Steven03tx's 2013 Reading Log - Vol. III

Questo è il seguito della conversazione Steven03tx's 2013 Reading Log - Vol. II.

Questa conversazione è stata continuata da StevenTX's 2013 Reading Log - Vol. IV.

ConversazioniClub Read 2013

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

Questa conversazione è attualmente segnalata come "addormentata"—l'ultimo messaggio è più vecchio di 90 giorni. Puoi rianimarla postando una risposta.

1StevenTX

On my Reading Shelf - Current and future reading

I've tried to structure my reading into categories with the vague goal of reading at least one book per category per month (with generous allowances for tomes). The books shown in larger size are the ones I'm actually reading at the moment.

Classics of Western Civilization

In chronological order and re-reading anything read more than 20 years ago

Science Fiction

A reading list based on the bibliography in Anatomy of Wonder and taken chronologically

Other

Includes Reading Globally, Author Theme Reads, Literary Centennials, and miscellaneous reading.

I've tried to structure my reading into categories with the vague goal of reading at least one book per category per month (with generous allowances for tomes). The books shown in larger size are the ones I'm actually reading at the moment.

Classics of Western Civilization

In chronological order and re-reading anything read more than 20 years ago

Science Fiction

A reading list based on the bibliography in Anatomy of Wonder and taken chronologically

Other

Includes Reading Globally, Author Theme Reads, Literary Centennials, and miscellaneous reading.

2StevenTX

Index to My 2013 Reading

(Book titles are touchstones that link to the work page. The date read is a link to my Club Read post.)

anonymous - Njál's Saga - February 10

- Lazarillo de Tormes - June 25

- The Homeric Hymns - August 23

Ackroyd, Peter - Hawksmoor - February 26

- London: The Biography - August 18

Antoni, Robert - As Flies to Whatless Boys - August 17

Arbuthnot, John et al. - Memoirs of the Extraordinary Life, Works, and Discoveries of Martinus Scriblerus - May 13

Bâ, Mariama - So Long a Letter - July 31

Bacon, Francis - New Atlantis - September 14

Balzac, Honoré de - Eugénie Grandet - March 9

- The Girl with the Golden Eyes - March 11

- A Harlot High and Low - February 21

Baxter, Stephen - The Time Ships - July 1

Bergerac, Cyrano de - Voyage to the Moon - September 22

Bernhard, Thomas - Correction - March 22

Blanchot, Maurice - Death Sentence - July 14

Brontë, Charlotte - Shirley - July 21

Burney, Fanny - Evelina - May 6

Campanella, Tommaso - The City of the Sun - September 13

Camus, Albert - The Myth of Sisyphus - July 7

Carpentier, Alejo - The Lost Steps - August 16

Cavendish, Margaret - The Blazing World - September 25

Coetzee, J. M. - Life & Times of Michael K - July 25

Conrad, Joseph - Under Western Eyes - March 17

Csáth, Géza - Opium and Other Stories - January 3

Dabija, Nicolae - Mierla Domesticita: Blackbird Once Wild, Now Tame - January 4

Davies, Norman - The Isles: A History - February 23

Deloney, Thomas - The Pleasant History of Thomas of Reading - May 6

De Quincey, Thomas - Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and Other Writings - September 8

Dickens, Charles - Hard Times - June 14

Diderot, Denis - The Nun - March 24

Duong Thu Huong - Paradise of the Blind - April 8

Duras, Marguerite - The Sea Wall - July 10

- Hiroshima Mon Amour - July 11

- The Sailor from Gibraltar - August 4

- India Song - August 13

Esquivel, Laura - Like Water for Chocolate - March 18

Ferguson, Will - 419 - July 28

Finley, Karen - Shock Treatment - August 23

Flude, Kevin - Divorced, Beheaded, Died... The History of Britain's Kings and Queens in Bite-Sized Chunks - May 25

Foigny, Gabriel de - The Southern Land, Known - September 29

Franzen, Jonathan - Freedom - July 20

Frayn, Michael - Skios - March 30

Gaskell, Elizabeth - Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life - March 13

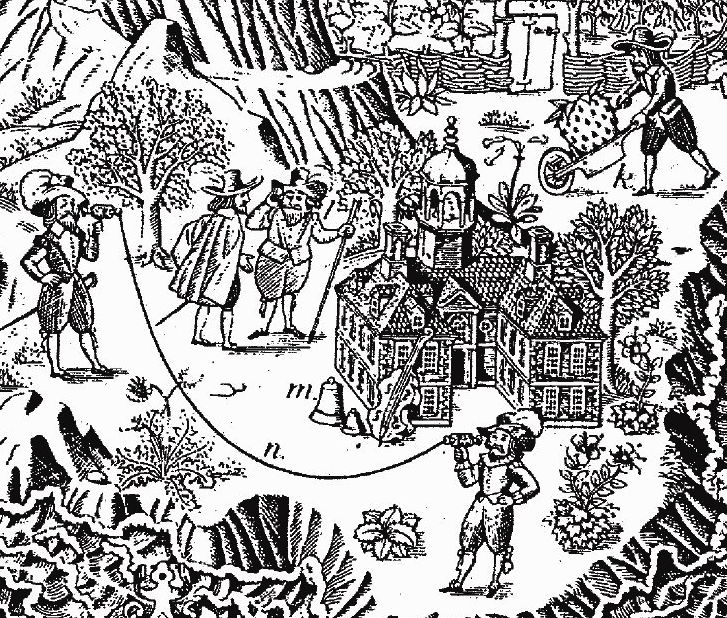

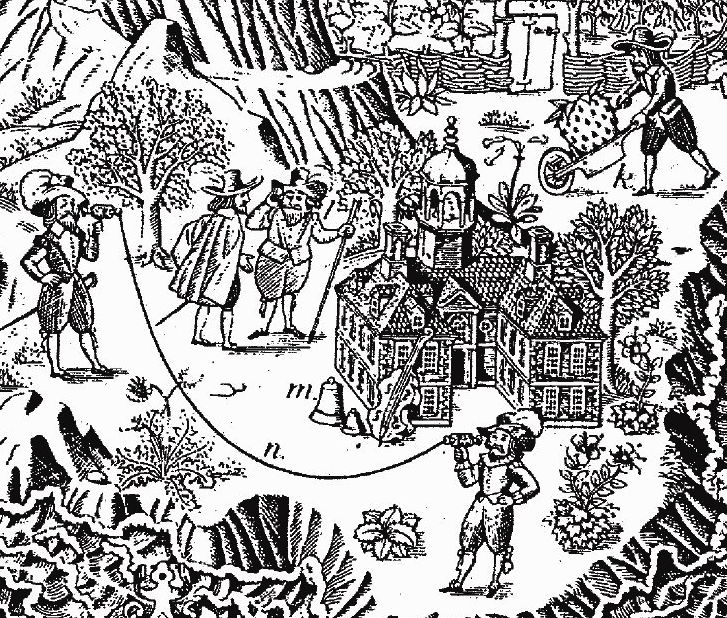

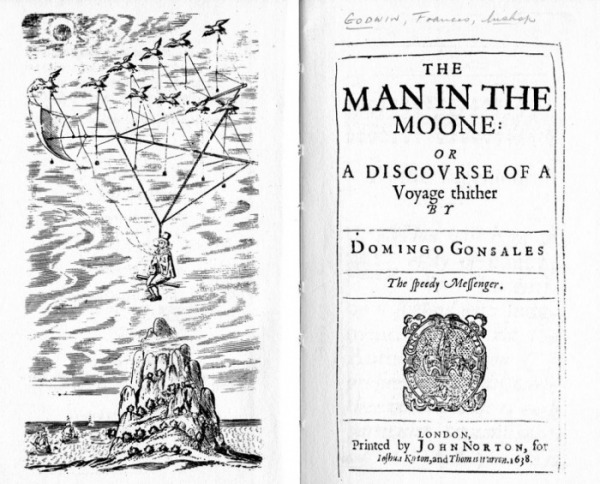

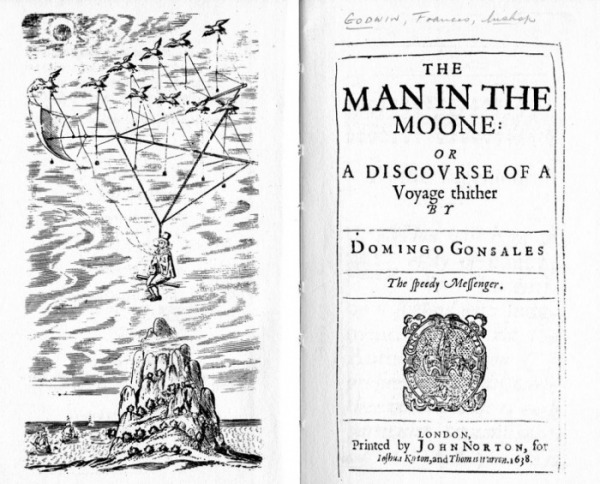

Godwin, Francis - The Man in the Moone - September 15

Gombrowicz, Witold - Ferdydurke - March 29

Grabinski, Stefan - The Dark Domain - March 19

Hernández, José - The Gaucho Martín Fierro - January 21

Hodgson, William Hope - The House on the Borderland - March 21

Hugo, Victor - The Toilers of the Sea - January 29

Jerome, Jerome K. - Three Men in a Boat - February 8

Johnson, Samuel - The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia - June 28

