within a year. About 90% were read within five years of arriving on the pile.

(Rising to 97% within ten years, but that's not very good data, since I've only been recording dates for 13 years.)

On my current TBR pile (90 books), 12% are less than one month old, 46% less than one year, and 87% less than 5 years.

So I don't need to feel too guilty about my current TBR pile!

Book liberation

I haven't kept track of exact dates, but I've added 73 books to my "Deaccessioned" collection since late 2019, meaning I've given them away to friends or released them into the wild through Little Free Libraries. Probably a bit more than one a week, so not keeping pace with books added, but at least helping to reduce the chaos on the shelves a little. My rule now is that I don't put anything new on the fiction shelves unless there's a space for it. If necessary I create a space by discarding something nearby that I really don't need any more. With non-fiction I'm a little more reluctant to prune...

A bit more data, just for fun.

Languages

Here's the language breakdown of the books I've marked as read since 2007, as well as the TBR pile. Nothing if not inconsistent !

Over the whole period, English accounts for 67%, German 12%, French 11%, Dutch 5%, Spanish 4%, Italian 1%

Standing time

I looked a bit more closely at how long books stay on the pile. If I take all books marked as read since I joined LT, then 40% are books I added to LT on the same day I read them, i.e. they were ebooks, library books, or bypassed the TBR pile in some other way.

If I look only at physical books (read or on the TBR, but not including pre-LT books), then around 6% were read on the day they were added, 34% were read within a month, and 62% within a year. About 90% were read within five years of arriving on the pile.

(Rising to 97% within ten years, but that's not very good data, since I've only been recording dates for 13 years.)

On my current TBR pile (90 books), 12% are less than one month old, 46% less than one year, and 87% less than 5 years.

So I don't need to feel too guilty about my current TBR pile!

Book liberation

I haven't kept track of exact dates, but I've added 73 books to my "Deaccessioned" collection since late 2019, meaning I've given them away to friends or released them into the wild through Little Free Libraries. Probably a bit more than one a week, so not keeping pace with books added, but at least helping to reduce the chaos on the shelves a little. My rule now is that I don't put anything new on the fiction shelves unless there's a space for it. If necessary I create a space by discarding something nearby that I really don't need any more. With non-fiction I'm a little more reluctant to prune...

11ELiz_M

>10 thorold: "With non-fiction I'm a little more reluctant to prune..."

Hunh. I'd be the opposite (not that I read much non-fiction), assuming that most non-fiction is outdated within a few years of publishing (in some areas more than others - sciences, social sciences, for example). But a well-written story is still (more often than not) a good story.

Hunh. I'd be the opposite (not that I read much non-fiction), assuming that most non-fiction is outdated within a few years of publishing (in some areas more than others - sciences, social sciences, for example). But a well-written story is still (more often than not) a good story.

12thorold

>11 ELiz_M: Yes, you’re probably right! I’ve got a lot on the non-fiction shelves that any institutional library would have junked years ago (in fact, quite a bit of it actually was junked by institutional libraries...).

I think what’s behind my prejudice is that there’s a far bigger proportion of stuff on my fiction shelves that’s easily available elsewhere. The sort of non-fiction I go in for tends to be very expensive if new, and hard to find if old, whereas a big chunk of the fiction I’ve got is available from the library or in other inexpensive and rapid ways. Also, when you want to refer to a non-fiction book it’s normally a matter of just looking something up, you want it to be there instantly at arm’s length. When you want to re-read a novel, tomorrow or next week is usually OK too.

I think what’s behind my prejudice is that there’s a far bigger proportion of stuff on my fiction shelves that’s easily available elsewhere. The sort of non-fiction I go in for tends to be very expensive if new, and hard to find if old, whereas a big chunk of the fiction I’ve got is available from the library or in other inexpensive and rapid ways. Also, when you want to refer to a non-fiction book it’s normally a matter of just looking something up, you want it to be there instantly at arm’s length. When you want to re-read a novel, tomorrow or next week is usually OK too.

13AlisonY

Most interesting choice of themes for this year. I'm intrigued to see where you go with them.

14SassyLassy

>11 ELiz_M: While I would mostly agree about science, there are all those diaries, letters, memoirs (although I suppose a case could be made for them being partly fiction), not to mention different points of view that can help clarify the development of thinking about a topic over time, particularly in history or philosophy.

"...a well-written story is still (more often than not) a good story." Right you are!

>12 thorold: As usual, I will be following your year closely. Noting that your reading year is sort of in the same proportion to mine as cat lives are to humans.

"...when you want to refer to a non-fiction book it’s normally a matter of just looking something up, you want it to be there instantly at arm’s length" and it's oh so frustrating when it's not

"...a well-written story is still (more often than not) a good story." Right you are!

>12 thorold: As usual, I will be following your year closely. Noting that your reading year is sort of in the same proportion to mine as cat lives are to humans.

"...when you want to refer to a non-fiction book it’s normally a matter of just looking something up, you want it to be there instantly at arm’s length" and it's oh so frustrating when it's not

15dchaikin

>10 thorold: the yellow bar looks like it's trending smaller to me.

>12 thorold: (And >11 ELiz_M: ) - interesting to read this. I'll note that non-fiction books, excluding those that are really works of art, aren't typically something I want to reread end-to-end. Your comment about being able to look something up strikes home here.

>12 thorold: (And >11 ELiz_M: ) - interesting to read this. I'll note that non-fiction books, excluding those that are really works of art, aren't typically something I want to reread end-to-end. Your comment about being able to look something up strikes home here.

16AnnieMod

That's a lot of statistics for that early in the year ;) Always fun seeing what you are reading and I suspect we will also bump into each other a lot over in Reading Globally (especially in Q4 when I am hosting the quarterly thread...) :)

Happy new year!

Happy new year!

17thorold

First book of the year, and first for the "small countries" theme. Öhri's a Liechtensteiner who grew up in Ruggel and is president of the Liechtenstein writers' club, but now lives just over the border in Canton St Gallen. He's previously written a series of crime novels set in Bismarck's Berlin.

Liechtenstein - Roman einer Nation (2016) by Armin Öhri (Liechtenstein, 1978- )

This is one of those postmodern novels that is all about the adventures of a (fictional) writer with the same name as the author who is researching a book about a particular topic, and where you are kept guessing for a long time about what is going to turn out to be true and what fictional, rather like the things W G Sebald, Javier Cercas or Laurent Binet do. But with the additional twist that in this case the narrator is going through some kind of neurological illness as he's writing the book, so you're even less sure you can trust his experiences...

