April-June 2013 Theme Read: South East Asia

ConversazioniReading Globally

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

1wandering_star

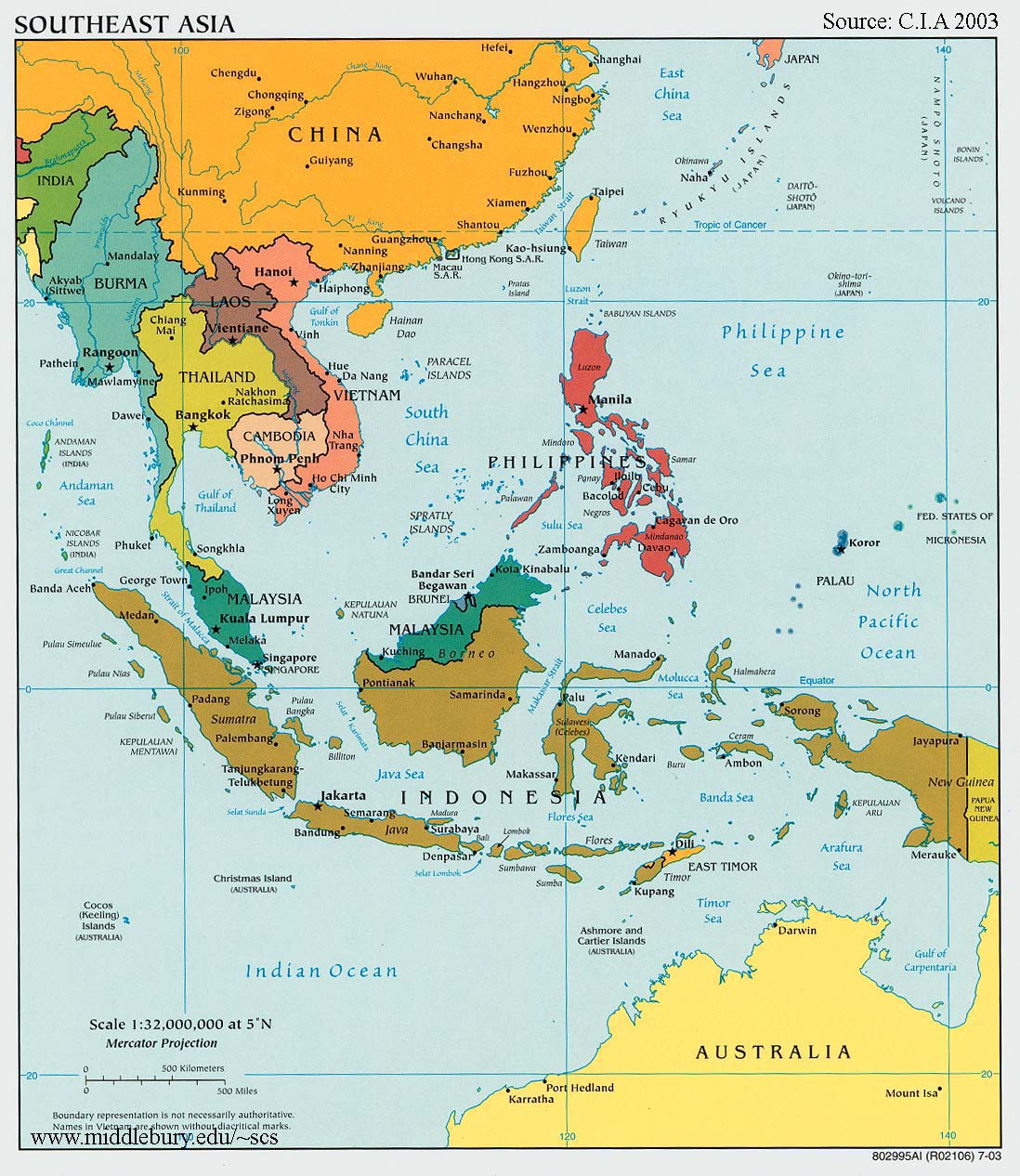

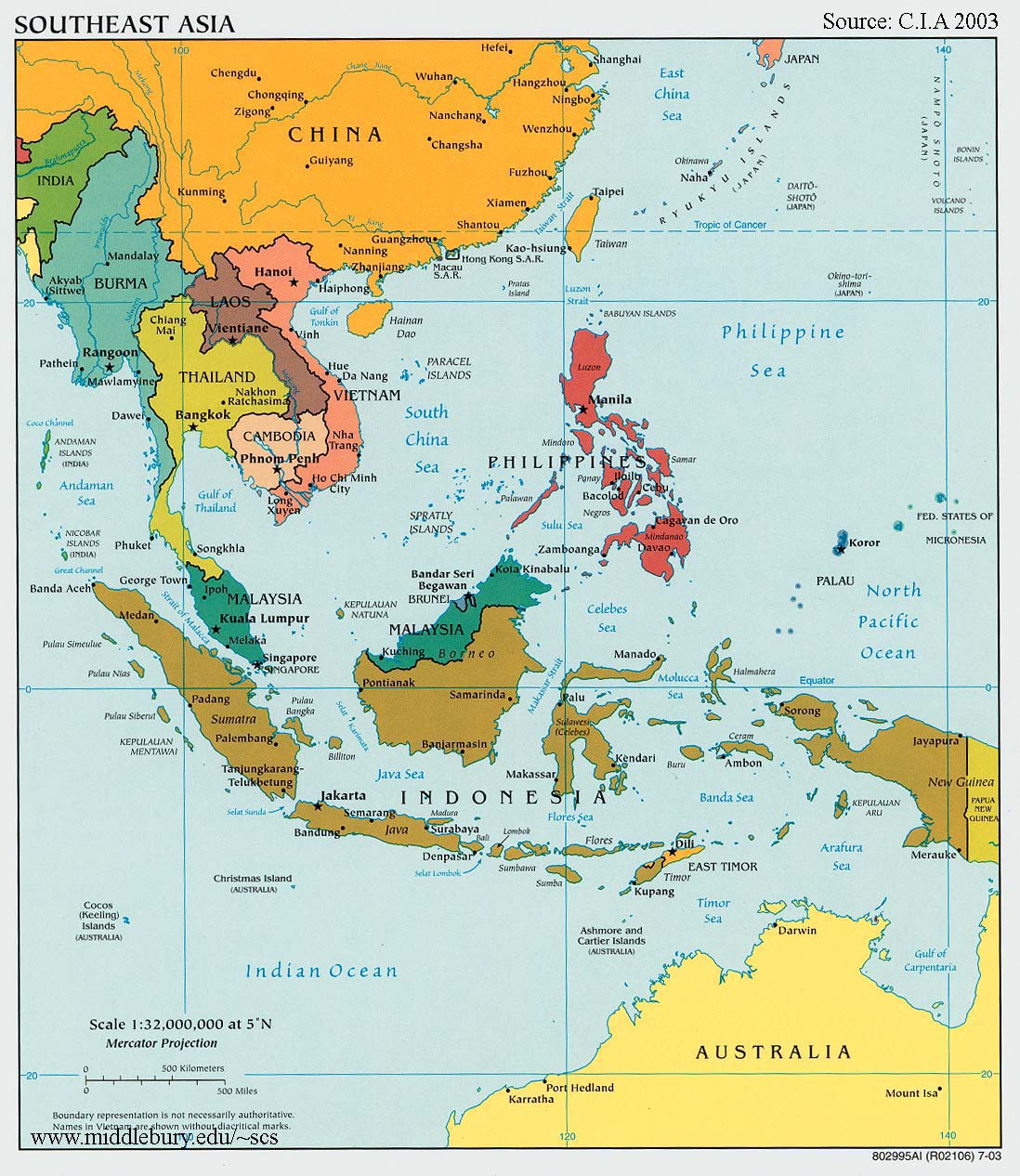

This thread is for books from and about Brunei, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Timor Leste, Thailand, and Vietnam.