Kingsley, Charles - The Water-Babies - March 20

Kosmac, Ciril - A Day in Spring - March 17

Lee, Laurie - Cider with Rosie - April 23

L'Engle, Madeleine - A Wrinkle in Time - March 16

Leppin, Paul - The Road to Darkness - February 4

Lewis, Saunders - Monica - March 21

Lewis, Wyndham - Tarr - June 29

Lottman, Herbert R. - Albert Camus: A Biography - August 28

Lunch, Lydia - Paradoxia: A Predator's Diary - May 15 (no review)

MacDonald, George Phantastes - September 7

Mackenzie, Henry - The Man of Feeling - July 30

Maupassant, Guy de - A Life: The Humble Truth - March 31

- Bel-Ami - May 27

- Pierre et Jean - May 28

Miéville, China - Iron Council - April 24

More, Thomas - Utopia - September 13

Morgan, Kenneth O. - The Oxford History of Britain - April 9

Ondaatje, Michael - The English Patient - January 7

- The Cat's Table - April 16

Orwell, George - Animal Farm August 5

Pályi, András - Out of Oneself - January 9

Pelevin, Viktor - Omon Ra - May 4

Poe, Edgar Allan - Complete Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe - August 14

- The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket - August 20

Richardson, Dorothy M. - Pointed Roofs - May 7

- Backwater - May 30

- Honeycomb - July 4

- The Tunnel - September 18

- Interim - September 30

Roncagliolo, Santiago - Hi, This Is Conchita and Other Stories - April 6

Royle, Trevor - The Wars of the Roses: England's First Civil War - May 23

Sarduy, Severo - Firefly - January 13

Schnitzler, Arthur - Lieutenant Gustl - July 15

Scholder, Amy, et al. - Lust for Life: On the Writings of Kathy Acker - September 19

Scott, Sir Walter - Rob Roy - April 21

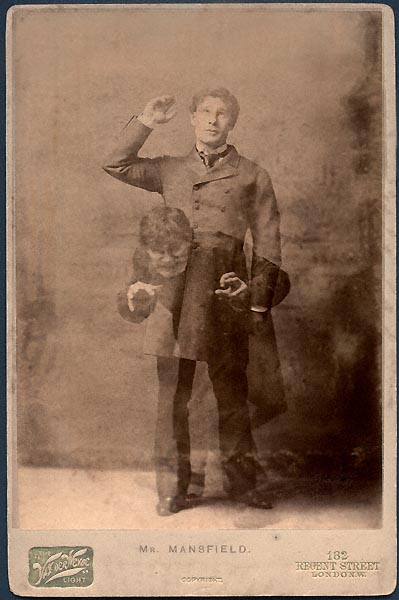

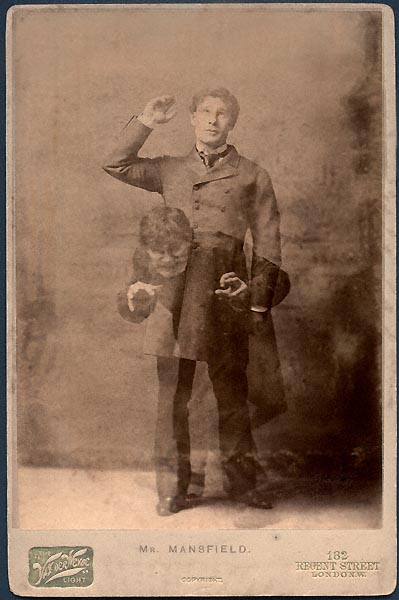

Stevenson, Robert Louis - Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde - August 6

Stewart, George R. - Earth Abides - April 29

Strindberg, August - The Ghost Sonata - April 18

Tolstaya, Tatyana - The Slynx - January 21

Verne, Jules - A Journey to the Centre of the Earth - May 26

Wang Anyi - The Song of Everlasting Sorrow - January 9

Waterfield, Robin - The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and the Sophists - September 20

Wells, H. G. - The Time Machine - May 9

- The War of the Worlds - June 21

Zola, Émile - The Kill - March 5

- La Reve (The Dream) - March 23

- Pot Luck - April 22

- The Ladies' Paradise - August 18

(Book titles are touchstones that link to the work page. The date read is a link to my Club Read post.)

anonymous - Njál's Saga - February 10

- Lazarillo de Tormes - June 25

- The Homeric Hymns - August 23

Ackroyd, Peter - Hawksmoor - February 26

- London: The Biography - August 18

Antoni, Robert - As Flies to Whatless Boys - August 17

Arbuthnot, John et al. - Memoirs of the Extraordinary Life, Works, and Discoveries of Martinus Scriblerus - May 13

Bâ, Mariama - So Long a Letter - July 31

Bacon, Francis - New Atlantis - September 14

Balzac, Honoré de - Eugénie Grandet - March 9

- The Girl with the Golden Eyes - March 11

- A Harlot High and Low - February 21

Baxter, Stephen - The Time Ships - July 1

Bergerac, Cyrano de - Voyage to the Moon - September 22

Bernhard, Thomas - Correction - March 22

Blanchot, Maurice - Death Sentence - July 14

Brontë, Charlotte - Shirley - July 21

Burney, Fanny - Evelina - May 6

Campanella, Tommaso - The City of the Sun - September 13

Camus, Albert - The Myth of Sisyphus - July 7

Carpentier, Alejo - The Lost Steps - August 16

Cavendish, Margaret - The Blazing World - September 25

Coetzee, J. M. - Life & Times of Michael K - July 25

Conrad, Joseph - Under Western Eyes - March 17

Csáth, Géza - Opium and Other Stories - January 3

Dabija, Nicolae - Mierla Domesticita: Blackbird Once Wild, Now Tame - January 4

Davies, Norman - The Isles: A History - February 23

Deloney, Thomas - The Pleasant History of Thomas of Reading - May 6

De Quincey, Thomas - Confessions of an English Opium-Eater and Other Writings - September 8

Dickens, Charles - Hard Times - June 14

Diderot, Denis - The Nun - March 24

Duong Thu Huong - Paradise of the Blind - April 8

Duras, Marguerite - The Sea Wall - July 10

- Hiroshima Mon Amour - July 11

- The Sailor from Gibraltar - August 4

- India Song - August 13

Esquivel, Laura - Like Water for Chocolate - March 18

Ferguson, Will - 419 - July 28

Finley, Karen - Shock Treatment - August 23

Flude, Kevin - Divorced, Beheaded, Died... The History of Britain's Kings and Queens in Bite-Sized Chunks - May 25

Foigny, Gabriel de - The Southern Land, Known - September 29

Franzen, Jonathan - Freedom - July 20

Frayn, Michael - Skios - March 30

Gaskell, Elizabeth - Mary Barton: A Tale of Manchester Life - March 13

Godwin, Francis - The Man in the Moone - September 15

Gombrowicz, Witold - Ferdydurke - March 29

Grabinski, Stefan - The Dark Domain - March 19

Hernández, José - The Gaucho Martín Fierro - January 21

Hodgson, William Hope - The House on the Borderland - March 21

Hugo, Victor - The Toilers of the Sea - January 29

Jerome, Jerome K. - Three Men in a Boat - February 8

Johnson, Samuel - The History of Rasselas, Prince of Abissinia - June 28

Kingsley, Charles - The Water-Babies - March 20

Kosmac, Ciril - A Day in Spring - March 17

Lee, Laurie - Cider with Rosie - April 23

L'Engle, Madeleine - A Wrinkle in Time - March 16

Leppin, Paul - The Road to Darkness - February 4

Lewis, Saunders - Monica - March 21

Lewis, Wyndham - Tarr - June 29

Lottman, Herbert R. - Albert Camus: A Biography - August 28

Lunch, Lydia - Paradoxia: A Predator's Diary - May 15 (no review)

MacDonald, George Phantastes - September 7

Mackenzie, Henry - The Man of Feeling - July 30

Maupassant, Guy de - A Life: The Humble Truth - March 31

- Bel-Ami - May 27

- Pierre et Jean - May 28

Miéville, China - Iron Council - April 24

More, Thomas - Utopia - September 13

Morgan, Kenneth O. - The Oxford History of Britain - April 9

Ondaatje, Michael - The English Patient - January 7

- The Cat's Table - April 16

Orwell, George - Animal Farm August 5

Pályi, András - Out of Oneself - January 9

Pelevin, Viktor - Omon Ra - May 4

Poe, Edgar Allan - Complete Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe - August 14

- The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket - August 20

Richardson, Dorothy M. - Pointed Roofs - May 7

- Backwater - May 30

- Honeycomb - July 4

- The Tunnel - September 18

- Interim - September 30

Roncagliolo, Santiago - Hi, This Is Conchita and Other Stories - April 6

Royle, Trevor - The Wars of the Roses: England's First Civil War - May 23

Sarduy, Severo - Firefly - January 13

Schnitzler, Arthur - Lieutenant Gustl - July 15

Scholder, Amy, et al. - Lust for Life: On the Writings of Kathy Acker - September 19