The narrator has been hired by a prominent Liechtenstein law firm to write a biography of the firm's founder, Wilhelm Anton Risch, conveniently born around 1920 to coincide with the re-launch of the sovereign state of Liechtenstein after the ruling family got kicked off their main estates in Czechoslovakia at the end of the First World War and had to move to the less cosy surroundings of their odd little land-holding in the upper Rhine valley. Risch experiences the disastrous floods of 1927, gets caught up in the fledgling Liechtenstein Nazi youth movement, has to go into exile after the abortive Putsch in March 1939, and serves in the German army during World War II. After the war he travels the world, spending time in the even smaller country of Nauru, then returns to Liechtenstein to practice law and manage trusts.

This gives Öhri plenty of scope to look at some of the less edifying aspects of Liechtenstein history in the 20th century, in particular the high incidence of selective memory loss among former Nazis (and their reluctance to let anyone write about national history), as well as a small selection of the most interesting financial scandals. Through Risch's daughter, he also finds space to tell us about the embarrassingly slow progress of the campaign to give women the vote — successful only after the third referendum, in 1984(!), when the proposition was passed by the narrowest of margins after a rare personal appeal to voters by the ruling prince. And the famous 2003 constitution, widely touted as the least democratic in Europe, which essentially gives the prince powers to do whatever he likes, regardless of voters or parliament.

But there are positive things as well: the pleasanter sides of living in a country where everyone knows everyone else's relatives. Öhri tells us a couple of times that the usual Liechtenstein enquiry to a stranger is "Wem Ghörst?" (Who are your folks?), and that the "Du" form is standard between Liechtensteiners. And the one reasonably positive story in Liechtenstein's history of international relations, when it was the only country in Western Europe to refuse Stalin's requests for forcible repatriation of Soviet citizens after World War II. A central episode in the early part of the book is the flight of the 500 men of General Smyslovsky's First Russian National Army, who had fought on the German side in the war, to seek asylum in Liechtenstein in May 1945. Öhri makes his character Risch a medical officer in Smyslovsky's force. It turns out that Öhri has a personal connection here: as a toddler he unwittingly photo-bombed the unveiling of a monument to the border-crossing of the Russians, and he reproduces the resulting charming snapshot of his younger self side-by-side with the general.

There's a strong Tintin flavour to the early career of Risch, at its most extreme when, aged 17, he is sent to Berlin as envoy of the Volksdeutsche youth movement in Liechtenstein, and he and his little dog are granted an audience with Hitler, but continuing with his journey across Russia and the Pacific (complete with shipwreck). It almost looks as though Öhri didn't notice he was doing this at first, then caught himself at it and decided to turn it into a joke against himself: his Russian chapter is called "Im Lande der Sowjets"!

Probably too many different things going on here to make a really strong novel, and all the characters apart from the country itself turn out to be rather elusive, but Öhri is a fluent and competent writer, and it reads like a good, page-turning crime thriller, postmodern flourishes notwithstanding.

Liechtenstein - Roman einer Nation (2016) by Armin Öhri (Liechtenstein, 1978- )

This is one of those postmodern novels that is all about the adventures of a (fictional) writer with the same name as the author who is researching a book about a particular topic, and where you are kept guessing for a long time about what is going to turn out to be true and what fictional, rather like the things W G Sebald, Javier Cercas or Laurent Binet do. But with the additional twist that in this case the narrator is going through some kind of neurological illness as he's writing the book, so you're even less sure you can trust his experiences...

The narrator has been hired by a prominent Liechtenstein law firm to write a biography of the firm's founder, Wilhelm Anton Risch, conveniently born around 1920 to coincide with the re-launch of the sovereign state of Liechtenstein after the ruling family got kicked off their main estates in Czechoslovakia at the end of the First World War and had to move to the less cosy surroundings of their odd little land-holding in the upper Rhine valley. Risch experiences the disastrous floods of 1927, gets caught up in the fledgling Liechtenstein Nazi youth movement, has to go into exile after the abortive Putsch in March 1939, and serves in the German army during World War II. After the war he travels the world, spending time in the even smaller country of Nauru, then returns to Liechtenstein to practice law and manage trusts.

This gives Öhri plenty of scope to look at some of the less edifying aspects of Liechtenstein history in the 20th century, in particular the high incidence of selective memory loss among former Nazis (and their reluctance to let anyone write about national history), as well as a small selection of the most interesting financial scandals. Through Risch's daughter, he also finds space to tell us about the embarrassingly slow progress of the campaign to give women the vote — successful only after the third referendum, in 1984(!), when the proposition was passed by the narrowest of margins after a rare personal appeal to voters by the ruling prince. And the famous 2003 constitution, widely touted as the least democratic in Europe, which essentially gives the prince powers to do whatever he likes, regardless of voters or parliament.

But there are positive things as well: the pleasanter sides of living in a country where everyone knows everyone else's relatives. Öhri tells us a couple of times that the usual Liechtenstein enquiry to a stranger is "Wem Ghörst?" (Who are your folks?), and that the "Du" form is standard between Liechtensteiners. And the one reasonably positive story in Liechtenstein's history of international relations, when it was the only country in Western Europe to refuse Stalin's requests for forcible repatriation of Soviet citizens after World War II. A central episode in the early part of the book is the flight of the 500 men of General Smyslovsky's First Russian National Army, who had fought on the German side in the war, to seek asylum in Liechtenstein in May 1945. Öhri makes his character Risch a medical officer in Smyslovsky's force. It turns out that Öhri has a personal connection here: as a toddler he unwittingly photo-bombed the unveiling of a monument to the border-crossing of the Russians, and he reproduces the resulting charming snapshot of his younger self side-by-side with the general.

There's a strong Tintin flavour to the early career of Risch, at its most extreme when, aged 17, he is sent to Berlin as envoy of the Volksdeutsche youth movement in Liechtenstein, and he and his little dog are granted an audience with Hitler, but continuing with his journey across Russia and the Pacific (complete with shipwreck). It almost looks as though Öhri didn't notice he was doing this at first, then caught himself at it and decided to turn it into a joke against himself: his Russian chapter is called "Im Lande der Sowjets"!

Probably too many different things going on here to make a really strong novel, and all the characters apart from the country itself turn out to be rather elusive, but Öhri is a fluent and competent writer, and it reads like a good, page-turning crime thriller, postmodern flourishes notwithstanding.

18baswood

Unsurprisingly you are the first to review or even own this book. I note you have got a couple of Icelandic novels coming up next can't be as unknown as the book from Liechtenstein. I do like the idea that most families know of each other in the country I can hear them saying ah the Ohri family they have a son who writes all the books.

19thorold

>18 baswood: they have a son who writes all the books

Probably more along the lines of "...who wrote that unforgivable book implying that we're all old Nazis and/or complicit in money-laundering"

Probably more along the lines of "...who wrote that unforgivable book implying that we're all old Nazis and/or complicit in money-laundering"

20ELiz_M

>12 thorold: Fair enough. And I had to laugh at many of your nonfiction books being decommissioned library books. :)

21thorold

Tying up loose ends, I realised that there was an audiobook I'd put aside three-quarters finished some weeks ago...