Most of these countries are covered on this thread, but the Philippines is here.

Most of these countries are covered on this thread, but the Philippines is here.

2wandering_star

South East Asia is a place which has experienced several great classical kingdoms (most obviously the Khmers, who built Angkor Wat, but there were a number of others across continental South East Asia, and trading empires in maritime South East Asia) and where three world religions (Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam) have met and mixed. It now has some huge and fast-growing countries - Indonesia is the fourth most populous country in the world, and Philippines, Vietnam and Thailand are also in the top twenty.

Preparing for this theme I have been very struck by how little translated fiction is available from this part of the world. I suppose lack of translation capacity is one reason, along with relatively low levels of understanding in the West of these countries and their history. After all, even for somewhere like India, the vast majority of what's available is written in English, rather than translated.

What there is in English can broadly be divided into the following categories:

- traditional epics and myth, often based on the Ramayana, which was indigenised slightly differently in each of Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Indonesia

- anti-colonial and immediately post-colonial literature which was influential in developing a sense of national identity, such as Jose Rizal's Noli Me Tangere or Pramoedya Ananta Toer's Buru Quartet

- recent fiction, often written in English by English-speaking writers from the region (Tan Twan Eng) or by first- or second-generation migrants now living in English speaking countries

However, there is some translated work out there, including from specialist small presses - and the existence of ebooks has made these more accessible and cheaper than they would previously have been. For example, the Lontar Press' Modern Library Of Indonesia books are all available on Amazon.

In the list below I have focused mainly on books by authors from these countries, some of which are partly set elsewhere. I've also included some 'classic' fiction by outsiders, mostly dating from the colonial era, and some key non-fiction introductions to the countries. If I really can't find much by writers from that country, I've mentioned a couple by foreigners.

I'm looking forward to hearing what others have found.

Preparing for this theme I have been very struck by how little translated fiction is available from this part of the world. I suppose lack of translation capacity is one reason, along with relatively low levels of understanding in the West of these countries and their history. After all, even for somewhere like India, the vast majority of what's available is written in English, rather than translated.

What there is in English can broadly be divided into the following categories:

- traditional epics and myth, often based on the Ramayana, which was indigenised slightly differently in each of Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Indonesia

- anti-colonial and immediately post-colonial literature which was influential in developing a sense of national identity, such as Jose Rizal's Noli Me Tangere or Pramoedya Ananta Toer's Buru Quartet

- recent fiction, often written in English by English-speaking writers from the region (Tan Twan Eng) or by first- or second-generation migrants now living in English speaking countries

However, there is some translated work out there, including from specialist small presses - and the existence of ebooks has made these more accessible and cheaper than they would previously have been. For example, the Lontar Press' Modern Library Of Indonesia books are all available on Amazon.

In the list below I have focused mainly on books by authors from these countries, some of which are partly set elsewhere. I've also included some 'classic' fiction by outsiders, mostly dating from the colonial era, and some key non-fiction introductions to the countries. If I really can't find much by writers from that country, I've mentioned a couple by foreigners.

I'm looking forward to hearing what others have found.

3wandering_star

Brunei - I'm afraid I've drawn a complete blank on anything from Brunei so far...

Burma (Myanmar)

Colonial classic - Burmese Days by George Orwell, a novel inspired by Orwell's time working as a colonial civil servant in Burma (then part of British India)

Fiction -

Smile As They Bow by Nu Nu Yi

The Glass Palace by Amitav Ghosh (Indian) a family saga covering the broad sweep from the British invasion of Mandalay in 1885 until the present day

Non-fiction - several memoirs by political activists and/or about the political repression in Burma - eg From the Land of Green Ghosts: A Burmese Odyssey by Pascal Khoo Thwe , a student activist.

History - The River of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History of Burma by Thant Myint-U - a history focused on the last 60 years, from the grandson of former UN Secretary General U-Thant.

Cambodia

Fiction - haven't found anything yet

Non-fiction - several memoirs of the genocide including:

Broken Glass Floats

Stay Alive, My Son

First They Killed My Father

The Gate by Francois Bizot - a memoir of the time in 1971 when Francois Bizot an enthnologist living and working in Cambodia was imprisoned for suspicion of spying for the CIA. During his three months in prison he got to know his captor Comrade Duch, previously a school teacher, who would go on to become the chief interrogator for the Khmer Rouge.

The Lost Executioner by Nic Dunlop - a biography of the same Comrade Duch, head of the Khmer Rouge's secret police and responsible for the death of over 20,000 people. After the collapse of the regime Duch disappeared until photographer Dunlop tracked him down.

General history - Phnom Penh: A Cultural & Literary History by Milton Osborne

The Tragedy of Cambodian History by David P. Chandler (covering the time from the end of WWII until the Vietnamese invasion in 1979, particularly focusing on the civil war and the rule of Pol Pot.

Indonesia

Fiction -

Pramoedya Ananta Toer (1925–2006) - his works span the colonial period, Indonesia's struggle for independence, its occupation by Japan during the Second World War, as well as the post-colonial authoritarian regimes of Sukarno and Suharto, and are infused with personal and national history. His most famous work, The Buru Quartet, which starts with This Earth of Mankind, was written in prison. Not permitted access to writing materials, he recited the story orally to other prisoners before it was written down and smuggled out. Exile is a collection of conversations with him on politics, postcolonialism and Indonesian cultural identity.

Mochtar Lubis (1922-2004) - a journalist whose novel Twilight In Jakarta was the first Indonesian novel to be translated into English.

Modern fiction -

Of Bees And Mist - Erick Setiawan (born in Jakarta, Indonesia, to Chinese parents, moved to the US in 1991).

Saman by Ayu Utami (born 1968 in West Java)

Telegram by Putu Wijaya

The Rainbow Troops by Andrea Hirata

Jazz, Perfume and the Incident by Seno Gumira Ajidarma - an Indonesian journalist writing about East Timor

Colonial-era writing -

Max Havelaar: Or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company by Multatuli - a shocking novel in its day, written by a Dutch colonialist in protest against the way that the Dutch administration exploited indigenous farmers.

An Outcast of the Islands by Joseph Conrad - a Westerner flees from a scandal in Singapore and ends up in a native Indonesian village.

The Hidden Force (1900) by Louis Couperus - set at the height of Dutch colonial rule in the East Indies, this novel portrays the clash between Western rationalism and indigenous mysticism.

Faded Portraits by E. Breton De Nijs - a fictionalised memoir of colonial life in the Dutch East Indies.

Laos

Fiction - Mother's Beloved: Stories from Laos - Bnounyavong Outhine

Non-fiction - A History of Laos by Martin Stuart-Fox

Malaysia

Fiction -

The Gift Of Rain and The Garden Of Evening Mists - Tan Twan Eng

The Harmony Silk Factory and Map Of The Invisible World - Tash Aw

Evening Is the Whole Day by Preeta Samarasan

Green is the Colour by Lloyd Fernando (apparently these are the only two Malaysian novels which look at the 1969 race riots)

No Harvest But A Thorn - Shahnon Ahmad

Little Hut Of Leaping Fishes - Chiew-Siah Tei

Kampung Boy, a memoir - Lat

The Malayan Trilogy by Anthony Burgess (British, lived for some time in Malaya) - three novels set in post-war Malaysia which chart the demise of the British Empire.