Scott, Sir Walter - Rob Roy - April 21

Stevenson, Robert Louis - Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde - August 6

Stewart, George R. - Earth Abides - April 29

Strindberg, August - The Ghost Sonata - April 18

Tolstaya, Tatyana - The Slynx - January 21

Verne, Jules - A Journey to the Centre of the Earth - May 26

Wang Anyi - The Song of Everlasting Sorrow - January 9

Waterfield, Robin - The First Philosophers: The Presocratics and the Sophists - September 20

Wells, H. G. - The Time Machine - May 9

- The War of the Worlds - June 21

Zola, Émile - The Kill - March 5

- La Reve (The Dream) - March 23

- Pot Luck - April 22

- The Ladies' Paradise - August 18

3StevenTX

2013 Statistics

Summary of Books Read

105 - books read

82 - novels

3 - plays and screenplays

7 - short story collections

2 - poetry collections

1 - mixed prose and verse collections

1 - epic verse

5 - history

1 - biography

2 - autobiography

2 - essay collections

1 - philosophy

Authors

83 - different authors

54 - authors new to me

77 - books by male authors

22 - books by female authors

4 - books by anonymous or unknown authors

4 - anthologies and books by multiple authors

Books Read by Author's Nationality

36 - English

21 - French

12 - American

5 - Scottish

3 - Polish

3 - Canadian

2 - Hungarian

2 - Russian

2 - Austrian

2 - Cuban

2 - Greek

1 - Moldovan

1 - Chinese

1 - Argentine

1 - Czech

1 - Icelandic

1 - Slovenian

1 - Welsh

1 - Mexican

1 - Peruvian

1 - Vietnamese

1 - Swedish

1 - Spanish

1 - South African

1 - Senegalese

1 - Trinidadian

1 - Italian

Books Read by Original Language

58 - English

22 - French

6 - Spanish

3 - German

2 - Hungarian

2 - Polish

2 - Russian

2 - Latin

2 - Greek

1 - Romanian

1 - Chinese

1 - Icelandic

1 - Slovenian

1 - Welsh

1 - Vietnamese

1 - Swedish

1 - Italian

Books Read by Decade of First Publication

2 - classical era

1 - 13th century

3 - 16th century

6 - 17th century

1 - 1740s

1 - 1750s

2 - 1770s

1 - 1790s

1 - 1810s

1 - 1820s

3 - 1830s

4 - 1840s

2 - 1850s

3 - 1860s

2 - 1870s

8 - 1880s

3 - 1890s

4 - 1900s

7 - 1910s

3 - 1920s

2 - 1930s

4 - 1940s

5 - 1950s

3 - 1960s

2 - 1970s

6 - 1980s

13 - 1990s

7 - 2000s

7 - 2010s

Summary of Books Read

105 - books read

82 - novels

3 - plays and screenplays

7 - short story collections

2 - poetry collections

1 - mixed prose and verse collections

1 - epic verse

5 - history

1 - biography

2 - autobiography

2 - essay collections

1 - philosophy

Authors

83 - different authors

54 - authors new to me

77 - books by male authors

22 - books by female authors

4 - books by anonymous or unknown authors

4 - anthologies and books by multiple authors

Books Read by Author's Nationality

36 - English

21 - French

12 - American

5 - Scottish

3 - Polish

3 - Canadian

2 - Hungarian

2 - Russian

2 - Austrian

2 - Cuban

2 - Greek

1 - Moldovan

1 - Chinese

1 - Argentine

1 - Czech

1 - Icelandic

1 - Slovenian

1 - Welsh

1 - Mexican

1 - Peruvian

1 - Vietnamese

1 - Swedish

1 - Spanish

1 - South African

1 - Senegalese

1 - Trinidadian

1 - Italian

Books Read by Original Language

58 - English

22 - French

6 - Spanish

3 - German

2 - Hungarian

2 - Polish

2 - Russian

2 - Latin

2 - Greek

1 - Romanian

1 - Chinese

1 - Icelandic

1 - Slovenian

1 - Welsh

1 - Vietnamese

1 - Swedish

1 - Italian

Books Read by Decade of First Publication

2 - classical era

1 - 13th century

3 - 16th century

6 - 17th century

1 - 1740s

1 - 1750s

2 - 1770s

1 - 1790s

1 - 1810s

1 - 1820s

3 - 1830s

4 - 1840s

2 - 1850s

3 - 1860s

2 - 1870s

8 - 1880s

3 - 1890s

4 - 1900s

7 - 1910s

3 - 1920s

2 - 1930s

4 - 1940s

5 - 1950s

3 - 1960s

2 - 1970s

6 - 1980s

13 - 1990s

7 - 2000s

7 - 2010s

4StevenTX

The Time Ships by Stephen Baxter

First published 1995

The Time Ships, a sequel to The Time Machine, was published 100 years after H. G. Wells's classic novel. The author, Stephen Baxter, copies Wells's style and tone, though the sequel is several times as long as the original and goes in a different direction thematically.

The story begins exactly where The Time Machine leaves off. The Time Traveler (whose name is still undisclosed) has returned from his journey to the distant future, has told his story to his unbelieving friends, and is about to disappear forever into the dimension of time. This time, however, he is speaking directly to the reader instead of through his amanuensis, the "Writer." His purpose in repeating his journey is to rescue the innocent Eloi woman Weena from the clutches of the evil Morlocks--her presumed fate after he lost track of her during his running battle with the Morlocks near the end of The Time Machine. Here, and not for the last time, we see the sensibilities of the 1990s intruding on a story based in the 1890s. To H. G. Wells's protagonist, Weena was little more than a semi-intelligent, adoring pet, and not the subject of romantic feelings.

After some hasty preparations, the Time Traveler once again sets forth into the the future. But he is soon dismayed to realize that the future into which he is traveling is not the world of the Eloi and Morlocks. It is a different future altogether, and it becomes more different the further he goes. He is left with the realization that his own actions in bringing back news of the distant future has changed the course of history itself. This leads, after more adventures in this new future, to an attempt to go back in time to keep himself from inventing the time machine in the first place and wreaking such havoc on history. But this attempt goes awry and leads to a further series of journeys forward and backward in time exploring the alternate pathways of Earth's history.

H. G. Wells used the original time machine to explore the idea that human society and the human organism were evolving together. He demonstrated how the division of the population into a leisure class and a working class could lead to the evolution of two incompatible cultures, and eventually two entirely different species. His novel also showcased recent scientific discoveries and theories about geological and stellar evolution, putting the history of mankind into the context of a larger, grander history of the universe itself.

Baxter's sequel does not develop Wells's social ideas, and he shows human evolution driven more by technology than economics. Instead the focus is more on the notion of causality and parallel realities. Any reader of science fiction is familiar with the paradox in which a traveler goes back in time and takes an action that prevents his own birth. Baxter's explanation is that this isn't a paradox at all, but the generation of new stream of reality that coexists with the old. So the tone of The Time Ships is much more technical than that of The Time Machine. There is also a bit of an anti-war theme, which it may have inherited from the 1960 movie in which Rod Taylor, as the Time Traveler, is dismayed to find a 20th century which seems perpetually at war. In one alternate history explored extensively in The Time Ships, World War I continues at least until the 1940s, and time travel itself becomes a weapon of war.

Though Baxter departs significantly from the predominate theme of The Time Machine, he does pay homage to H. G. Wells in one way. Throughout the The Time Ships the Time Traveler encounters mysterious apparitions of a being he calls "The Watcher." His physical description of this creature exactly matches that of the Martians in The War of the Worlds.

The Time Ships is an excellent and entertaining novel, but the focus on technology and scientific theories make it clearly part of the science fiction genre and of less interest to the general reader than H. G. Wells's The Time Machine. So while I would recommend it highly to any SF fan, it is not likely to interest those whose forays into SF are limited to the likes of Wells, Huxley and Orwell.

First published 1995

The Time Ships, a sequel to The Time Machine, was published 100 years after H. G. Wells's classic novel. The author, Stephen Baxter, copies Wells's style and tone, though the sequel is several times as long as the original and goes in a different direction thematically.

The story begins exactly where The Time Machine leaves off. The Time Traveler (whose name is still undisclosed) has returned from his journey to the distant future, has told his story to his unbelieving friends, and is about to disappear forever into the dimension of time. This time, however, he is speaking directly to the reader instead of through his amanuensis, the "Writer." His purpose in repeating his journey is to rescue the innocent Eloi woman Weena from the clutches of the evil Morlocks--her presumed fate after he lost track of her during his running battle with the Morlocks near the end of The Time Machine. Here, and not for the last time, we see the sensibilities of the 1990s intruding on a story based in the 1890s. To H. G. Wells's protagonist, Weena was little more than a semi-intelligent, adoring pet, and not the subject of romantic feelings.