I've enjoyed several of Barnes's books, and I'm a Shostakovich fan, so this is one I've been curious to read since it come out.

The noise of time (2016) by Julian Barnes (UK, 1946- ) Audiobook, read by Daniel Philpott

Although it's framed as a biographical fiction about Shostakovich, that's almost a pretext: what Barnes is really interested in here is clearly the relationship between the creative artist and power. The artist may be a genius in his field, but he's still a human being, and not necessarily an exceptionally brave or reckless one. What does it do to him if he's confronted by threats and demands he doesn't have it in him to resist?

Shostakovich got a major ponck from Stalin after the opening of The Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District: after that he slowly worked his way out of official disfavour by compromising left, right and centre (or by ironically pretending to compromise: no-one quite knows, although plenty of people are still arguing about it), until he found himself being drawn uncomfortably close to power in the Khrushchev era.

Barnes tries to imagine what it might have been like to be inside Shostakovich's mind at those points. He doesn't really have any more evidence for that than we do, however, and he ends up with a character who is endearingly human and is undergoing the same kinds of fears and doubts that we might, but who somehow doesn't seem to have whatever it is about him that makes Shostakovich Shostakovich. We never get a real sense of him as someone whose life is built around music. In fact there's very little music in the book: most of the time, all that we hear is how other people have reacted to Shostakovich's music.

Interesting, but the effort Barnes must have put into researching this somehow seems disproportionate to the result.

---

I saw that someone else who reviewed the book recently wrote "Secondo me Barnes di musica non capisce niente". Hard to disagree...(https://www.librarything.com/review/148916362)

I've enjoyed several of Barnes's books, and I'm a Shostakovich fan, so this is one I've been curious to read since it come out.

The noise of time (2016) by Julian Barnes (UK, 1946- ) Audiobook, read by Daniel Philpott

Although it's framed as a biographical fiction about Shostakovich, that's almost a pretext: what Barnes is really interested in here is clearly the relationship between the creative artist and power. The artist may be a genius in his field, but he's still a human being, and not necessarily an exceptionally brave or reckless one. What does it do to him if he's confronted by threats and demands he doesn't have it in him to resist?

Shostakovich got a major ponck from Stalin after the opening of The Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District: after that he slowly worked his way out of official disfavour by compromising left, right and centre (or by ironically pretending to compromise: no-one quite knows, although plenty of people are still arguing about it), until he found himself being drawn uncomfortably close to power in the Khrushchev era.

Barnes tries to imagine what it might have been like to be inside Shostakovich's mind at those points. He doesn't really have any more evidence for that than we do, however, and he ends up with a character who is endearingly human and is undergoing the same kinds of fears and doubts that we might, but who somehow doesn't seem to have whatever it is about him that makes Shostakovich Shostakovich. We never get a real sense of him as someone whose life is built around music. In fact there's very little music in the book: most of the time, all that we hear is how other people have reacted to Shostakovich's music.

Interesting, but the effort Barnes must have put into researching this somehow seems disproportionate to the result.

---

I saw that someone else who reviewed the book recently wrote "Secondo me Barnes di musica non capisce niente". Hard to disagree...(https://www.librarything.com/review/148916362)

22tonikat

Lots of impressive numbers, both your analysis and of course your reading, no wonder i felt nowhere near your level of reading as you tick off title after title. And then there are the languages involved. Congratulations.

I think I may be finding my way clear to my commitment, but I'm not sure it will be anywhere near this.

I enjoyed reading of Shostakovich - I know a little of him but especially his observation on football teams under totalitarianism. It sounds like this is not the book to read more on.

I think I may be finding my way clear to my commitment, but I'm not sure it will be anywhere near this.

I enjoyed reading of Shostakovich - I know a little of him but especially his observation on football teams under totalitarianism. It sounds like this is not the book to read more on.

23thorold

>22 tonikat: Barnes brings in the football comment, of course!

It’s not a bad book, just disappointing if you’re looking for the composer. And to be fair, Barnes does end by telling readers who want a bio that they really ought to have been reading Shostakovich: a life remembered by Elizabeth Wilson.

It’s not a bad book, just disappointing if you’re looking for the composer. And to be fair, Barnes does end by telling readers who want a bio that they really ought to have been reading Shostakovich: a life remembered by Elizabeth Wilson.

24dchaikin

>19 thorold: (on >17 thorold: ) Probably more along the lines of "...who wrote that unforgivable book implying that we're all old Nazis and/or complicit in money-laundering"

That was my take home from the review! : ) Seriously, had no idea. I'm intrigued this country even exists.

>21 thorold: entertained by the review you quoted. Does seem strange to write about what's going on in a musician's mind without addressing the music...even if you're just imagining it.

That was my take home from the review! : ) Seriously, had no idea. I'm intrigued this country even exists.

>21 thorold: entertained by the review you quoted. Does seem strange to write about what's going on in a musician's mind without addressing the music...even if you're just imagining it.

25LolaWalser

Hello, hello!

Liechtenstein, Luxembourg--basically gated communities of the ultra-rich, surrounded by the merely very rich. How could fascism be absent... I do love the cover on this book though (my sole possession on the theme)

Liechtenstein, Luxembourg--basically gated communities of the ultra-rich, surrounded by the merely very rich. How could fascism be absent... I do love the cover on this book though (my sole possession on the theme)

26thorold

>25 LolaWalser: Fun! The cover photo of Öhri’s book is obviously meant as a parody of that style. He talks about Falz-Fein, too — apparently he was a Russian émigré who set up the first souvenir shop in Vaduz and generally founded the country’s tourist industry, inter alia bringing a German film company to Liechtenstein to film Paul Gallico’s Ludmila (Kinder der Berge, with Maximilian Schell).

27LolaWalser

>26 thorold:

Ha! I guess that answers the question "does everyone in Liechtenstein know everyone else in Liechtenstein".

Ha! I guess that answers the question "does everyone in Liechtenstein know everyone else in Liechtenstein".

28thorold

>27 LolaWalser: Yes, looks as though they probably do! I don't think Öhri quite manages to name all 40 000 of them in the space of 500 pages.