Burma (Myanmar)

Colonial classic - Burmese Days by George Orwell, a novel inspired by Orwell's time working as a colonial civil servant in Burma (then part of British India)

Fiction -

Smile As They Bow by Nu Nu Yi

The Glass Palace by Amitav Ghosh (Indian) a family saga covering the broad sweep from the British invasion of Mandalay in 1885 until the present day

Non-fiction - several memoirs by political activists and/or about the political repression in Burma - eg From the Land of Green Ghosts: A Burmese Odyssey by Pascal Khoo Thwe , a student activist.

History - The River of Lost Footsteps: A Personal History of Burma by Thant Myint-U - a history focused on the last 60 years, from the grandson of former UN Secretary General U-Thant.

Cambodia

Fiction - haven't found anything yet

Non-fiction - several memoirs of the genocide including:

Broken Glass Floats

Stay Alive, My Son

First They Killed My Father

The Gate by Francois Bizot - a memoir of the time in 1971 when Francois Bizot an enthnologist living and working in Cambodia was imprisoned for suspicion of spying for the CIA. During his three months in prison he got to know his captor Comrade Duch, previously a school teacher, who would go on to become the chief interrogator for the Khmer Rouge.

The Lost Executioner by Nic Dunlop - a biography of the same Comrade Duch, head of the Khmer Rouge's secret police and responsible for the death of over 20,000 people. After the collapse of the regime Duch disappeared until photographer Dunlop tracked him down.

General history - Phnom Penh: A Cultural & Literary History by Milton Osborne

The Tragedy of Cambodian History by David P. Chandler (covering the time from the end of WWII until the Vietnamese invasion in 1979, particularly focusing on the civil war and the rule of Pol Pot.

Indonesia

Fiction -

Pramoedya Ananta Toer (1925–2006) - his works span the colonial period, Indonesia's struggle for independence, its occupation by Japan during the Second World War, as well as the post-colonial authoritarian regimes of Sukarno and Suharto, and are infused with personal and national history. His most famous work, The Buru Quartet, which starts with This Earth of Mankind, was written in prison. Not permitted access to writing materials, he recited the story orally to other prisoners before it was written down and smuggled out. Exile is a collection of conversations with him on politics, postcolonialism and Indonesian cultural identity.

Mochtar Lubis (1922-2004) - a journalist whose novel Twilight In Jakarta was the first Indonesian novel to be translated into English.

Modern fiction -

Of Bees And Mist - Erick Setiawan (born in Jakarta, Indonesia, to Chinese parents, moved to the US in 1991).

Saman by Ayu Utami (born 1968 in West Java)

Telegram by Putu Wijaya

The Rainbow Troops by Andrea Hirata

Jazz, Perfume and the Incident by Seno Gumira Ajidarma - an Indonesian journalist writing about East Timor

Colonial-era writing -

Max Havelaar: Or the Coffee Auctions of the Dutch Trading Company by Multatuli - a shocking novel in its day, written by a Dutch colonialist in protest against the way that the Dutch administration exploited indigenous farmers.

An Outcast of the Islands by Joseph Conrad - a Westerner flees from a scandal in Singapore and ends up in a native Indonesian village.

The Hidden Force (1900) by Louis Couperus - set at the height of Dutch colonial rule in the East Indies, this novel portrays the clash between Western rationalism and indigenous mysticism.

Faded Portraits by E. Breton De Nijs - a fictionalised memoir of colonial life in the Dutch East Indies.

Laos

Fiction - Mother's Beloved: Stories from Laos - Bnounyavong Outhine

Non-fiction - A History of Laos by Martin Stuart-Fox

Malaysia

Fiction -

The Gift Of Rain and The Garden Of Evening Mists - Tan Twan Eng

The Harmony Silk Factory and Map Of The Invisible World - Tash Aw

Evening Is the Whole Day by Preeta Samarasan

Green is the Colour by Lloyd Fernando (apparently these are the only two Malaysian novels which look at the 1969 race riots)

No Harvest But A Thorn - Shahnon Ahmad

Little Hut Of Leaping Fishes - Chiew-Siah Tei

Kampung Boy, a memoir - Lat

The Malayan Trilogy by Anthony Burgess (British, lived for some time in Malaya) - three novels set in post-war Malaysia which chart the demise of the British Empire.

4wandering_star

Philippines

Noli Me Tangere - José Rizal - an influential anti-colonialist classic

The Rosales Saga by F. Sionil José, a historical epic starting in the late 19th century - and other books by the same author

Ilustrado by Miguel Syjuco

Banana Heart Summer, Fish-Hair Woman and The Solemn Lantern Maker by Merlinda Bobis

Dogeaters (and several other books) by Jessica Hagedorn

Soledad's Sister by Jose Y. Dalisay

Great Philippine Jungle Energy Cafe (and several other books) by Alfred A Yuson

Singapore

The Bondmaid and several others by Catherine Lim

Shirley Lim

Lions In Winter, The Proper Care Of Foxes and Biophilia by Wena Poon

Mammon Inc. and Foreign Bodies by Hwee Hwee Tan

The Thorn of Lion City by Lucy Lum

Colonial life - The Singapore Grip by J.G. Farrell

Timor Leste

Nothing by Timorese authors, but three books by foreigners:

No-Name Bird by Josef Gert Vondra

The Canal House by Mark Lee, an American reporter

The Redundancy Of Courage by Hong Kong/Brit Timothy Mo

Thailand

Sightseeing by Rattawut Lapcharoensap - short stories set in modern-day Thailand.

Four Reigns, a historical novel of life in the Royal Palace, from traditional times through the to the second half of the twentieth century, by Kukrit Pramoj, who was Prime Minister of Thailand in the mid-1970s.

Other authors who appear to have books translated into English:

Prabhassorn Sevikul

Chart Korbjitti

Jane Vejjajiva

Pira Sudham

History -

A History of Thailand by Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit

Bangkok: A Cultural and Literary History by Maryvelma O'Neil

Vietnam

Fiction -

Paradise Of The Blind and several others by Dương Thu Hương

The Sorrow of War by Bao Ninh

The Dragon Prince: Stories & Legends from Vietnam by Thich Nhat Hanh

(I think only these three were written in Vietnamese - the ones below were written in English - please correct me if I am wrong)

Daughters Of The River Huong by Uyen Nicole Duong (and two others in the same series)

Grass Roof, Tin Roof by Dao Strom

Ru by Kim Thúy (born 1968 in Saigon, now living in Canada, writing in French)

Monkey Bridge by Lan Cao

The Gangster We Are All Looking For by Lê Thị Diễm Thúy

The Book Of Salt and Bitter In The Mouth by Monique Truong

Region-wide reading

The Inspector Singh series by Shamini Flint, a Singapore writer whose detective novels are set all over South East Asia

Madeleine Thien is a Canadian of Malaysian origin, and has written books set in Malaysia (Certainty) and Cambodia (Dogs At The Perimeter).

Minfong Ho was born in Burma and raised in Thailand, and her books are set in various parts of South East Asia.

Far Eastern Tales and More Far Eastern Tales - colonial-era short stories by Somerset Maugham.