After some hasty preparations, the Time Traveler once again sets forth into the the future. But he is soon dismayed to realize that the future into which he is traveling is not the world of the Eloi and Morlocks. It is a different future altogether, and it becomes more different the further he goes. He is left with the realization that his own actions in bringing back news of the distant future has changed the course of history itself. This leads, after more adventures in this new future, to an attempt to go back in time to keep himself from inventing the time machine in the first place and wreaking such havoc on history. But this attempt goes awry and leads to a further series of journeys forward and backward in time exploring the alternate pathways of Earth's history.

H. G. Wells used the original time machine to explore the idea that human society and the human organism were evolving together. He demonstrated how the division of the population into a leisure class and a working class could lead to the evolution of two incompatible cultures, and eventually two entirely different species. His novel also showcased recent scientific discoveries and theories about geological and stellar evolution, putting the history of mankind into the context of a larger, grander history of the universe itself.

Baxter's sequel does not develop Wells's social ideas, and he shows human evolution driven more by technology than economics. Instead the focus is more on the notion of causality and parallel realities. Any reader of science fiction is familiar with the paradox in which a traveler goes back in time and takes an action that prevents his own birth. Baxter's explanation is that this isn't a paradox at all, but the generation of new stream of reality that coexists with the old. So the tone of The Time Ships is much more technical than that of The Time Machine. There is also a bit of an anti-war theme, which it may have inherited from the 1960 movie in which Rod Taylor, as the Time Traveler, is dismayed to find a 20th century which seems perpetually at war. In one alternate history explored extensively in The Time Ships, World War I continues at least until the 1940s, and time travel itself becomes a weapon of war.

Though Baxter departs significantly from the predominate theme of The Time Machine, he does pay homage to H. G. Wells in one way. Throughout the The Time Ships the Time Traveler encounters mysterious apparitions of a being he calls "The Watcher." His physical description of this creature exactly matches that of the Martians in The War of the Worlds.

The Time Ships is an excellent and entertaining novel, but the focus on technology and scientific theories make it clearly part of the science fiction genre and of less interest to the general reader than H. G. Wells's The Time Machine. So while I would recommend it highly to any SF fan, it is not likely to interest those whose forays into SF are limited to the likes of Wells, Huxley and Orwell.

5StevenTX

There's an interesting parallel scenario in two of the novels I've read this year.

In Earth Abides by George R. Stewart a small, random group of people survive a global pandemic that wipes out all but a handful of the human race. They are faced with the task of surviving in an increasingly hostile and unpredictable world as the artifacts and conveniences of their civilization wear out or are used up.

In The Time Ships a band of time travelers is marooned in the pre-historic past with only a few damaged remnants of their technology. They must also try to survive in a world that is alien and hostile.

In each of these scenarios there is one individual who realizes that the key to survival is the retention of the attributes of civilization--scientific knowledge, political principles, cultural ideas--that will keep his companions from sliding backward into barbarism. He takes it upon himself to become a teacher and motivator. In one of these novels he succeeds; in the other he fails. And the one who fails is the one who had the greater time and resources at his disposal. So we have two contrasting views of human nature, one saying that knowledge alone can't lift a society above the level of sophistication dictated to it by economics and technology, the other saying it can.

In Earth Abides by George R. Stewart a small, random group of people survive a global pandemic that wipes out all but a handful of the human race. They are faced with the task of surviving in an increasingly hostile and unpredictable world as the artifacts and conveniences of their civilization wear out or are used up.

In The Time Ships a band of time travelers is marooned in the pre-historic past with only a few damaged remnants of their technology. They must also try to survive in a world that is alien and hostile.

In each of these scenarios there is one individual who realizes that the key to survival is the retention of the attributes of civilization--scientific knowledge, political principles, cultural ideas--that will keep his companions from sliding backward into barbarism. He takes it upon himself to become a teacher and motivator. In one of these novels he succeeds; in the other he fails. And the one who fails is the one who had the greater time and resources at his disposal. So we have two contrasting views of human nature, one saying that knowledge alone can't lift a society above the level of sophistication dictated to it by economics and technology, the other saying it can.

6JDHomrighausen

What an interesting reflection. Reminds me of the academic lifeboat competition. What cultural knowledge should survive?

8DieFledermaus

From your last thread - good review of Lazarillo de Tormes, I have that on the pile somewhere so will have to try to dig it out.

Also a tempting review of Rasselas. I've seen that one mentioned before but I think yours is the first review that made me want to read it.

Also a tempting review of Rasselas. I've seen that one mentioned before but I think yours is the first review that made me want to read it.

9rebeccanyc

I wasn't familiar with the academic lifeboat exercise, but these are certainly interesting topics to reflect on.

10StevenTX

Honeycomb by Dorothy Richardson

First published 1917

Third novel in the Pilgrimage sequence

"There was a life ahead that was going to enrich and change her as she had been enriched and changed by Hanover, but much more swiftly and intimately."

Miriam Henderson, the author's alter ego in her series of autobiographical novels, was raised a member of the gentry, but must seek employment because of her father's bankruptcy. After tutoring in Germany (which she loved) and teaching lower middle class girls in London (which she did not love), Miriam is now, in 1895, embarking on a career as a governess in a country home. It is an undemanding position with employers who are relaxed and companionable. But what is most important to Miriam, it is a life enriched by beautiful surroundings.

Aided by beauty (as she was by music in the first volume and books in the second), Miriam is finally able to transform herself from an insecure teenage girl to a mature, independent woman. "Beyond the horizon, gone away for ever into some outer darkness, were her old ideas of trouble, disease and death. Once they had always been quite near at hand, always ready to strike, laying cold hands on everything. They would return, but they would be changed. No need to fear them anymore."

Miriam's symbolic rite of passage into her independent adulthood--many modern readers will cringe at this--is when she first smokes a cigarette in front of others. It marks her not only as an adult, but as a woman of progressive, perhaps even radical, views. Indeed, Miriam is increasingly angered by the way the men around her treat women as their mental inferiors (and by the way the women acquiesce to it). Contemplating marriage, she says to herself:

"Men are all hard angry bones; always thinking something, only one thing at a time and unless that is agreed to, they murder. My husband shan't kill me . . . I'll shatter his conceited brow--make him see . . . two sides to every question . . . a million sides . . . no questions, only sides . . . always changing. Men argue, think they prove things; their foreheads recover--cool and calm. Damn them all--all men."

The ellipses in the above quote are in the original. Richardson uses them extensively in the stream of consciousness passages which are the bulk of the novel. Compared to the first two novels of Pilgrimage, Honeycomb is bolder in style, and the language is increasingly beautiful and rich in imagery. The themes of feminism and individuality are also more pronounced, making this Richardson's most rewarding and enjoyable novel yet.

Previous novels in Pilgrimage:

Pointed Roofs (1915)

Backwater (1916)

First published 1917

Third novel in the Pilgrimage sequence

"There was a life ahead that was going to enrich and change her as she had been enriched and changed by Hanover, but much more swiftly and intimately."

Miriam Henderson, the author's alter ego in her series of autobiographical novels, was raised a member of the gentry, but must seek employment because of her father's bankruptcy. After tutoring in Germany (which she loved) and teaching lower middle class girls in London (which she did not love), Miriam is now, in 1895, embarking on a career as a governess in a country home. It is an undemanding position with employers who are relaxed and companionable. But what is most important to Miriam, it is a life enriched by beautiful surroundings.

Aided by beauty (as she was by music in the first volume and books in the second), Miriam is finally able to transform herself from an insecure teenage girl to a mature, independent woman. "Beyond the horizon, gone away for ever into some outer darkness, were her old ideas of trouble, disease and death. Once they had always been quite near at hand, always ready to strike, laying cold hands on everything. They would return, but they would be changed. No need to fear them anymore."

Miriam's symbolic rite of passage into her independent adulthood--many modern readers will cringe at this--is when she first smokes a cigarette in front of others. It marks her not only as an adult, but as a woman of progressive, perhaps even radical, views. Indeed, Miriam is increasingly angered by the way the men around her treat women as their mental inferiors (and by the way the women acquiesce to it). Contemplating marriage, she says to herself:

"Men are all hard angry bones; always thinking something, only one thing at a time and unless that is agreed to, they murder. My husband shan't kill me . . . I'll shatter his conceited brow--make him see . . . two sides to every question . . . a million sides . . . no questions, only sides . . . always changing. Men argue, think they prove things; their foreheads recover--cool and calm. Damn them all--all men."

The ellipses in the above quote are in the original. Richardson uses them extensively in the stream of consciousness passages which are the bulk of the novel. Compared to the first two novels of Pilgrimage, Honeycomb is bolder in style, and the language is increasingly beautiful and rich in imagery. The themes of feminism and individuality are also more pronounced, making this Richardson's most rewarding and enjoyable novel yet.

Previous novels in Pilgrimage:

Pointed Roofs (1915)

Backwater (1916)

11StevenTX

The principal character in Honeycomb (see review above) makes an interesting observation based on her experience teaching the children of the poor and tutoring the children of the wealthy: The poor may not get a better education, but they get a more truthful one. Nothing has to be hidden from them, be it political theory, history or religion. They don't have to be protected from the truth or from hearing all sides of an issue. It isn't permissible, however, to teach rich kids things that will upset them or anger their parents. This was 1895. It may still be true to some extent today.