---

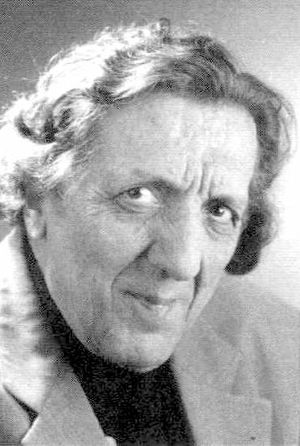

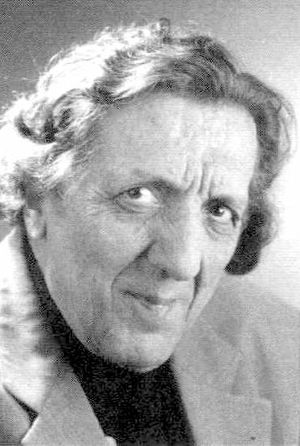

Something different again, a book from my Christmas pile tapping into my fondness for old sailing books. I hadn't heard of Ian Nicolson before, but he seems to have quite a stack of books on boatbuilding and sailing to his credit. He's a Scottish yacht-designer and -surveyor (the websites I checked all talk about him in the present tense, so I trust he's still with us: he must be in his early nineties by now).

The Ian Nicolson trilogy (1986, reprinted 2015) by Ian Nicolson (UK, ca. 1929 - )

(Author photo from Mylne Yachts)

This is a recent reprint of an omnibus edition of three of Nicolson's early, autobiographical books. It looks as though he must have revised the text slightly when they were put together in 1986, as there are little comments of a "that was then..." nature here and there, but for the most part they remain as originally written, reflecting the attitudes and practice of sixty years ago, very much before the age of the mass-produced white fibreglass bathtub.

Obviously the three books were never intended to be read together like this, as they all rather clumsily open with exactly the same literary trope, a short account of an exciting experience that has nothing to do with sailing, or with the rest of the book. Once is OK, twice is actually quite funny, but by the third time you're just thinking "this guy needs a competent editor!"

It is interesting to get Nicolson's viewpoint as a professional designer as well as an amateur sailor — he confesses at one point that he doesn't like the sea all that much, but he's fascinated by boats and how they behave and how to make them better. Of course, the downside of this is that he knows the people reading these books are potential clients: unlike most sailors he can't go around blaming the designer when something doesn't work as it should. Since sailing books run on accidents and emergencies, whenever something does go wrong he has to rely on weather, operator error, or undue haste to get the thing in the water at last.

The log of the Maken (published 1961), which opens with a dangerous high-speed drive to Dover in a pre-war Morgan three-wheeler, is an account of Nicolson's first long ocean cruise, in 1953-4, when he joined a couple of other young men to sail a 45-foot Norwegian ketch from Weymouth to Vancouver via the Panama Canal. As well as the sailing detail, it's interesting because of what it says about the world as it was then, still very much in the aftermath of World War II — when they call at the Canary Islands they get a string of requests from islanders and from German refugees who want to be smuggled to South America, for instance. By coincidence, it turns out that they arrive in the Caribbean at about the same time as Ann Davison on her solo Atlantic crossing (My ship is so small) — Nicolson mentions her, but they don't actually seem to have met.

Sea-Saint (1957) opens with the author skiing down a hill near Vancouver. He's been working in the design office of a Canadian shipyard for a while, and he's now ready to return to England. He hitch-hikes to the East coast in the space of a page and a half (calling on some friends in California on the way), and proceeds to look for a ship to take him home as crew from Nova Scotia. Nothing suitable seems to be on offer, but instead he finds a part-completed 30-foot wooden hull at a shipyard in Chester, south of Halifax, and works out that he's just about got enough money to have it finished and fitted out if he works on the job himself. The remainder of the book describes the process of construction of the St Elizabeth, the design decisions he made along the way, and his trip across the North Atlantic (solo, after a series of potential companions let him down at the last minute). Interesting to see how much his budget-driven minimalism overlaps with purists like Bernard Moitessier: for ocean cruising there's no point in burdening yourself with an engine or an anchor which you can't use anyway; electrics, fresh-water tanks and plumbed-in toilets are just extra things to go wrong, so they might as well be left out. Nova Scotia has canneries: he gets one of them to can a batch of tap-water for him! But there's also a lot about the pleasures of working with the Nova Scotia craftsmen at the yard, and the book gets a rather Arthur Ransome flavour when various local children start helping him on the job: they all get to ride along on the first day of his voyage, along the Nova Scotia coast.

Building the St Mary (1963) opens with a dangerous high-speed drive to Helensburgh in a Triumph sports car. The author clearly hasn't grown up much in the intervening years, he's still counting on speed (and strategically-placed mud) to prevent policemen from being able to make a note of his registration number. But it turns out that he's now married, a partner in a design practice in Glasgow with a charter business on the side, and he's in the process of building a successor to the St Elizabeth, which will be a 35-foot wooden ketch for use as a family cruiser. There's a similar blow-by-blow description of the design and construction process, again with a focus on practicality, low cost, and elimination of "gadgets". There's also a lot of very sixties whingeing about the reluctance of British suppliers actually to sell anything to anyone they haven't been dealing with for generations — or to deliver things once they have accepted an order. And some very colourful description of the complications of moving heavy objects around in small boatyards before the days when everyone had access to portable cranes and fork-lifts. The book ends with a description of the ship's maiden voyage, taking part in a Clyde Cruising Club race to Tobermory.

---

Something different again, a book from my Christmas pile tapping into my fondness for old sailing books. I hadn't heard of Ian Nicolson before, but he seems to have quite a stack of books on boatbuilding and sailing to his credit. He's a Scottish yacht-designer and -surveyor (the websites I checked all talk about him in the present tense, so I trust he's still with us: he must be in his early nineties by now).

The Ian Nicolson trilogy (1986, reprinted 2015) by Ian Nicolson (UK, ca. 1929 - )

(Author photo from Mylne Yachts)

This is a recent reprint of an omnibus edition of three of Nicolson's early, autobiographical books. It looks as though he must have revised the text slightly when they were put together in 1986, as there are little comments of a "that was then..." nature here and there, but for the most part they remain as originally written, reflecting the attitudes and practice of sixty years ago, very much before the age of the mass-produced white fibreglass bathtub.

Obviously the three books were never intended to be read together like this, as they all rather clumsily open with exactly the same literary trope, a short account of an exciting experience that has nothing to do with sailing, or with the rest of the book. Once is OK, twice is actually quite funny, but by the third time you're just thinking "this guy needs a competent editor!"

It is interesting to get Nicolson's viewpoint as a professional designer as well as an amateur sailor — he confesses at one point that he doesn't like the sea all that much, but he's fascinated by boats and how they behave and how to make them better. Of course, the downside of this is that he knows the people reading these books are potential clients: unlike most sailors he can't go around blaming the designer when something doesn't work as it should. Since sailing books run on accidents and emergencies, whenever something does go wrong he has to rely on weather, operator error, or undue haste to get the thing in the water at last.