Noli Me Tangere - José Rizal - an influential anti-colonialist classic

The Rosales Saga by F. Sionil José, a historical epic starting in the late 19th century - and other books by the same author

Ilustrado by Miguel Syjuco

Banana Heart Summer, Fish-Hair Woman and The Solemn Lantern Maker by Merlinda Bobis

Dogeaters (and several other books) by Jessica Hagedorn

Soledad's Sister by Jose Y. Dalisay

Great Philippine Jungle Energy Cafe (and several other books) by Alfred A Yuson

Singapore

The Bondmaid and several others by Catherine Lim

Shirley Lim

Lions In Winter, The Proper Care Of Foxes and Biophilia by Wena Poon

Mammon Inc. and Foreign Bodies by Hwee Hwee Tan

The Thorn of Lion City by Lucy Lum

Colonial life - The Singapore Grip by J.G. Farrell

Timor Leste

Nothing by Timorese authors, but three books by foreigners:

No-Name Bird by Josef Gert Vondra

The Canal House by Mark Lee, an American reporter

The Redundancy Of Courage by Hong Kong/Brit Timothy Mo

Thailand

Sightseeing by Rattawut Lapcharoensap - short stories set in modern-day Thailand.

Four Reigns, a historical novel of life in the Royal Palace, from traditional times through the to the second half of the twentieth century, by Kukrit Pramoj, who was Prime Minister of Thailand in the mid-1970s.

Other authors who appear to have books translated into English:

Prabhassorn Sevikul

Chart Korbjitti

Jane Vejjajiva

Pira Sudham

History -

A History of Thailand by Chris Baker and Pasuk Phongpaichit

Bangkok: A Cultural and Literary History by Maryvelma O'Neil

Vietnam

Fiction -

Paradise Of The Blind and several others by Dương Thu Hương

The Sorrow of War by Bao Ninh

The Dragon Prince: Stories & Legends from Vietnam by Thich Nhat Hanh

(I think only these three were written in Vietnamese - the ones below were written in English - please correct me if I am wrong)

Daughters Of The River Huong by Uyen Nicole Duong (and two others in the same series)

Grass Roof, Tin Roof by Dao Strom

Ru by Kim Thúy (born 1968 in Saigon, now living in Canada, writing in French)

Monkey Bridge by Lan Cao

The Gangster We Are All Looking For by Lê Thị Diễm Thúy

The Book Of Salt and Bitter In The Mouth by Monique Truong

Region-wide reading

The Inspector Singh series by Shamini Flint, a Singapore writer whose detective novels are set all over South East Asia

Madeleine Thien is a Canadian of Malaysian origin, and has written books set in Malaysia (Certainty) and Cambodia (Dogs At The Perimeter).

Minfong Ho was born in Burma and raised in Thailand, and her books are set in various parts of South East Asia.

Far Eastern Tales and More Far Eastern Tales - colonial-era short stories by Somerset Maugham.

5wandering_star

Further resources for South East Asian reading

A book blog by a Brit living in Malaysia for the last 26 years, with coverage of SEA literature

A couple of academic syllabi for SEA literature courses

An LT group Indonesiana (dormant)

The Singapore Lit Prize LT page

I'll add more as I find them.

A book blog by a Brit living in Malaysia for the last 26 years, with coverage of SEA literature

A couple of academic syllabi for SEA literature courses

An LT group Indonesiana (dormant)

The Singapore Lit Prize LT page

I'll add more as I find them.

6wandering_star

My planned reads:

Fiction:

Max Havelaar (Indonesia)

The Scent Of The Gods by Fiona Cheong (Singapore)

Saman (Indonesia)

Banana Heart Summer (Philippines)

An Outcast Of The Islands (Indonesia)

The Garden Of Evening Mists (Malaysia)

Non-fiction:

America's Boy (about Marcos) and Playing With Water (memoir) by James Hamilton-Paterson

Subversion As Foreign Policy: The Secret Eisenhower and Dulles Debacle in Indonesia by Audrey R. Kahin and George McT. Kahin

A House In Bali by Colin McPhee

In The Time Of Madness by Richard Lloyd Parry (journalism, Indonesia)

These are based on what I have on my shelves at the moment. You may be able to guess which ones are left over from a course I did on South East Asian Government And Politics in (urk) 1998. It's a good thing to be getting round to them 15 years later....

Fiction:

Max Havelaar (Indonesia)

The Scent Of The Gods by Fiona Cheong (Singapore)

Saman (Indonesia)

Banana Heart Summer (Philippines)

An Outcast Of The Islands (Indonesia)

The Garden Of Evening Mists (Malaysia)

Non-fiction:

America's Boy (about Marcos) and Playing With Water (memoir) by James Hamilton-Paterson

Subversion As Foreign Policy: The Secret Eisenhower and Dulles Debacle in Indonesia by Audrey R. Kahin and George McT. Kahin

A House In Bali by Colin McPhee

In The Time Of Madness by Richard Lloyd Parry (journalism, Indonesia)

These are based on what I have on my shelves at the moment. You may be able to guess which ones are left over from a course I did on South East Asian Government And Politics in (urk) 1998. It's a good thing to be getting round to them 15 years later....

8rebeccanyc

Thanks for all this great research, wandering_star, and for getting us started on an interesting quarterly read. I'll post the link on the group page.

9kidzdoc

Well done, Margaret! I plan to read these books from my TBR collection for this theme:

Fiction:

Evening Is the Whole Day by Preeta Samarasan (Malaysia)

The Gangster We Are All Looking For by Lê Thị Diễm Thúy (Vietnam)

The Harmony Silk Factory by Tash Aw (Malaysia)

Noli Me Tangere by José Rizal (Phillipines)

The Redundancy of Courage by Timothy Mo (Timor-Leste)

The Singapore Grip by J.G. Farrell (Singapore)

Non-fiction:

A House in Bali by Colin McPhee (Indonesia)

I'll probably also read Burmese Days and The Glass Palace.

Recommended books:

The Garden of Evening Mists by Tan Twan Eng

The Gift of Rain by Tan Twan Eng

Map of the Invisible World by Tash Aw

Fiction:

Evening Is the Whole Day by Preeta Samarasan (Malaysia)

The Gangster We Are All Looking For by Lê Thị Diễm Thúy (Vietnam)

The Harmony Silk Factory by Tash Aw (Malaysia)

Noli Me Tangere by José Rizal (Phillipines)

The Redundancy of Courage by Timothy Mo (Timor-Leste)

The Singapore Grip by J.G. Farrell (Singapore)

Non-fiction:

A House in Bali by Colin McPhee (Indonesia)

I'll probably also read Burmese Days and The Glass Palace.

Recommended books:

The Garden of Evening Mists by Tan Twan Eng

The Gift of Rain by Tan Twan Eng

Map of the Invisible World by Tash Aw

10Rise

Great suggestions. In addition to the ones from the Philippines, I recommend the following. I’ve read and own some of these; the rest are from my wish list.