12NanaCC

I am intrigued by your review of Pilgrimage I. Did you enjoy the other two books as much as this one? I am adding to my wishlist.

13baswood

Excellent review of Honeycomb steven. I clicked on to the pilgrimage series and was amazed to find so few people with these books, especially the individual editions.

I am not so sure there are many governesses around today to teach the rich kids, however with more parents having an interest in what their children are taught in schools and in some cases having a say in the curriculum, then teachers might have to be very careful what they choose as subject matters for teaching.

I am not so sure there are many governesses around today to teach the rich kids, however with more parents having an interest in what their children are taught in schools and in some cases having a say in the curriculum, then teachers might have to be very careful what they choose as subject matters for teaching.

14StevenTX

#12 - I've enjoyed all three novels, but I thought Honeycomb was slightly the best so far because of the more practiced and picturesque writing style and the greater depth of theme.

#13 - I added the individual editions to my library as such so I could review them individually, but the series has been mostly published in four omnibus volumes. It looks like fewer than 40 members own the entire series (or have it wishlisted), though 129 own the first volume.

No, I don't suppose there are many governesses left, but at least where I live the rich tend to send their kids to private schools that are run by churches, so they get a more conservative education than the poorer kids who go to state-run public schools even if that wasn't the parents' intention when selecting the school. Which isn't to say that our state schools aren't heavily influenced by churches and conservative politicians, but at least they still teach Darwin, which most church-run schools wouldn't do.

It's interesting, too, that the protagonist in Honeycomb doesn't consult with her employers on what they want their children taught; she just makes the assumption that since they are wealthy and privileged it isn't safe for her to introduce egalitarian and socialist ideas or other progressive topics. This is similar to the way people avoid bearing bad news to persons in power, even if that person desperately needs and wants to hear such news as timely as possible. Wealth and power repel the truth even when there is no such intention on the part of the wealthy and powerful--I think this may be what Richardson is saying.

#13 - I added the individual editions to my library as such so I could review them individually, but the series has been mostly published in four omnibus volumes. It looks like fewer than 40 members own the entire series (or have it wishlisted), though 129 own the first volume.

No, I don't suppose there are many governesses left, but at least where I live the rich tend to send their kids to private schools that are run by churches, so they get a more conservative education than the poorer kids who go to state-run public schools even if that wasn't the parents' intention when selecting the school. Which isn't to say that our state schools aren't heavily influenced by churches and conservative politicians, but at least they still teach Darwin, which most church-run schools wouldn't do.

It's interesting, too, that the protagonist in Honeycomb doesn't consult with her employers on what they want their children taught; she just makes the assumption that since they are wealthy and privileged it isn't safe for her to introduce egalitarian and socialist ideas or other progressive topics. This is similar to the way people avoid bearing bad news to persons in power, even if that person desperately needs and wants to hear such news as timely as possible. Wealth and power repel the truth even when there is no such intention on the part of the wealthy and powerful--I think this may be what Richardson is saying.

15rebeccanyc

I think the whole issue of education of poorer kids is really complicated. For one thing, teachers are paid so little in the US that many teachers haven't studied extensively in the area they're teaching (this is especially true for the sciences, but also pertains to other areas). Further, since public schools are funded largely by property taxes (at least here in the northeast, although not in NYC itself), wealthier school districts can have nicer schools, smaller classrooms, more specialized teachers, etc., than poorer schools. Finally, if you lean towards conspiracy theory, as my sweetie does, it can be argued that the disinvestment in education in this country going back decades at this point is designed to keep the electorate, especially the poorer and more rural electorate, uninformed (so that they'll vote against their interests by voting for Republicans).

Interestingly, in NYC, many poor parents try to send their kids to parochial schools run by and subsidized by the Catholic church, even though they aren't Catholic themselves. They value the quality and seriousness of the education (and the keep the kids off the street aspect) and put up with the religious angle. However, the NYC archdiocese has been closing schools (and churches) because of their own not undeserved financial problems.

Interestingly, in NYC, many poor parents try to send their kids to parochial schools run by and subsidized by the Catholic church, even though they aren't Catholic themselves. They value the quality and seriousness of the education (and the keep the kids off the street aspect) and put up with the religious angle. However, the NYC archdiocese has been closing schools (and churches) because of their own not undeserved financial problems.

16mkboylan

14 Interesting comments on why the governess teaches the children as she does. Sounds logical to me, altho there have also been things written about the opposite behavior, i.e. working class nannies purposefully educating the children in the opposite direction from their parents. Interesting stuff.

Here is Sacramento, some research showed that teachers in lower income neighborhoods taught in a more authoritarian style while in better neighborhoods more democratic methods were used, teaching students how to think rather than memorize and spit out. Many of these teachers came from the same teaching school, where they were taught to use the democratic methods. When asked why they changed in the lower income schools, they said that they started out the other way but the students had no respect for them until they started behaving in a more authoritarian manner. Interesting stuff. This is not something they were doing on purpose - just everyone reacting according to their own socialization.

Here is Sacramento, some research showed that teachers in lower income neighborhoods taught in a more authoritarian style while in better neighborhoods more democratic methods were used, teaching students how to think rather than memorize and spit out. Many of these teachers came from the same teaching school, where they were taught to use the democratic methods. When asked why they changed in the lower income schools, they said that they started out the other way but the students had no respect for them until they started behaving in a more authoritarian manner. Interesting stuff. This is not something they were doing on purpose - just everyone reacting according to their own socialization.

17SassyLassy

>13 baswood: Part of the reason might be that they are difficult to find. I ordered Volume I from amazon after reading steven's review, only to receive an email about two weeks later telling me it was unobtainable. It wasn't available on other sites either. That would leave the second hand dealers, where there is a huge range of prices. It also leaves me wondering why amazon lists a book they can't get, when they are quite keen to let customers know there are "only two copies left" of other books. I will keep looking as I have enjoyed the reviews.

On equalities in American education, I would suggest reading Jonathan Kozol's Savage Inequalities: Children in America's Schools. It was written in the '90s, but I don't suspect things have gotten much better.

On equalities in American education, I would suggest reading Jonathan Kozol's Savage Inequalities: Children in America's Schools. It was written in the '90s, but I don't suspect things have gotten much better.

18StevenTX

The Myth of Sisyphus by Albert Camus

First published 1942

English translation by Justin O'Brien 1955

If there is no God--if life is finite, without meaning, and sometimes unbearable--why shouldn't we just commit suicide? This is the grim question with which Albert Camus begins his essay on the absurd. Camus rejects suicide, however, first by confronting the assumption "that refusing to grant a meaning to life necessarily leads to declaring that it is not worth living." A life that is acknowledged to be without meaning is, by his definition, an Absurd life. "Does the Absurd dictate death?" Camus argues that it does not.

The Absurd man knows that "seeking what is true is not seeking what is desirable," and will accept despair rather than "feed on the roses of illusion." He depends on his courage and his reasoning. He lives to experience life and to contemplate it free of the shackles of convention or guilt. Existence "is not a matter of explaining and solving, but of experiencing and describing." Life, the author says, "will be lived all the better if it has no meaning."

But does the Absurd man have the right "to behave badly without impunity?" Reassuringly, Camus answers that "The absurd does not liberate; it binds. It does not authorize all actions.... The absurd merely confers an equivalence on the consequences of those actions. It does not recommend crime, for that would be childish, but it restores to remorse its futility. Likewise, if all experiences are indifferent, that of duty is as legitimate as any other. One can be virtuous through a whim."

In making the above arguments, Camus draws on the work of other philosophers and novelists. He frequently cites Kierkegaard, Shestov and Nietzsche. Not having much background in philosophy, I found some of these passages hard to follow. But his references to the works of Dostoevsky and Kafka were very illuminating.

In his conclusion, Camus recounts the Greek myth of Sisyphus, the immortal who was condemned by the gods perpetually to roll a stone uphill, only to have it roll back just before reaching the summit. Sisyphus, he maintains, accepts that his position is hopeless, but scorns the gods by smiling as he retreats back down the hill to have another go at that rock. This revolt is his victory, for "there is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn." The Myth of Sisyphus is both profound and compelling. Even if it doesn't appeal to you as a personal philosophy, it wonderfully illuminates the literary works of Camus and many other modern writers.

Other works I have read by Albert Camus:

The Stranger

The Plague

First published 1942

English translation by Justin O'Brien 1955

If there is no God--if life is finite, without meaning, and sometimes unbearable--why shouldn't we just commit suicide? This is the grim question with which Albert Camus begins his essay on the absurd. Camus rejects suicide, however, first by confronting the assumption "that refusing to grant a meaning to life necessarily leads to declaring that it is not worth living." A life that is acknowledged to be without meaning is, by his definition, an Absurd life. "Does the Absurd dictate death?" Camus argues that it does not.