The log of the Maken (published 1961), which opens with a dangerous high-speed drive to Dover in a pre-war Morgan three-wheeler, is an account of Nicolson's first long ocean cruise, in 1953-4, when he joined a couple of other young men to sail a 45-foot Norwegian ketch from Weymouth to Vancouver via the Panama Canal. As well as the sailing detail, it's interesting because of what it says about the world as it was then, still very much in the aftermath of World War II — when they call at the Canary Islands they get a string of requests from islanders and from German refugees who want to be smuggled to South America, for instance. By coincidence, it turns out that they arrive in the Caribbean at about the same time as Ann Davison on her solo Atlantic crossing (My ship is so small) — Nicolson mentions her, but they don't actually seem to have met.

Sea-Saint (1957) opens with the author skiing down a hill near Vancouver. He's been working in the design office of a Canadian shipyard for a while, and he's now ready to return to England. He hitch-hikes to the East coast in the space of a page and a half (calling on some friends in California on the way), and proceeds to look for a ship to take him home as crew from Nova Scotia. Nothing suitable seems to be on offer, but instead he finds a part-completed 30-foot wooden hull at a shipyard in Chester, south of Halifax, and works out that he's just about got enough money to have it finished and fitted out if he works on the job himself. The remainder of the book describes the process of construction of the St Elizabeth, the design decisions he made along the way, and his trip across the North Atlantic (solo, after a series of potential companions let him down at the last minute). Interesting to see how much his budget-driven minimalism overlaps with purists like Bernard Moitessier: for ocean cruising there's no point in burdening yourself with an engine or an anchor which you can't use anyway; electrics, fresh-water tanks and plumbed-in toilets are just extra things to go wrong, so they might as well be left out. Nova Scotia has canneries: he gets one of them to can a batch of tap-water for him! But there's also a lot about the pleasures of working with the Nova Scotia craftsmen at the yard, and the book gets a rather Arthur Ransome flavour when various local children start helping him on the job: they all get to ride along on the first day of his voyage, along the Nova Scotia coast.

Building the St Mary (1963) opens with a dangerous high-speed drive to Helensburgh in a Triumph sports car. The author clearly hasn't grown up much in the intervening years, he's still counting on speed (and strategically-placed mud) to prevent policemen from being able to make a note of his registration number. But it turns out that he's now married, a partner in a design practice in Glasgow with a charter business on the side, and he's in the process of building a successor to the St Elizabeth, which will be a 35-foot wooden ketch for use as a family cruiser. There's a similar blow-by-blow description of the design and construction process, again with a focus on practicality, low cost, and elimination of "gadgets". There's also a lot of very sixties whingeing about the reluctance of British suppliers actually to sell anything to anyone they haven't been dealing with for generations — or to deliver things once they have accepted an order. And some very colourful description of the complications of moving heavy objects around in small boatyards before the days when everyone had access to portable cranes and fork-lifts. The book ends with a description of the ship's maiden voyage, taking part in a Clyde Cruising Club race to Tobermory.

29rocketjk

>11 ELiz_M: & >12 thorold: It's funny, but I never think of . . . "most non-fiction {being} outdated within a few years of publishing (in some areas more than others - sciences, social sciences, for example)," although I do see the point. I often read older non-fiction because I like getting the perspective about the topic that looking through the lens of the passing of time can give. (In other words, knowing what biographers/researchers thought and wrote about a particular topic in, say, the 1950s is of interest to me, even if I know that there have been more recent research and discoveries made since that time.)

Anyway, I'm really just saying hello and Happy New Year and looking forward to another year of your interesting reading and reviewing. Cheers!

Anyway, I'm really just saying hello and Happy New Year and looking forward to another year of your interesting reading and reviewing. Cheers!

30AnnieMod

>11 ELiz_M:, >12 thorold:, >29 rocketjk:

While non-fiction may get outdated fast, it also gets referenced quite a lot in newer books - to the point where it actually makes sense to have the older book as well and read them in the order they came out. I had been reading a lot about pre-history in the last few years and that gets thrown on its head every time a new bone or a piece of shard is found, making the older books hopelessly outdated. And yet - any new author still references them - they are a shortcut to explain how radical the new discovery is.

While non-fiction may get outdated fast, it also gets referenced quite a lot in newer books - to the point where it actually makes sense to have the older book as well and read them in the order they came out. I had been reading a lot about pre-history in the last few years and that gets thrown on its head every time a new bone or a piece of shard is found, making the older books hopelessly outdated. And yet - any new author still references them - they are a shortcut to explain how radical the new discovery is.

31thorold

>30 AnnieMod: >29 rocketjk:

Yes, there are all sorts of different cases. If you’re a practicing lawyer or doctor, you subscribe to the online edition of the relevant textbooks, you don’t refer to your copy from college twenty years ago. If you’re a curious bookworm, you can often get more fun out of the old version than the current one, as Jerry says. >28 thorold: would be another good example: only masochists with huge amounts of time and/or money build wooden sailing boats for themselves nowadays, but it’s fascinating to look over the shoulders of someone doing it sixty years ago and hear why they did what they did.

Yes, there are all sorts of different cases. If you’re a practicing lawyer or doctor, you subscribe to the online edition of the relevant textbooks, you don’t refer to your copy from college twenty years ago. If you’re a curious bookworm, you can often get more fun out of the old version than the current one, as Jerry says. >28 thorold: would be another good example: only masochists with huge amounts of time and/or money build wooden sailing boats for themselves nowadays, but it’s fascinating to look over the shoulders of someone doing it sixty years ago and hear why they did what they did.

32thorold

>17 thorold: >25 LolaWalser: etc.

It doesn’t count for the “small nations” theme, of course, but reading about Liechtenstein made me want to watch The Mouse that roared again. Very silly, but rewarding: the fictitious Duchy of Grand Fenwick seems to be about half the land area of Nauru, and suffers from a limited gene-pool that makes about half the inhabitants look like Peter Sellers. And we get to see Jean Seberg romping around with a lot of men in chain-mail, just as she did in St Joan (See my 2020 thread), and there’s a moderately serious point about nuclear disarmament too, and a decrepit Southampton tugboat pretending to cross the Atlantic. Fun!

It doesn’t count for the “small nations” theme, of course, but reading about Liechtenstein made me want to watch The Mouse that roared again. Very silly, but rewarding: the fictitious Duchy of Grand Fenwick seems to be about half the land area of Nauru, and suffers from a limited gene-pool that makes about half the inhabitants look like Peter Sellers. And we get to see Jean Seberg romping around with a lot of men in chain-mail, just as she did in St Joan (See my 2020 thread), and there’s a moderately serious point about nuclear disarmament too, and a decrepit Southampton tugboat pretending to cross the Atlantic. Fun!