America Is in the Heart - Carlos Bulosan

Awaiting Trespass - Linda Ty-Casper

Baby Jesus Pawn Shop - Lucia Orth

The Bamboo Dancers - N. V. M. Gonzalez

Banyaga: A Song of War - Charlson Ong

Below the Crying Mountain - Criselda Yabes

But for the Lovers - Wilfrido D. Nolledo

The Disinherited - Han Ong

Eating Fire and Drinking Water - Arlene J. Chai

Empire of Memory - Eric Gamalinda

Farah - Edilberto K. Tiempo

Ghosts of Manila - James Hamilton Paterson

The Gold in Makiling - Macario Pineda, trans. Soledad S. Reyes

Gun Dealers' Daughter - Gina Apostol

The Hand of the Enemy - Kerima Polotan

His Native Coast - Edith L. Tiempo

Leche - R. Zamora Linmark

Letters to Montgomery Clift - Noel Alumit

Longitude: A Novel - Carlos Cortes

Margosatubig: The Story of Salagunting - Ramon L. Muzones, trans. Ma. Cecilia Locsin Nava

Recuerdo (Philippine Writers Series) - Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo

Salamanca - Dean Francis Alfar

Samboangan: The Cult of War - Antonio R. Enriquez

Smaller and Smaller Circles - F. H. Batacan

Viajero - F. Sionil Jose

Twice Blessed - Ninotchka Rosca

Villa Magdalena - Bienvenido N. Santos

Without Seeing the Dawn - Stevan Javellana

The Woman Who Had Two Navels - Nick Joaquin

Women of Tammuz - Azucena Grajo Uranza

America Is in the Heart - Carlos Bulosan

Awaiting Trespass - Linda Ty-Casper

Baby Jesus Pawn Shop - Lucia Orth

The Bamboo Dancers - N. V. M. Gonzalez

Banyaga: A Song of War - Charlson Ong

Below the Crying Mountain - Criselda Yabes

But for the Lovers - Wilfrido D. Nolledo

The Disinherited - Han Ong

Eating Fire and Drinking Water - Arlene J. Chai

Empire of Memory - Eric Gamalinda

Farah - Edilberto K. Tiempo

Ghosts of Manila - James Hamilton Paterson

The Gold in Makiling - Macario Pineda, trans. Soledad S. Reyes

Gun Dealers' Daughter - Gina Apostol

The Hand of the Enemy - Kerima Polotan

His Native Coast - Edith L. Tiempo

Leche - R. Zamora Linmark

Letters to Montgomery Clift - Noel Alumit

Longitude: A Novel - Carlos Cortes

Margosatubig: The Story of Salagunting - Ramon L. Muzones, trans. Ma. Cecilia Locsin Nava

Recuerdo (Philippine Writers Series) - Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo

Salamanca - Dean Francis Alfar

Samboangan: The Cult of War - Antonio R. Enriquez

Smaller and Smaller Circles - F. H. Batacan

Viajero - F. Sionil Jose

Twice Blessed - Ninotchka Rosca

Villa Magdalena - Bienvenido N. Santos

Without Seeing the Dawn - Stevan Javellana

The Woman Who Had Two Navels - Nick Joaquin

Women of Tammuz - Azucena Grajo Uranza

11whymaggiemay

Margaret, I appreciate the wonderful introduction to South East Asia. I'd forgotten that this was coming up this year and thus have done some jumping ahead, but still have lots to keep my busy.

There is at least one fiction book about Cambodia In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner, the daughter of a prince of the ancient Imperial family, who wrote a novel loosely based on her family's experiences at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. I've read and recommend it.

If one wants a British view of 1800s Colonial Burma, there is The Piano Tuner by Daniel Mason. Certainly not a translated work by a native, but beautifully written and gives a good taste of that time in history from the British perspective.

On Vietnam I've read and recommend The Monkey Bridge (touchstone wrong) by Lan Cao and The North China Lover by Marguerite Duras in fiction and Catfish and Mandala by Andrew X. Pham in nonfiction (travel). About the Vietnam War I've also read The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien and a nonfiction book about nurses in the Vietnam War, the name of which escapes me. Both were excellent.

On my shelves I have and hope to read:

The Gift of Rain by Tan Twan Eng (The Garden of the Evening Mists was wonderful)

The Gate by Francois Bizot

I'm sure I'll get some great suggestions from the above.

There is at least one fiction book about Cambodia In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner, the daughter of a prince of the ancient Imperial family, who wrote a novel loosely based on her family's experiences at the hands of the Khmer Rouge. I've read and recommend it.

If one wants a British view of 1800s Colonial Burma, there is The Piano Tuner by Daniel Mason. Certainly not a translated work by a native, but beautifully written and gives a good taste of that time in history from the British perspective.

On Vietnam I've read and recommend The Monkey Bridge (touchstone wrong) by Lan Cao and The North China Lover by Marguerite Duras in fiction and Catfish and Mandala by Andrew X. Pham in nonfiction (travel). About the Vietnam War I've also read The Things They Carried by Tim O'Brien and a nonfiction book about nurses in the Vietnam War, the name of which escapes me. Both were excellent.

On my shelves I have and hope to read:

The Gift of Rain by Tan Twan Eng (The Garden of the Evening Mists was wonderful)

The Gate by Francois Bizot

I'm sure I'll get some great suggestions from the above.

12whymaggiemay

#10, as a native of the Philippines, where would you suggest I begin my reading? There is so much to choose from and 5-6 suggestions would be helpful, especially since some may be difficult to get. Thanks.

13Rise

Hi, Maggie. I think the good places to start are the ones listed by Margaret in #5, especially Noli Me Tangere, Soledad's Sister, and Tree, F. Sionil José (in Don Vicente). In addition: America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan, Salamanca by Dean Francis Alfar, and Recuerdo, Cristina Pantoja Hidalgo.

14judylou

Another excellent story about Vietnam is The Headmaster's Wager by Vincent Lam.

15SassyLassy

Wonderful list w_s! I'm really looking forward to this quarter's discussions.

For Cambodia, I would also suggest two older books by William Shawcross, both very detailed: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia and The Quality of Mercy: Cambodia, Holocaust and Modern Conscience. Then there is François Ponchaud's memoir Cambodia: Year Zero.

I only bought two books for this read (so far), as one will take a long time: The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79 by Ben Kiernan. The other one you mentioned already, Paradise of the Blind. The Gate is on my TBR pile. I suspect there will be more.

Ru has now been translated into English.

Glad to see The Malayan Trilogy there. I read it a long time ago and thought it was great.

Just occurred to me too, for Vietnam, although not a Vietnamese writer, but a great book, Graham Greene's The Quiet American, which was one of Michael Caine's best roles.

A WWII memoir of Malaysia, Eric Lomax, The Railway Man

>11 whymaggiemay: maggie, was the book on nurses Nurses in Vietnam: The Forgotten Veterans? I found this in a used book store in September but haven't read it yet. There is also 365 Days by an army surgeon.

For Cambodia, I would also suggest two older books by William Shawcross, both very detailed: Sideshow: Kissinger, Nixon and the Destruction of Cambodia and The Quality of Mercy: Cambodia, Holocaust and Modern Conscience. Then there is François Ponchaud's memoir Cambodia: Year Zero.

I only bought two books for this read (so far), as one will take a long time: The Pol Pot Regime: Race, Power and Genocide in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, 1975-79 by Ben Kiernan. The other one you mentioned already, Paradise of the Blind. The Gate is on my TBR pile. I suspect there will be more.

Ru has now been translated into English.

Glad to see The Malayan Trilogy there. I read it a long time ago and thought it was great.

Just occurred to me too, for Vietnam, although not a Vietnamese writer, but a great book, Graham Greene's The Quiet American, which was one of Michael Caine's best roles.

A WWII memoir of Malaysia, Eric Lomax, The Railway Man

>11 whymaggiemay: maggie, was the book on nurses Nurses in Vietnam: The Forgotten Veterans? I found this in a used book store in September but haven't read it yet. There is also 365 Days by an army surgeon.

16whymaggiemay

#13, Rise, thank you for the list. I'll definitely see what I can find written in English.

#15, SassyLassy, I looked up the nurses book. It was A Piece of My Heart: The Stories of 26 American Women Who Served in Vietnam by Keith Walker. It was interesting because some of them were Red Cross workers, diplomats, or others in Vietnam, not serving in the military. Most of them had suffered PTS as a result of their experiences.