The Absurd man knows that "seeking what is true is not seeking what is desirable," and will accept despair rather than "feed on the roses of illusion." He depends on his courage and his reasoning. He lives to experience life and to contemplate it free of the shackles of convention or guilt. Existence "is not a matter of explaining and solving, but of experiencing and describing." Life, the author says, "will be lived all the better if it has no meaning."

But does the Absurd man have the right "to behave badly without impunity?" Reassuringly, Camus answers that "The absurd does not liberate; it binds. It does not authorize all actions.... The absurd merely confers an equivalence on the consequences of those actions. It does not recommend crime, for that would be childish, but it restores to remorse its futility. Likewise, if all experiences are indifferent, that of duty is as legitimate as any other. One can be virtuous through a whim."

In making the above arguments, Camus draws on the work of other philosophers and novelists. He frequently cites Kierkegaard, Shestov and Nietzsche. Not having much background in philosophy, I found some of these passages hard to follow. But his references to the works of Dostoevsky and Kafka were very illuminating.

In his conclusion, Camus recounts the Greek myth of Sisyphus, the immortal who was condemned by the gods perpetually to roll a stone uphill, only to have it roll back just before reaching the summit. Sisyphus, he maintains, accepts that his position is hopeless, but scorns the gods by smiling as he retreats back down the hill to have another go at that rock. This revolt is his victory, for "there is no fate that cannot be surmounted by scorn." The Myth of Sisyphus is both profound and compelling. Even if it doesn't appeal to you as a personal philosophy, it wonderfully illuminates the literary works of Camus and many other modern writers.

Other works I have read by Albert Camus:

The Stranger

The Plague

19kidzdoc

Fabulous review of The Myth of Sisyphus, Steven. I'm both eager and a bit reluctant to get to it, but I'll probably read it in September, along with The Stranger.

20SassyLassy

Great review. Oh how it takes me back. Part of me wants to reread it and part of me is afraid to, like doc. I

21JDHomrighausen

Enjoyed your Camus review.

Rebecca, you wrote: "Interestingly, in NYC, many poor parents try to send their kids to parochial schools run by and subsidized by the Catholic church, even though they aren't Catholic themselves."

The same is true near me, in San Francisco. SF public schools are so-so (unless you can get into Lowell). However, I suspect Catholic schools in SF are somewhat different from the ones in Texas...

Of course, everything in SF will melt down fast if CCSF closes.

Rebecca, you wrote: "Interestingly, in NYC, many poor parents try to send their kids to parochial schools run by and subsidized by the Catholic church, even though they aren't Catholic themselves."

The same is true near me, in San Francisco. SF public schools are so-so (unless you can get into Lowell). However, I suspect Catholic schools in SF are somewhat different from the ones in Texas...

Of course, everything in SF will melt down fast if CCSF closes.

22baswood

Great review of The Myth of Sisyphus Steven. That final essay on the myth of Sisyphus I found particularly enlightening. It is a wonderful essay,

23rebeccanyc

Jonathan, I think the schools in Texas Steven was referring to are probably mostly fundamentalist Protestant, not Catholic. But interesting about SF.

24StevenTX

In addition to regular parochial schools there are a number of non-parochial Catholic schools here that are extremely conservative. My sister sent her kids to one. But most of the the private schools are Southern Baptist, Church of Christ, etc. as Rebecca says.

26StevenTX

The Sea Wall by Marguerite Duras

First published 1950 as Un barrage contre le Pacifique

English translation by Herma Briffault

The Sea Wall is the first of three autobiographical novels Marguerite Duras would write about her teenage years in Indochina. She lived both in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) and on a small coastal rice plantation in what is now Cambodia. The latter is the setting for this novel.

The author's alter ego is named Suzanne. She lives with her mother, referred to only as "Ma," and her older brother Joseph. Ma and her husband had immigrated to Indochina in 1899, lured by the government's promise of easy wealth. The husband had died soon after Suzanne's birth. Later Ma had applied for a land concession, and been granted 100 acres of supposedly prime rice land. Too late, she had discovered that all but five acres of it was inundated by the sea every monsoon season. Ma had gone deeply into debt building a sea wall to keep out the salt water, only to see it collapse the very first year.

The story takes place in the early 1920s when Suzanne is 17, her brother 20. The trio are subsisting on wild game, fish, and the little rice they can manage to grow while Ma staves off her creditors and nurtures the hope of somehow rebuilding the sea wall. She pins her hopes on Suzanne, whose beauty is bound to attract a rich husband some day. Their dreams seem about to be realized when Monsieur Jo, the spoiled son of a wealthy colonist, falls in love with Suzanne. But he has no intention of marrying her, and Suzanne makes no secret of the fact that all they are after is his money.

The Sea Wall is a bleak novel. Its unlovable characters are condemned to poverty, not for lack of energy or ambition, but for a lack of vision. Ma doggedly fixates on the sea wall as her only hope and on marketing her daughter's virginity as the key to realizing it. Her two children think only of escape, but are incapable of breaking with the daily routine to find a way out.

The first half of the novel is sharply focused on the family and the affair with Monsieur Jo. In the second half, however, Duras broadens the vision to include the native population of the cities and countryside. There are gut wrenching scenes of poverty, disease, and injustice with the youngest being the ones who suffer the most. In addition to a tense family drama, the novel becomes a bitter indictment of colonialism.

Duras re-told the story of her youth in her most famous novel, The Lover, but with substantial changes in both plot and style. The Sea Wall more closely resembles the writing of Louis-Ferdinand Céline with its hard-boiled, grim and nihilistic tone.

Other works I have read by Marguerite Duras:

The Square

Moderato Cantabile

The Arternoon of Mr. Andesmas

Ten-Thirty on a Summer Night

(above four collected in Four Novels)

The Ravishing of Lol Stein

The Vice-Consul

Destroy, She Said

The Malady of Death

The Lover

First published 1950 as Un barrage contre le Pacifique

English translation by Herma Briffault

The Sea Wall is the first of three autobiographical novels Marguerite Duras would write about her teenage years in Indochina. She lived both in Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam) and on a small coastal rice plantation in what is now Cambodia. The latter is the setting for this novel.

The author's alter ego is named Suzanne. She lives with her mother, referred to only as "Ma," and her older brother Joseph. Ma and her husband had immigrated to Indochina in 1899, lured by the government's promise of easy wealth. The husband had died soon after Suzanne's birth. Later Ma had applied for a land concession, and been granted 100 acres of supposedly prime rice land. Too late, she had discovered that all but five acres of it was inundated by the sea every monsoon season. Ma had gone deeply into debt building a sea wall to keep out the salt water, only to see it collapse the very first year.

The story takes place in the early 1920s when Suzanne is 17, her brother 20. The trio are subsisting on wild game, fish, and the little rice they can manage to grow while Ma staves off her creditors and nurtures the hope of somehow rebuilding the sea wall. She pins her hopes on Suzanne, whose beauty is bound to attract a rich husband some day. Their dreams seem about to be realized when Monsieur Jo, the spoiled son of a wealthy colonist, falls in love with Suzanne. But he has no intention of marrying her, and Suzanne makes no secret of the fact that all they are after is his money.

The Sea Wall is a bleak novel. Its unlovable characters are condemned to poverty, not for lack of energy or ambition, but for a lack of vision. Ma doggedly fixates on the sea wall as her only hope and on marketing her daughter's virginity as the key to realizing it. Her two children think only of escape, but are incapable of breaking with the daily routine to find a way out.

The first half of the novel is sharply focused on the family and the affair with Monsieur Jo. In the second half, however, Duras broadens the vision to include the native population of the cities and countryside. There are gut wrenching scenes of poverty, disease, and injustice with the youngest being the ones who suffer the most. In addition to a tense family drama, the novel becomes a bitter indictment of colonialism.

Duras re-told the story of her youth in her most famous novel, The Lover, but with substantial changes in both plot and style. The Sea Wall more closely resembles the writing of Louis-Ferdinand Céline with its hard-boiled, grim and nihilistic tone.

Other works I have read by Marguerite Duras:

The Square

Moderato Cantabile

The Arternoon of Mr. Andesmas

Ten-Thirty on a Summer Night

(above four collected in Four Novels)

The Ravishing of Lol Stein

The Vice-Consul

Destroy, She Said

The Malady of Death

The Lover

27NanaCC

The Sea Wall sounds promising. I am adding to my wishlist.