33LolaWalser

>32 thorold:

I mix up that one and The mouse that went to the moon hopelessly but yes and yes to both. Although I first flash to Margaret Rutherford, slightly tipsy, in full regalia on a horse, weaving through the honorary guard.

I mix up that one and The mouse that went to the moon hopelessly but yes and yes to both. Although I first flash to Margaret Rutherford, slightly tipsy, in full regalia on a horse, weaving through the honorary guard.

34rocketjk

>31 thorold: "If you’re a practicing lawyer or doctor, you subscribe to the online edition of the relevant textbooks, you don’t refer to your copy from college twenty years ago."

On a side note, when I owned my used bookstore, I'd often get folks who wanted to know if I would take their old nursing school or medical school textbooks from 20 years ago for store credit. Well, no. No, I wouldn't. Couldn't blame them for trying though, I guess.

On a side note, when I owned my used bookstore, I'd often get folks who wanted to know if I would take their old nursing school or medical school textbooks from 20 years ago for store credit. Well, no. No, I wouldn't. Couldn't blame them for trying though, I guess.

35sallypursell

Hi, thorold! Your reading stuns me, but I'll stop by off and on this year. Happy reading.

36thorold

>35 sallypursell: Hi! — Never forget that we're not on piecework here, it's enjoyment that counts, not quantity!

Two very short audiobooks that thrust themselves at me on Scribd. They make a nice bridge from Liechtenstein to Iceland, and just about covered my walk this morning between them:

Happísland: The short but not too brief tale of a Swiss spy in Iceland (2015) by Cédric H Roserens (Switzerland, 1974- )

Fantasviss: The Short but not too Brief Tale of an Icelandic Spy in Switzerland (2019) by Cédric H Roserens (Switzerland, 1974- )

both audiobooks, narrated by Angus Freathy

Roserens is a Swiss travel writer, originally from Martigny, who has lived in Iceland for some years. His books are self-published: he doesn't list a translator, so I assume he either writes them in English and French in parallel or translates them himself.

As the sub-titles imply, Happísland and Fantasviss are basically mirror-images of each other: in the first, the Swiss government, meeting secretly on the Rütli, has become concerned about Iceland overtaking it in an important "quality of life" index, and sends its top secret agent Hans-Üli Stauffacher to spend the year 2012 living undercover in Reykjavik. His monthly despatches to his controller (disguised as letters to his Mama) describe the weather and scenery, the strange things he is made to eat, and the advanced social security system; he tries to cope with the absence of cheese, public transport and vegetables, and he attends various local festivals.

In Fantasviss, it is a few years later, and Switzerland is creeping ahead again (after generous tax-advantages were granted by the federal government to the compiler of the "quality of life" index), so the Icelanders send out their top secret agent Sigurd Sig Sigurdsson ("Triple Sig") to check out the competition: he spends a month travelling around all twenty-six cantons (or, if you're pedantic, twenty cantons and six half-cantons) to discover the bizarre diversity of the Swiss, united only in their patriotic admiration of Roger Federer. He is puzzled by the scarcity of toponyms (most cantons seem to share a name with their main town and with the lake that it is on), by the complex inefficiencies of the health and education systems, the backwardness about women's rights, and so on, but impressed with the many interesting local dishes he gets to eat, the scenery, and the penknives. Asked to check up on the relevance of militarism to Switzerland's success, he learns that without soldiers the pubs would all be forced to close, and without army uniforms there would be no garment industry. He also discovers that the Swiss defeated the Burgundians in the fifteenth century by sneakily selling them penknives fitted with corkscrews...

The conclusion seems to be that the main advantage the Icelanders have over the Swiss is their low population density, whilst the Swiss profit from their more agreeable climate and their close links to the rest of Europe. We could probably have guessed that...

Entertaining, as far as it goes — they are only 45 minutes each on audio.

Two very short audiobooks that thrust themselves at me on Scribd. They make a nice bridge from Liechtenstein to Iceland, and just about covered my walk this morning between them:

Happísland: The short but not too brief tale of a Swiss spy in Iceland (2015) by Cédric H Roserens (Switzerland, 1974- )

Fantasviss: The Short but not too Brief Tale of an Icelandic Spy in Switzerland (2019) by Cédric H Roserens (Switzerland, 1974- )

both audiobooks, narrated by Angus Freathy

Roserens is a Swiss travel writer, originally from Martigny, who has lived in Iceland for some years. His books are self-published: he doesn't list a translator, so I assume he either writes them in English and French in parallel or translates them himself.

As the sub-titles imply, Happísland and Fantasviss are basically mirror-images of each other: in the first, the Swiss government, meeting secretly on the Rütli, has become concerned about Iceland overtaking it in an important "quality of life" index, and sends its top secret agent Hans-Üli Stauffacher to spend the year 2012 living undercover in Reykjavik. His monthly despatches to his controller (disguised as letters to his Mama) describe the weather and scenery, the strange things he is made to eat, and the advanced social security system; he tries to cope with the absence of cheese, public transport and vegetables, and he attends various local festivals.

In Fantasviss, it is a few years later, and Switzerland is creeping ahead again (after generous tax-advantages were granted by the federal government to the compiler of the "quality of life" index), so the Icelanders send out their top secret agent Sigurd Sig Sigurdsson ("Triple Sig") to check out the competition: he spends a month travelling around all twenty-six cantons (or, if you're pedantic, twenty cantons and six half-cantons) to discover the bizarre diversity of the Swiss, united only in their patriotic admiration of Roger Federer. He is puzzled by the scarcity of toponyms (most cantons seem to share a name with their main town and with the lake that it is on), by the complex inefficiencies of the health and education systems, the backwardness about women's rights, and so on, but impressed with the many interesting local dishes he gets to eat, the scenery, and the penknives. Asked to check up on the relevance of militarism to Switzerland's success, he learns that without soldiers the pubs would all be forced to close, and without army uniforms there would be no garment industry. He also discovers that the Swiss defeated the Burgundians in the fifteenth century by sneakily selling them penknives fitted with corkscrews...

The conclusion seems to be that the main advantage the Icelanders have over the Swiss is their low population density, whilst the Swiss profit from their more agreeable climate and their close links to the rest of Europe. We could probably have guessed that...

Entertaining, as far as it goes — they are only 45 minutes each on audio.

37rhian_of_oz

>36 thorold: These sound fun!

38LolaWalser

Sad to hear about the lack of cheese and veggies in Iceland. I had this occasional fantasy about freaking my family out by moving there.

39thorold

>38 LolaWalser: You could always live on skyr. Apart from that, it seems to be a choice between putrefied shark and sheep’s heads. (But that may be a tourist myth: characters in other books I’ve read about Iceland never eat at all, they appear to have adapted to a bio-ethanol diet.)