#15, SassyLassy, I looked up the nurses book. It was A Piece of My Heart: The Stories of 26 American Women Who Served in Vietnam by Keith Walker. It was interesting because some of them were Red Cross workers, diplomats, or others in Vietnam, not serving in the military. Most of them had suffered PTS as a result of their experiences.

17dianahaler

I enjoyed The Blue Afternoon by William Boyd. Parts of this novel are set in Manila in 1902, during the US occupation of the Philippines. It will not be the same as reading a translated work, but this book is vividly written and gave me some insight into that period.

18Samantha_kathy

I plan to read The Rice Mother by Rani Manicka, a Malaysian author. Although she currently lives in the England, and I believe the novel was originally written in English, it's a purely Malaysian novel.

19wandering_star

Thanks for all these, and especially the Cambodia fiction recommendation - nice to fill a gap. I recommend Evening Is the Whole Day and The Railway Man, and I think the Ben Kiernan book was one of the ones I actually read when I was doing the course!

I also have A House in Bali and will plan to get to it this quarter.

I also have A House in Bali and will plan to get to it this quarter.

20rebeccanyc

So much to choose from.

I have read one book by a contemporary Vietnamese author who immigrated to Paris, The Three Fates by Linda Le. I've read excellent books by Americans about Vietnam and the Vietnamese war and would definitely like to read some from the Vietnamese perspective, i.e., about the American war. And I'd like to explore some other parts of Southeast Asia too.

I have read one book by a contemporary Vietnamese author who immigrated to Paris, The Three Fates by Linda Le. I've read excellent books by Americans about Vietnam and the Vietnamese war and would definitely like to read some from the Vietnamese perspective, i.e., about the American war. And I'd like to explore some other parts of Southeast Asia too.

21streamsong

Thich Nhat Hanh had some very disturbing comments about American policy and participation in the Vietnam war in one of his books that I read. They were very brief, actually only a sidebar comment. But, I think I'll pursue something by him about the war. I've read several of his books on Buddhism, but none on the war. Since Martin Luther King, Jr endorsed his nomination of the Nobel Peace Prize in regard to his activity during the war, it should be interesting reading. I've also not read any of his fiction or short stories. If anyone has suggestions, I'd love to hear them. That man's output is phenomenal!

ETA: I'm thinking perhaps Fragrant Palm Leaves: Journals, 1962-1966 or The Moon Bamboo.

ETA: I'm thinking perhaps Fragrant Palm Leaves: Journals, 1962-1966 or The Moon Bamboo.

22cameling

For additional Singapore reads, I would recommend Tanamera by Noel Barber, The Red Thread : A Chinese Tale of Love and Fate in 1830s Singapore by Farnham Dawn, Battle for Singapore by Peter Thompson.

I have Lee's Lieutenants in my TBR Tower that I will be planning to read for this challenge.

For Indonesia, I'd recommend Island of Demons by Nigel Barley.

I have Lee's Lieutenants in my TBR Tower that I will be planning to read for this challenge.

For Indonesia, I'd recommend Island of Demons by Nigel Barley.

23banjo123

Nice job on the thread wandering star! I am looking forward to the reading.

Of the books mentioned, I have read Garden of the Evening Mists which is beautiful. Also, I would recommend When Broken Glass Floats which is a very well-writtne book about growing up under the Khmer Rouge. THe author, Chanrithy Him is also a Portland girl. Her family immigrated to Portland and she went to high school a few miles from my house.

My planned reads are:

The Gift of Rain

The Harmony Silk Factory by Tash Aw

The Headmaster's Wager by Vincent Lam

The Beauty of Humanity Movement by Camilla GIbb

and In the Shadow of the Banyan

Of the books mentioned, I have read Garden of the Evening Mists which is beautiful. Also, I would recommend When Broken Glass Floats which is a very well-writtne book about growing up under the Khmer Rouge. THe author, Chanrithy Him is also a Portland girl. Her family immigrated to Portland and she went to high school a few miles from my house.

My planned reads are:

The Gift of Rain

The Harmony Silk Factory by Tash Aw

The Headmaster's Wager by Vincent Lam

The Beauty of Humanity Movement by Camilla GIbb

and In the Shadow of the Banyan

24LizzySiddal

Two brilliant reads:

The Lizard's Cage - Karen Connelly (Burma)

- Review at: http://lizzysiddal.wordpress.com/2007/08/12/the-lizard-cage-karen-connelly/

The Garden of Evening Mists - Tan Twan Eng (Malaysia)

Review at:

http://lizzysiddal.wordpress.com/2012/10/12/booker-2012-the-garden-of-evening-mi...

The Lizard's Cage - Karen Connelly (Burma)

- Review at: http://lizzysiddal.wordpress.com/2007/08/12/the-lizard-cage-karen-connelly/

The Garden of Evening Mists - Tan Twan Eng (Malaysia)

Review at:

http://lizzysiddal.wordpress.com/2012/10/12/booker-2012-the-garden-of-evening-mi...

25rebeccanyc

Well, I've succumbed to Amazon and ordered the following books: Smile as they Bow by Nu Nu Yi, The Sorrow of War: A Novel of North Vietnam by Bao Ninh, and This Earth of Mankind by Pramoedya Ananta Toer.

26whymaggiemay

#24, thanks for the reminder of The Lizard's Cage, I have it on Mt. TBR and will consider it for this read.

27brenpike

Inside Out and Back Again by Thanhha Lai and Last Night I Dreamed of Peace by Dang Thuy Tram, both about Vietnam, were books I found rewarding last year.

28chrisharpe

> 21 streamsong. There used to be a video documentary somewhere on the Internet about Thich Nhat Hanh's experience of the Viet Nam war. I've just made a quick search and can't immediately find it - maybe other know where to find it?

As I remember, it was over an hour long and filmed by a US Viet Nam vet who is now a follower of TNH. Although TNH practised and advocated forgiveness, he did not pull his punches in describing the suffering he had witnessed at the hands of the US military. I found the film very moving - inspiring. It would make good background for reading about Viet Nam, or for studying TNH.

As I remember, it was over an hour long and filmed by a US Viet Nam vet who is now a follower of TNH. Although TNH practised and advocated forgiveness, he did not pull his punches in describing the suffering he had witnessed at the hands of the US military. I found the film very moving - inspiring. It would make good background for reading about Viet Nam, or for studying TNH.

29OshoOsho

If you're looking for books from the region, especially Cambodia and Laos, I recommend Monument Books: http://monument-books.com/ . Their interface is often slow. If you're in Cambodia or Laos (or the Siem Reap or Phnom Penh airports), their bookstores are great fun. They have a good range of regional non-fiction. I've read and reviewed a fair amount about Cambodia, though I haven't yet dared look at whether my shelf labels from Goodreads have converted to tags here.

30rebeccanyc

Welcome to LT and to Reading Globally, OshoOsho! It's great to have someone with your reading experience here, especially for this Theme Read.

32banjo123

That's great OshoOsho. I would like to read more non-fiction about Cambodia, if you have recommendations.

33banjo123

In the Shadow of the Banyan by Vaddey Ratner

This is an autobiographical novel. Vaddey Ratner was 5 when the Khmer Rouge came to power in 1975. Her family was Cambodian royalty and used to a privileged life in a loving family. She spent the next four years in forced labor, starvation and near execution. She survived, though many family members perished, and arrived in the US in 1981.