28StevenTX

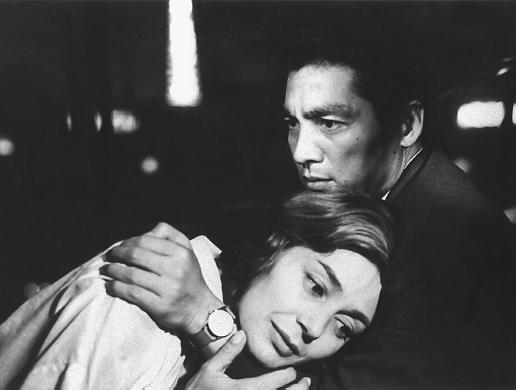

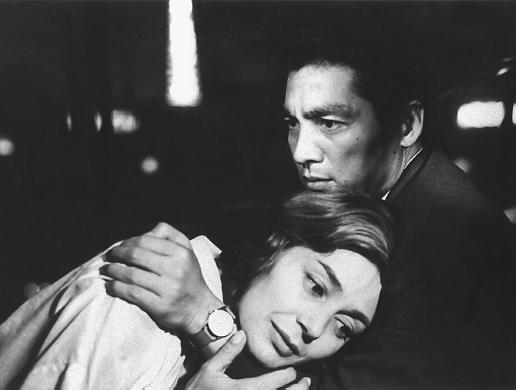

Hiroshima Mon Amour by Marguerite Duras

Screenplay with synopsis and notes by the author, as well as stills from the film

Filmed 1959, first published in book form 1960

Translated by Richard Seaver 1961

A French woman and a Japanese man meet in Hiroshima where the woman is playing a part in a film "about Peace." Though both are happily married, they fall in love with each other and spend the night together. In the morning she tells him she must leave Japan the following day, and they will never see one another again. "You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing," he tells her. "I saw everything. Everything," she insists. Their conversation is interwoven with horrific images of the atomic bomb and its aftermath.

As the day passes and the filming ends, the man persists in seeing the woman and extracting the details of a personal history that has made her suddenly so melancholy. During World War II in her native city of Nevers, she fell in love with a German soldier. As the Allies advanced upon the city the soldier made plans for her to escape to Bavaria with him, but on the day they were to leave he was shot by a resistance fighter. He died in her arms. She was accused of collaboration and had her head shaved. Insane with grief, she was locked in a cellar for months.

What this script does is give us two powerful images of war and its impact: the very public horror of Hiroshima, and the intense private tragedy of the woman of Nevers.

The book gives us Marguerite Duras's instructions to the director and background sketches on the characters. Frequently she gives options for how a scene should be shot or alternative dialogue, and footnotes tell us which choices the director, Alain Resnais, made. The numerous photographs are well-chosen to illustrate how her directions were implemented and they give a good feel for the film overall.

Screenplay with synopsis and notes by the author, as well as stills from the film

Filmed 1959, first published in book form 1960

Translated by Richard Seaver 1961

A French woman and a Japanese man meet in Hiroshima where the woman is playing a part in a film "about Peace." Though both are happily married, they fall in love with each other and spend the night together. In the morning she tells him she must leave Japan the following day, and they will never see one another again. "You saw nothing in Hiroshima. Nothing," he tells her. "I saw everything. Everything," she insists. Their conversation is interwoven with horrific images of the atomic bomb and its aftermath.

As the day passes and the filming ends, the man persists in seeing the woman and extracting the details of a personal history that has made her suddenly so melancholy. During World War II in her native city of Nevers, she fell in love with a German soldier. As the Allies advanced upon the city the soldier made plans for her to escape to Bavaria with him, but on the day they were to leave he was shot by a resistance fighter. He died in her arms. She was accused of collaboration and had her head shaved. Insane with grief, she was locked in a cellar for months.

What this script does is give us two powerful images of war and its impact: the very public horror of Hiroshima, and the intense private tragedy of the woman of Nevers.

The book gives us Marguerite Duras's instructions to the director and background sketches on the characters. Frequently she gives options for how a scene should be shot or alternative dialogue, and footnotes tell us which choices the director, Alain Resnais, made. The numerous photographs are well-chosen to illustrate how her directions were implemented and they give a good feel for the film overall.

30baswood

Excellent reviews of the Marguerite Duras books Steven. I have seen Hiroshima Mon Amour, but a very long time ago.

31StevenTX

Death Sentence by Maurice Blanchot

First published 1948 as L'Arrêt de Mort

English translation by Lydia Davis 1998

That the title of this novel is wonderfully, but differently, ambiguous in both French and English is highly indicative of its contents. "L'Arrêt de Mort" in French can mean both a legal judgment of death and the end of death. In English "Death Sentence" commonly also means a judgment of death, but it can also be construed to mean a written or spoken sentence that is about death. The fact that meaning is entirely dependent upon the interpretation of language, to the extent that our living and dying is dependent upon language, is interwoven throughout Blanchot's short novel.

The novel, written in the first person by an unnamed narrator, consists of two segments. In the first segment, taking place in 1938, the narrator tells of his relationship with a young woman named "J" who is dying of lung disease. J and the narrator discuss, among other things, her death, her suffering and her wish for suicide. At one point J's doctor insists on discontinuing her morphine shots because her condition is too frail. J screams at him, "If you don't kill me, you're a murderer." Ambiguous ideas about death and its meaning abound in this book. In reference to J's plea, the narrator says "Later I came across a similar phrase attributed to Kafka."

The second and longer segment of Death Sentence takes place in Paris during World War II, though the time and place may be of no significance. From the opening sentences, the narrator alerts us that the telling of the story is going to determine what the story is:

"I will go on with this story, but now I will take some precautions. I am not taking these precautions to cast a veil over the truth. The truth will be told, everything of importance that happened will be told. But not everything has yet happened....

"Even now, I am not sure that I am any more free than I was at the moment when I was not speaking. It may be that I am entirely mistaken. It may be that all these words are a curtain behind which what happened will never stop happening.... But a thought is not exactly a person, even if it lives and acts like one."

The events of this part of the novel, which involve encounters and conversations between the narrator and three different women, are dreamlike, discontinuous and enigmatic. The narrator's thoughts continue to be about death and suicide, but even more about language, silence and solitude. The language can be perplexing, but no less poetic: "...but this solitude has itself begun to speak, and I must in turn speak about this speaking solitude, not in derision, but because a greater solitude hovers above it, and above that solitude, another still greater, and each, taking the spoken word in order to smother and silence it, instead echoes it to infinity, and infinity becomes its echo."

I can't claim to understand everything Blanchot is saying in this novel, but it offers some intriguing interpretations. One is to consider it as metafiction with the narrator speaking, not as the author of a book, but as the book itself. For ideas live, change and develop in the mind, but as they are put into language and written down on paper their development ceases. In a manner of speaking, they die. Creation and death are the same, and language is what makes them so. In a postscript the author says, "These pages can end here, and . . . will remain until the very end. Whoever would obliterate it from me, in exchange for that end which I am searching for in vain, would himself become the beginning of my own story, and he would be my victim."

First published 1948 as L'Arrêt de Mort

English translation by Lydia Davis 1998

That the title of this novel is wonderfully, but differently, ambiguous in both French and English is highly indicative of its contents. "L'Arrêt de Mort" in French can mean both a legal judgment of death and the end of death. In English "Death Sentence" commonly also means a judgment of death, but it can also be construed to mean a written or spoken sentence that is about death. The fact that meaning is entirely dependent upon the interpretation of language, to the extent that our living and dying is dependent upon language, is interwoven throughout Blanchot's short novel.

The novel, written in the first person by an unnamed narrator, consists of two segments. In the first segment, taking place in 1938, the narrator tells of his relationship with a young woman named "J" who is dying of lung disease. J and the narrator discuss, among other things, her death, her suffering and her wish for suicide. At one point J's doctor insists on discontinuing her morphine shots because her condition is too frail. J screams at him, "If you don't kill me, you're a murderer." Ambiguous ideas about death and its meaning abound in this book. In reference to J's plea, the narrator says "Later I came across a similar phrase attributed to Kafka."

The second and longer segment of Death Sentence takes place in Paris during World War II, though the time and place may be of no significance. From the opening sentences, the narrator alerts us that the telling of the story is going to determine what the story is:

"I will go on with this story, but now I will take some precautions. I am not taking these precautions to cast a veil over the truth. The truth will be told, everything of importance that happened will be told. But not everything has yet happened....

"Even now, I am not sure that I am any more free than I was at the moment when I was not speaking. It may be that I am entirely mistaken. It may be that all these words are a curtain behind which what happened will never stop happening.... But a thought is not exactly a person, even if it lives and acts like one."

The events of this part of the novel, which involve encounters and conversations between the narrator and three different women, are dreamlike, discontinuous and enigmatic. The narrator's thoughts continue to be about death and suicide, but even more about language, silence and solitude. The language can be perplexing, but no less poetic: "...but this solitude has itself begun to speak, and I must in turn speak about this speaking solitude, not in derision, but because a greater solitude hovers above it, and above that solitude, another still greater, and each, taking the spoken word in order to smother and silence it, instead echoes it to infinity, and infinity becomes its echo."

I can't claim to understand everything Blanchot is saying in this novel, but it offers some intriguing interpretations. One is to consider it as metafiction with the narrator speaking, not as the author of a book, but as the book itself. For ideas live, change and develop in the mind, but as they are put into language and written down on paper their development ceases. In a manner of speaking, they die. Creation and death are the same, and language is what makes them so. In a postscript the author says, "These pages can end here, and . . . will remain until the very end. Whoever would obliterate it from me, in exchange for that end which I am searching for in vain, would himself become the beginning of my own story, and he would be my victim."

32kidzdoc

Nice reviews of the Duras novels and Death Sentence, Steven. I've added The Sea Wall to my wish list.