The other big problem seems to be a fictional-murder rate that is rapidly overtaking even notorious crime black-spots like Oxford, Ystad and Edinburgh. I suppose that would be a selling-point where freaking-out family members is concerned!

The other big problem seems to be a fictional-murder rate that is rapidly overtaking even notorious crime black-spots like Oxford, Ystad and Edinburgh. I suppose that would be a selling-point where freaking-out family members is concerned!

40thorold

Back to the "better late than never" department...

This has been recommended to me by numerous people (on LT and elsewhere) over the years, but I somehow never got to it until it was picked as our book club's January read. It also fits in very nicely with the German novel Herkunft by Saša Stanišic, which I read last year, and which is in some ways a 21st century continuation of Andrić's book. I struck a deal with Santa, and a copy turned up in my pile at just the right moment.

The 1961 Nobelist Ivo Andrić grew up in Sarajevo and Višegrad in Bosnia, a member of the generation of young radicals who assassinated the Archduke in 1914 (Andrić was in jail at the time, imprisoned by the Austrians for membership of a revolutionary group). He served as a Yugoslav diplomat between the wars, and was ambassador in Berlin in 1939. He's often counted as Yugoslavia's most important literary figure.

Lovett Edwards was a Canadian-born British journalist who reported from the Balkans before and during World War II; the success of his 1959 translation of The bridge on the Drina is presumed to have been largely responsible for bringing Andrić to the attention of the Nobel committee.

The bridge on the Drina (1945; English 1959) by Ivo Andrić (Yugoslavia, 1892-1975), translated by Lovett F Edwards (Canada, UK, 1901-1984)

Andrić takes us through the history of Bosnia from the early 16th century, when janissaries took a ten-year-old boy from his parents in a village near Višegrad. He would grow up to become the Ottoman statesman Mehmet Pasha and commission, as his pious legacy, the building of a stone bridge and a han at the point where he had been carried over the Višegrad ferry. In a series of vignettes, some linked, some not, we are taken through to 1914, when young people of the author's own generation are facing the opportunities of modern education and communications, and the challenges of the new political situation in the Balkans.

Although Andrić tells us a lot about the big things that are going on in the region over those four hundred years, everything is shown through the eyes of the ordinary people — Moslems, Serbs, and Jews; later also Austrians, Hungarians and Galicians — who live in the small town of Višegrad and meet to gossip on the bridge. History is experienced as a series of more or less inexplicable external events that affect their lives, it never seems to be anything they can influence themselves. Gruesome descriptions of arbitrary executions and tragic tales of suicide are mixed up with comic tales of romance and commercial intrigue, or with the minor tragedies of ordinary people's lives. The dignified conservative we see questioning reckless innovation in one story reappears in later ones as the last eccentric stick-in-the-mud holding on to the old ways against all reason, and the bridge constantly reappears as the structure that gives the stories a common thread.

Fascinating, absorbing, and an unusual way of looking at history: despite the long span of years covered it never loses its very human, very local feel: Andrić manages to make all these diverse characters from different cultures and ages into people we feel we know, somehow.

This has been recommended to me by numerous people (on LT and elsewhere) over the years, but I somehow never got to it until it was picked as our book club's January read. It also fits in very nicely with the German novel Herkunft by Saša Stanišic, which I read last year, and which is in some ways a 21st century continuation of Andrić's book. I struck a deal with Santa, and a copy turned up in my pile at just the right moment.

The 1961 Nobelist Ivo Andrić grew up in Sarajevo and Višegrad in Bosnia, a member of the generation of young radicals who assassinated the Archduke in 1914 (Andrić was in jail at the time, imprisoned by the Austrians for membership of a revolutionary group). He served as a Yugoslav diplomat between the wars, and was ambassador in Berlin in 1939. He's often counted as Yugoslavia's most important literary figure.

Lovett Edwards was a Canadian-born British journalist who reported from the Balkans before and during World War II; the success of his 1959 translation of The bridge on the Drina is presumed to have been largely responsible for bringing Andrić to the attention of the Nobel committee.

The bridge on the Drina (1945; English 1959) by Ivo Andrić (Yugoslavia, 1892-1975), translated by Lovett F Edwards (Canada, UK, 1901-1984)

Andrić takes us through the history of Bosnia from the early 16th century, when janissaries took a ten-year-old boy from his parents in a village near Višegrad. He would grow up to become the Ottoman statesman Mehmet Pasha and commission, as his pious legacy, the building of a stone bridge and a han at the point where he had been carried over the Višegrad ferry. In a series of vignettes, some linked, some not, we are taken through to 1914, when young people of the author's own generation are facing the opportunities of modern education and communications, and the challenges of the new political situation in the Balkans.

Although Andrić tells us a lot about the big things that are going on in the region over those four hundred years, everything is shown through the eyes of the ordinary people — Moslems, Serbs, and Jews; later also Austrians, Hungarians and Galicians — who live in the small town of Višegrad and meet to gossip on the bridge. History is experienced as a series of more or less inexplicable external events that affect their lives, it never seems to be anything they can influence themselves. Gruesome descriptions of arbitrary executions and tragic tales of suicide are mixed up with comic tales of romance and commercial intrigue, or with the minor tragedies of ordinary people's lives. The dignified conservative we see questioning reckless innovation in one story reappears in later ones as the last eccentric stick-in-the-mud holding on to the old ways against all reason, and the bridge constantly reappears as the structure that gives the stories a common thread.

Fascinating, absorbing, and an unusual way of looking at history: despite the long span of years covered it never loses its very human, very local feel: Andrić manages to make all these diverse characters from different cultures and ages into people we feel we know, somehow.

41AlisonY

>40 thorold: Oooh, that sounds really interesting - a great way to better understand the recent Bosnian conflict but through fiction. Onto the heaving list it goes.

42LolaWalser

>41 AlisonY:

I would just caution against drawing too linear conclusions between the war and this book. It's somewhat like trying to understand the Black Lives Matter protests based on, let's say, Uncle Tom's Cabin.

>40 thorold:

Nice review. I'd add, as a point of interest that is in itself illuminating about Bosnia, that Andric was an ethnic Croat. You mention Serbs, but there are almost three times more Croats in Bosnia than Serbs (mostly in Herzegovina, which is the region Croatia would like to annex off Bosnia, but also scattered around, including in larger cities like Sarajevo). Moreover, Andric was a Croat who was pro-Yugoslav (like Tito and, by definition, all Croatian Communists--and a fair chunk of liberals), someone who worked for the creation of a union of South Slavs (what "Yugoslavia" means), and on its constitution, served it as a diplomat.