I was somewhat frustrated with this novel, and if you are going to read one book on growing up under the Khmer Rouge, I recommend When Broken Glass Floats by Chanrithy Him. Him’s book is a memoir, rather than a novel, which I feel works better for a writer who is mainly trying to bear witness to the horrors of an oppressive regime. In a novel, one expects plot and character development; a memoir can focus only on a story of survival against great odds. Also, Him’s writing style is more direct. When I read her book, I felt I had a much greater understanding of what it’s like to be so hungry that you will eat bugs, grubs, or whatever you can find. The craziness randomness of the regime, which, in addition to killing many, many people, also destroyed its own country’s economic and agricultural infrastructure was better illustrated. Him also described life in the refugee camps, which Ratner does not.

Another frustration with Ratner’s work is that her narrator’s voice did not ring true. Raami’s voice simply seems to sophisticated and too selfless for that of a young child.

On the positive side: I think that this story is very close to Ratner’s own experiences and is quite accurate, other than my quibble with the narrator’s voice. Her experiences were really similar to Him’s. Ratner does do a good job of showing the contrast between Raami’s previous life as a princess, and her life under the Khmer Rouge.

The strongest part of this book is Ratner’s description of her father and her relationship with him. Sisowath Ayuravann does seem to have been a remarkable man. He was a poet who told his daughter many stories. Ratner has the father tell Raami “I told you stories to give you wings, Raami, so that you would never be trapped by anything—your name, your title, the limits of your body, this world’s suffering.”

This is an autobiographical novel. Vaddey Ratner was 5 when the Khmer Rouge came to power in 1975. Her family was Cambodian royalty and used to a privileged life in a loving family. She spent the next four years in forced labor, starvation and near execution. She survived, though many family members perished, and arrived in the US in 1981.

I was somewhat frustrated with this novel, and if you are going to read one book on growing up under the Khmer Rouge, I recommend When Broken Glass Floats by Chanrithy Him. Him’s book is a memoir, rather than a novel, which I feel works better for a writer who is mainly trying to bear witness to the horrors of an oppressive regime. In a novel, one expects plot and character development; a memoir can focus only on a story of survival against great odds. Also, Him’s writing style is more direct. When I read her book, I felt I had a much greater understanding of what it’s like to be so hungry that you will eat bugs, grubs, or whatever you can find. The craziness randomness of the regime, which, in addition to killing many, many people, also destroyed its own country’s economic and agricultural infrastructure was better illustrated. Him also described life in the refugee camps, which Ratner does not.

Another frustration with Ratner’s work is that her narrator’s voice did not ring true. Raami’s voice simply seems to sophisticated and too selfless for that of a young child.

On the positive side: I think that this story is very close to Ratner’s own experiences and is quite accurate, other than my quibble with the narrator’s voice. Her experiences were really similar to Him’s. Ratner does do a good job of showing the contrast between Raami’s previous life as a princess, and her life under the Khmer Rouge.

The strongest part of this book is Ratner’s description of her father and her relationship with him. Sisowath Ayuravann does seem to have been a remarkable man. He was a poet who told his daughter many stories. Ratner has the father tell Raami “I told you stories to give you wings, Raami, so that you would never be trapped by anything—your name, your title, the limits of your body, this world’s suffering.”

34rebeccanyc

Interesting review, Banjo, and also thanks for the comparison to the memoir.

35plt

I really enjoyed your review and I have added When Broken Glass Floats to my TBR pile. Wondering if you've read First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung which received similar criticisms to the ones you discuss with regard to voice.

36kidzdoc

Last night I finished an Early Reviewers copy of Five Star Billionaire by the Malaysian author Tash Aw, a superb novel about five Malaysian emigrants in modern day Shanghai. I'm not sure where I should post my review, though; the author and characters are Malaysian, and it could go here, but the story is mainly about Shanghai, with only oblique references to Malaysia, so it seems as though the recent theme on China and neighboring countries would be a better fit. Thoughts?

37streamsong

Kidzdoc-- How about both?

Sounds like a very interesting premise. Wherever you place it, I'll look forward to your review.

Sounds like a very interesting premise. Wherever you place it, I'll look forward to your review.

39kidzdoc

>37 streamsong: How about both?

I thought about that too, streamsong, as I could make an equally valid argument for posting my review in either theme. I'm working on my review now, and I'll post it later today, or tomorrow at the latest.

>38 plt: Good thought, Peg. If I decide to post my review in the China and neighboring countries thread I'll at least post a link to it here. According to the cover, Five Star Billionaire won't be available in the US until July 2nd, but it was published in the UK in late February. It's nearly 400 pages long, and I read all but the first 50 or so pages in a single sitting yesterday afternoon and evening.

I thought about that too, streamsong, as I could make an equally valid argument for posting my review in either theme. I'm working on my review now, and I'll post it later today, or tomorrow at the latest.

>38 plt: Good thought, Peg. If I decide to post my review in the China and neighboring countries thread I'll at least post a link to it here. According to the cover, Five Star Billionaire won't be available in the US until July 2nd, but it was published in the UK in late February. It's nearly 400 pages long, and I read all but the first 50 or so pages in a single sitting yesterday afternoon and evening.

41rebeccanyc

I usually go by the national origin of the author, but that's just me.

42kidzdoc

>41 rebeccanyc: That was the basis of my argument for posting my review of Five Star Billionaire here, Rebecca. However, a book like The Singapore Grip by J.G. Farrell, which I'll read for this theme, would seem to be more appropriately placed under Singapore rather than England, which would be my argument for posting my review of Aw's latest book in the China and neighboring countries thread. I'll probably post it in both places.

43kidzdoc

Five Star Billionaire by Tash Aw

Shanghai is a beautiful place, but it is also a harsh place. Life here is not really life, it is a competition.

Shanghai is the world's largest city, with a total population of over 23 million. It can arguably claim to be the city of the 21st century, similar to 19th century London and 20th century New York, as it is a booming financial, commercial and entertainment center that attracts emigrants and visitors from every continent, and it is the leading symbol of the new China and its growing influence on Asia and the rest of the world.

Tash Aw was born in Taipei to Malaysian parents, grew up in Kuala Lumpur, was educated in the UK, and lived in London before he moved to Shanghai after he was chosen to be the first M Literary Writer in Residence in 2010. In this superb novel, he portrays five Malaysian Chinese who have moved to Shanghai to seek the wealth and prestige that the city seems to offer to each of its newcomers.

Phoebe is a naïve and uneducated young woman from the Malaysian countryside, who emigrates illegally to China on the suggestion of a friend, but soon after she arrives she finds that the dream job she was promised has suddenly vanished. Justin is the eldest son of a wealthy real estate tycoon, charged with purchasing a property in Shanghai that will save his family from ruin in the face of the Asian financial crisis. Gary is a pop mega-star who performs in front of thousands of adoring fans, while battling internal demons that threaten to destroy his career. Yinghui is the daughter of a prominent family in Kuala Lumpur who transforms herself from a left wing political activist into a hard nosed and successful businesswoman. Finally, Walter is a secretive and shadowy figure who has risen up from the ashes of his father's ruin to become a prominent developer and the anonymous author of the best selling book "How to Become a Five Star Billionaire". The first four characters are all interlinked with Walter, the only person given a voice in the first person in the book, in an intricately woven web that slowly tightens around each of them.

Through these characters, Tash Aw provides a fascinating internal glimpse into modern Shanghai, a city filled with ambitious but often lonely and desperate people from all over Asia whose singular focus on material goods and wealth outweighs love and personal happiness. Anything and anyone is fair game for exploitation and deceit, and the widespread availability of counterfeit watches, purses and clothing mimics the superficiality of the city's high stakes capitalist culture. Self help books such as the one written by Walter are the bibles of the young up-and-comers, and traditional Chinese culture is viewed as outdated and stifling to young people like Phoebe.