33SassyLassy

Maurice Blanchot is new to me I'm embarrassed to say after looking him up. This sounds like an intriguing novel, worth more than one reading. Thanks for the introduction to a new author and the thoughtful review.

34StevenTX

Lieutenant Gustl by Arthur Schniztler

First published 1900 or 1901 (sources disagree) as Leutnant Gustl

English translation by Richard L. Simon 2003

Previously translated as None but the Brave

Told entirely as a stream of consciousness, this short (59 pages) novella puts us in the title character's head for a period of several hours. Gustl is an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army out for a night's recreation in Vienna around the turn of the 20th century. He is attending a concert for which a fellow officer has given him a free ticket. "How long is this thing going to last?" is his first thought. In between checking out the girls in the box seats, he thinks ahead to the duel he will be fighting the next morning. He isn't worried; this isn't his first. Gustl's mind also wanders to the problem of the Jews--there are too many of them in the Army, he thinks.

Waiting in line at the coat check after the concert, eager to find that girl he thinks was giving him the eye, Gustl makes an impatient remark to the large man in front of him. The man turns, grabs the hilt of Gustl's sword with a powerful hand to keep him from drawing it, and calls the young lieutenant a fathead. Gustl is too stunned (or frightened?) to react as the man walks away. But it's now too late. He has been publicly shamed and did not retaliate. There is no way to recover from such a disgrace. As he blunders out into the night, Gustl realizes that the only honorable option is to commit suicide.

Gustl's rambling thoughts give us a compact but vivid picture of aspects of fin de siècle Viennese culture. The novel satirizes the army in particular with its self-destructive honor code, its tolerance of social and sexual escapades, and its pervasive antisemitism. There is also a sense of the fragility of human fate where a single word can destroy a life or reprieve it. Schnitzler was a trained psychologist, and his portrait of this young man is both convincing and entertaining. The use of stream of consciousness was ground-breaking, yet it's delightfully easy to read.

First published 1900 or 1901 (sources disagree) as Leutnant Gustl

English translation by Richard L. Simon 2003

Previously translated as None but the Brave

Told entirely as a stream of consciousness, this short (59 pages) novella puts us in the title character's head for a period of several hours. Gustl is an officer in the Austro-Hungarian army out for a night's recreation in Vienna around the turn of the 20th century. He is attending a concert for which a fellow officer has given him a free ticket. "How long is this thing going to last?" is his first thought. In between checking out the girls in the box seats, he thinks ahead to the duel he will be fighting the next morning. He isn't worried; this isn't his first. Gustl's mind also wanders to the problem of the Jews--there are too many of them in the Army, he thinks.

Waiting in line at the coat check after the concert, eager to find that girl he thinks was giving him the eye, Gustl makes an impatient remark to the large man in front of him. The man turns, grabs the hilt of Gustl's sword with a powerful hand to keep him from drawing it, and calls the young lieutenant a fathead. Gustl is too stunned (or frightened?) to react as the man walks away. But it's now too late. He has been publicly shamed and did not retaliate. There is no way to recover from such a disgrace. As he blunders out into the night, Gustl realizes that the only honorable option is to commit suicide.

Gustl's rambling thoughts give us a compact but vivid picture of aspects of fin de siècle Viennese culture. The novel satirizes the army in particular with its self-destructive honor code, its tolerance of social and sexual escapades, and its pervasive antisemitism. There is also a sense of the fragility of human fate where a single word can destroy a life or reprieve it. Schnitzler was a trained psychologist, and his portrait of this young man is both convincing and entertaining. The use of stream of consciousness was ground-breaking, yet it's delightfully easy to read.

35edwinbcn

Glad you enjoyed Lieutenant Gustl, Steven. I did not think many people were going to read that, but I suppose it's on the 1001 list.

36rebeccanyc

Death Sentence sounds so . . . French, I guess! Not sure that's one for me, or the Schnitzler either, but I enjoyed reading about both these unfamiliar (to me) authors.

37mkboylan

Lieutenant Gustl sounds like an example of one of those occasions where we limit male behavior to a stereotype that is so often overlooked. (I mean the fact that we talk a lot about how we limit female behavior, but not as much as we talk about how we limit male behavior and HOW THAT IS HARMFUL.

38zenomax

Death Sentence sounds quite intriguing. Like SassyLassy I had never heard of Blanchot, but I mean to rectify that.

39kidzdoc

Nice review of Lieutenant Gustl, Steven. I looked for a free e-book of it, but I could only find the German edition of it. Where did you get your copy of it?

40baswood

Great reviews of Death Sentence and Lieutenant Gustl. Particularly interested by the Schnitzler book and curious as to why there has been a modern translation,

41StevenTX

#39 - I purchased it new from Amazon two years ago. It looks like it's out of print now. They have used copies, but it's rather expensive for such a tiny book.

There are several collections of Schnitzler's stories and novellas in print, but as far as I can tell none of them contains Lieutenant Gustl. His major work is a novel The Road into the Open, but his most well-known piece is the novella Dream Story because it was the basis (very loosely, I suspect) of the Kubrick film "Eyes Wide Shut."

There are several collections of Schnitzler's stories and novellas in print, but as far as I can tell none of them contains Lieutenant Gustl. His major work is a novel The Road into the Open, but his most well-known piece is the novella Dream Story because it was the basis (very loosely, I suspect) of the Kubrick film "Eyes Wide Shut."

42LolaWalser

There's at least one earlier famous film based on a Schnitzler story--Max Ophuls' La ronde. Beautiful movie. (Won't sit well with prudes--concerns linked sexual affairs, with a person from one encounter continuing into another with a new partner, until the "chain" completes into a circle.)

Schnitzler is (or was, or ought to be) known well enough even in the Anglo world that the historian Peter Gay titled one of his books Schnitzler's Century. He is the first writer of the sunset of Austro-Hungary; stylistically innovative (the inner monologue in this novella predates Anglo modernism), anticipating all the great themes of the 20th century--neuroses sexual and historical, antisemitic savagery, modern anguishes of every kind.

Gustl's story is about the death of the Austro-Hungarian empire, sclerotically incapable of transformation into anything but dust. An officer but not a high-born aristocrat, Gustl is the victim of the caste system that trained him to ape the style of the long-dead aristocracy, in military dressage to love affairs to how one responds to insults. He is a relic of a strange kind--a counterfeit relic, just like Austro-Hungary had become a counterfeit empire. The middle class, the petty bourgeois, the city, the parliament, the businessmen, the financiers, had long burst the confines of the medieval hierarchies, had emptied them of real meaning. You think you're a prince because you were taught to imitate princes, then a shopkeeper comes along and calls you a dumb kid--and you see yourself for the first time in your life for what you really are--what everyone else can see you are. A useless dumbbell, a dunce fed on fairy tales, a fake with a code of honour but no right to that honour.

It's interesting how often this theme is taken up by precisely Austrian Jewish writers. Aristocracy, aristocratic mode of being was explicitly out of bounds for Jews, and yet all education was based on extolling it (a mentality that survived well past 1918). Nobility of birth conflated with nobility of soul, of moral worth, clearly set Jews the Jesus-killers and Jesus-deniers, Jews the landless Gypsies and usurers, apart forever. If you were noble in any sense, or aspired to be noble in any sense, you despised Jews. This must have placed incredible strain on both the intellectual and daily life of people. At least, dozens of Jewish writers keep coming back to it--for instance Ernst Weiss (like Schnitzler a medical doctor), Joseph Roth, Leo Perutz... All have written novels* about the downfall(ing) of Austro-Hungary through the characters of Austro-Hungarian officers undergoing catastrophes. (I would add to them Miroslav Krleza, who although not Jewish, and educated in military schools himself, as a member of the "lesser" Slav population of the empire acutely felt his "outsider-ness" and directly tackled the absurdity of the system.)

But Schnitzler was the first.

*Die Flucht ohne Ende, Radetzkymarsch, Boëtius von Orlamünde, Wohin rollst du, Äpfelchen...

Schnitzler is (or was, or ought to be) known well enough even in the Anglo world that the historian Peter Gay titled one of his books Schnitzler's Century. He is the first writer of the sunset of Austro-Hungary; stylistically innovative (the inner monologue in this novella predates Anglo modernism), anticipating all the great themes of the 20th century--neuroses sexual and historical, antisemitic savagery, modern anguishes of every kind.

Gustl's story is about the death of the Austro-Hungarian empire, sclerotically incapable of transformation into anything but dust. An officer but not a high-born aristocrat, Gustl is the victim of the caste system that trained him to ape the style of the long-dead aristocracy, in military dressage to love affairs to how one responds to insults. He is a relic of a strange kind--a counterfeit relic, just like Austro-Hungary had become a counterfeit empire. The middle class, the petty bourgeois, the city, the parliament, the businessmen, the financiers, had long burst the confines of the medieval hierarchies, had emptied them of real meaning. You think you're a prince because you were taught to imitate princes, then a shopkeeper comes along and calls you a dumb kid--and you see yourself for the first time in your life for what you really are--what everyone else can see you are. A useless dumbbell, a dunce fed on fairy tales, a fake with a code of honour but no right to that honour.