As a corollary of this political choice--in those times, when a Serbian king headed the Yugoslav state--this Bosnian Croat wrote mostly in Serbian ekavian. And then continued after the proclamation of the Republic. Not uniformly--in the novels and other fiction various characters in the original are speaking their own dialects, so there's a mix of ekavian and Bosnian and Croatian ijekavian, and the stories set in Bosnia frequently have abundant Turkish markers. He wasn't the only one, but like Tito's choice to speak Serbian in public, in homage to the most populous Yugoslav ethnicity and its wartime sacrifices, it was a politically important choice. (It also likely made Andric THE ideal candidate for a Nobel, rather than it going to--the most often mentioned alternative--Miroslav Krleža, who was pro-Yugoslav but wrote in Croatian.)

Speaking of language... I'm always glad when people manage to enjoy Andric in English, because the translation must of necessity shear off half the magic of his complex linguistic tapestry. Consider, just as one example, the title itself. Contrary to the utter void and banality of the English "The bridge on Drina", the original Na Drini ćuprija whirls one like a flying carpet into another realm, of poetry, medievalism, and Oriental legend. "Ćuprija" is a Slavic modification of the Turkish köprü, itself a modification of Greek γέφῡρα (gephyra). So this word from the get go situates us specifically in Bosnia, where Slavs transformed Asia Minor as they were themselves being transformed from Christians to Muslims. The English "bridge" would correctly translate the usual word for the construction,"most"--but, obviously, there is no corresponding English "ćuprija".

And the word order itself is another sign of the unusual, another portal to somewhere else. In ordinary speech the phrase would be structured like the English translation--"ćuprija na Drini". Inverting the order into "On the Drina the (a) bridge", in the original makes it seem like a beginning of a poem or a song. Combined with the unusual and practically forgotten Turcism, there is a feeling of melancholy about the title such as, perhaps, in English might be achieved by using balladic Old English or some such.

And if this much is true for the title alone, just imagine how much more happens to the text. There is a bardic quality to this book which, I'm afraid, simply can't survive any translation.

Mind you, Andric had many registers and far from being his "typical" work, this is one of the more unusual. There are many other novels and stories and poems of his in standard language (often Serbian, but also Croatian),

Oh dear, I apologise deeply for the length of this. Please let me know if you'd rather I took it to my thread and just left a link!

I would just caution against drawing too linear conclusions between the war and this book. It's somewhat like trying to understand the Black Lives Matter protests based on, let's say, Uncle Tom's Cabin.

>40 thorold:

Nice review. I'd add, as a point of interest that is in itself illuminating about Bosnia, that Andric was an ethnic Croat. You mention Serbs, but there are almost three times more Croats in Bosnia than Serbs (mostly in Herzegovina, which is the region Croatia would like to annex off Bosnia, but also scattered around, including in larger cities like Sarajevo). Moreover, Andric was a Croat who was pro-Yugoslav (like Tito and, by definition, all Croatian Communists--and a fair chunk of liberals), someone who worked for the creation of a union of South Slavs (what "Yugoslavia" means), and on its constitution, served it as a diplomat.

As a corollary of this political choice--in those times, when a Serbian king headed the Yugoslav state--this Bosnian Croat wrote mostly in Serbian ekavian. And then continued after the proclamation of the Republic. Not uniformly--in the novels and other fiction various characters in the original are speaking their own dialects, so there's a mix of ekavian and Bosnian and Croatian ijekavian, and the stories set in Bosnia frequently have abundant Turkish markers. He wasn't the only one, but like Tito's choice to speak Serbian in public, in homage to the most populous Yugoslav ethnicity and its wartime sacrifices, it was a politically important choice. (It also likely made Andric THE ideal candidate for a Nobel, rather than it going to--the most often mentioned alternative--Miroslav Krleža, who was pro-Yugoslav but wrote in Croatian.)

Speaking of language... I'm always glad when people manage to enjoy Andric in English, because the translation must of necessity shear off half the magic of his complex linguistic tapestry. Consider, just as one example, the title itself. Contrary to the utter void and banality of the English "The bridge on Drina", the original Na Drini ćuprija whirls one like a flying carpet into another realm, of poetry, medievalism, and Oriental legend. "Ćuprija" is a Slavic modification of the Turkish köprü, itself a modification of Greek γέφῡρα (gephyra). So this word from the get go situates us specifically in Bosnia, where Slavs transformed Asia Minor as they were themselves being transformed from Christians to Muslims. The English "bridge" would correctly translate the usual word for the construction,"most"--but, obviously, there is no corresponding English "ćuprija".

And the word order itself is another sign of the unusual, another portal to somewhere else. In ordinary speech the phrase would be structured like the English translation--"ćuprija na Drini". Inverting the order into "On the Drina the (a) bridge", in the original makes it seem like a beginning of a poem or a song. Combined with the unusual and practically forgotten Turcism, there is a feeling of melancholy about the title such as, perhaps, in English might be achieved by using balladic Old English or some such.

And if this much is true for the title alone, just imagine how much more happens to the text. There is a bardic quality to this book which, I'm afraid, simply can't survive any translation.

Mind you, Andric had many registers and far from being his "typical" work, this is one of the more unusual. There are many other novels and stories and poems of his in standard language (often Serbian, but also Croatian),

Oh dear, I apologise deeply for the length of this. Please let me know if you'd rather I took it to my thread and just left a link!

43SassyLassy

>42 LolaWalser: Just finished this book on December 20th, in the same translation as >40 thorold:, so found your notes really useful, and a supplement to the introduction by William H McNeill and the translator's foreword, so thanks. I thought the translation worked well, but know that as with all translations it is only a taste of the real thing.

I was just trying to track a word back after finding a reference to "gopher wood", something that's unknown in the world of trees. However, there it is in the good old King James translation of Genesis, in reference to the material for Noah's ark. Wikipedia gives a reasonable explanation for the translation through various languages, all of which demonstrate your "linguistic tapestry". For the record, I'd come down on the side of kopher or pitched wood, if I was making a voyage like that!

I was just trying to track a word back after finding a reference to "gopher wood", something that's unknown in the world of trees. However, there it is in the good old King James translation of Genesis, in reference to the material for Noah's ark. Wikipedia gives a reasonable explanation for the translation through various languages, all of which demonstrate your "linguistic tapestry". For the record, I'd come down on the side of kopher or pitched wood, if I was making a voyage like that!

44AnnieMod

>40 thorold: I am so glad that you liked the novel.

When I first read it (let's not count the years), I did not know the word saga in the context of a multi-generational novel and that fits here. I've been calling it a novel about a place and a peoples.

I grew up on another river, next to another bridge with a lot of history in another city that had been there since the dawn of times. Not very unusual on the Balkans really :) But it gave me the connection I needed to appreciate the novel early enough in life.

When I first read it (let's not count the years), I did not know the word saga in the context of a multi-generational novel and that fits here. I've been calling it a novel about a place and a peoples.