Each one attains some degree of success, but several meet with sudden and spectacular failure, in the matter of a climber that reaches the summit of a mountain only to be blown off of it entirely by a sudden gust of wind.

Five Star Billionaire is a captivating work about Shanghai and the new China, and the lives of five talented and determined people who seek wealth and fulfillment but find loneliness and misery instead. I read nearly all of this novel in a single sitting, and I was quite sorry to see it end. I also loved Tash Aw's previous novel Map of the Invisible World, and I look forward to reading The Harmony Silk Factory later this year.

Shanghai is a beautiful place, but it is also a harsh place. Life here is not really life, it is a competition.

Shanghai is the world's largest city, with a total population of over 23 million. It can arguably claim to be the city of the 21st century, similar to 19th century London and 20th century New York, as it is a booming financial, commercial and entertainment center that attracts emigrants and visitors from every continent, and it is the leading symbol of the new China and its growing influence on Asia and the rest of the world.

Tash Aw was born in Taipei to Malaysian parents, grew up in Kuala Lumpur, was educated in the UK, and lived in London before he moved to Shanghai after he was chosen to be the first M Literary Writer in Residence in 2010. In this superb novel, he portrays five Malaysian Chinese who have moved to Shanghai to seek the wealth and prestige that the city seems to offer to each of its newcomers.

Phoebe is a naïve and uneducated young woman from the Malaysian countryside, who emigrates illegally to China on the suggestion of a friend, but soon after she arrives she finds that the dream job she was promised has suddenly vanished. Justin is the eldest son of a wealthy real estate tycoon, charged with purchasing a property in Shanghai that will save his family from ruin in the face of the Asian financial crisis. Gary is a pop mega-star who performs in front of thousands of adoring fans, while battling internal demons that threaten to destroy his career. Yinghui is the daughter of a prominent family in Kuala Lumpur who transforms herself from a left wing political activist into a hard nosed and successful businesswoman. Finally, Walter is a secretive and shadowy figure who has risen up from the ashes of his father's ruin to become a prominent developer and the anonymous author of the best selling book "How to Become a Five Star Billionaire". The first four characters are all interlinked with Walter, the only person given a voice in the first person in the book, in an intricately woven web that slowly tightens around each of them.

Through these characters, Tash Aw provides a fascinating internal glimpse into modern Shanghai, a city filled with ambitious but often lonely and desperate people from all over Asia whose singular focus on material goods and wealth outweighs love and personal happiness. Anything and anyone is fair game for exploitation and deceit, and the widespread availability of counterfeit watches, purses and clothing mimics the superficiality of the city's high stakes capitalist culture. Self help books such as the one written by Walter are the bibles of the young up-and-comers, and traditional Chinese culture is viewed as outdated and stifling to young people like Phoebe.

Each one attains some degree of success, but several meet with sudden and spectacular failure, in the matter of a climber that reaches the summit of a mountain only to be blown off of it entirely by a sudden gust of wind.

The city held its promises just out of your reach, waiting to see how far you were willing to go to get what you wanted, how long you were prepared to wait. And until you determined the parameters of your pursuit, you would be on edge, for despite the restaurants and shops and art galleries and sense of unbridled potential, you would always feel that Shanghai was accelerating a couple of steps ahead of you, no matter how hard you worked or played. The crowds, the traffic, the impenetrable dialect, the muddy rains that carried the remnants of the Gobi Desert sandstorms and stained your clothes every March: The city was teasing you, testing your limits, using you. You arrived thinking you were going to use Shanghai to get what you wanted, and it would be some time before you realized that it was using you, that it had already moved on and you were playing catch up.

Five Star Billionaire is a captivating work about Shanghai and the new China, and the lives of five talented and determined people who seek wealth and fulfillment but find loneliness and misery instead. I read nearly all of this novel in a single sitting, and I was quite sorry to see it end. I also loved Tash Aw's previous novel Map of the Invisible World, and I look forward to reading The Harmony Silk Factory later this year.

44rebeccanyc

BURMA/MYANMAR

Smile As They Bow by Nu Nu Yi

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

Well, the best thing about this novella was the picture it painted of an unfamiliar (to me) culture, specifically the festivals honoring nats (or spirits) in Taungbyon, Burma, and the natkadaws, or spirit wives, now mostly transvestites but historically women, who "embody" the spirits and make and distribute a lot of money in the process. Through the thoughts and actions of the primary character, a transvestite known as Daisy Bond, as well as those of several secondary characters, the reader sees how the natkadaws acquire and manage their followers, largely wealthy women, who shower them with gifts and money so the spirits they channel will bring them even more wealth and success; the competition for placement in the processions to the various temples over the course of the seven-day festival; the difficulties of aging; the struggles of the poor through begging and through actually being sold to wealthier people; and the way the festival has started attracting tourists from all over, as well as all those who would like to make money from them, including trinket-sellers and pickpockets.

All of this is interesting in an anthropological way, but as a story it bordered on the soap-operaish. It was also interesting to have a picture of life in Burma/Myanmar apart from the political oppression that is more familiar to those of us in the west. Nu Nu Yi is apparently a popular and prolific writer in Burma/Myanmar, but this is her only work to have been translated into English; it was short-listed for the Man Asia literary prize.

Needless to say, I have no familiarity with Burmese, and the translation, by another Burmese woman and a man who has spent a lot of time there, seemed generally OK to me. But I was struck by references to people born on certain days of the week, which apparently has some astrological or zodiacal significance, because they used our western names for the days. I looked this up on Wikipedia, and there is a correlation between the Burmese system and our system, but I found the use of western names for the days jarring and would have preferred the translators to keep the Burmese words as they did for various other spirit-related terminology.

For more information on nats and nat festivals, see this Wikipedia article. I also note on the web that there are quite a few travel agencies offering trips to the Taungbyon festival. There's no business like (religious) show business!

Smile As They Bow by Nu Nu Yi

Cross-posted from my Club Read and 75 Books threads

Well, the best thing about this novella was the picture it painted of an unfamiliar (to me) culture, specifically the festivals honoring nats (or spirits) in Taungbyon, Burma, and the natkadaws, or spirit wives, now mostly transvestites but historically women, who "embody" the spirits and make and distribute a lot of money in the process. Through the thoughts and actions of the primary character, a transvestite known as Daisy Bond, as well as those of several secondary characters, the reader sees how the natkadaws acquire and manage their followers, largely wealthy women, who shower them with gifts and money so the spirits they channel will bring them even more wealth and success; the competition for placement in the processions to the various temples over the course of the seven-day festival; the difficulties of aging; the struggles of the poor through begging and through actually being sold to wealthier people; and the way the festival has started attracting tourists from all over, as well as all those who would like to make money from them, including trinket-sellers and pickpockets.

All of this is interesting in an anthropological way, but as a story it bordered on the soap-operaish. It was also interesting to have a picture of life in Burma/Myanmar apart from the political oppression that is more familiar to those of us in the west. Nu Nu Yi is apparently a popular and prolific writer in Burma/Myanmar, but this is her only work to have been translated into English; it was short-listed for the Man Asia literary prize.

Needless to say, I have no familiarity with Burmese, and the translation, by another Burmese woman and a man who has spent a lot of time there, seemed generally OK to me. But I was struck by references to people born on certain days of the week, which apparently has some astrological or zodiacal significance, because they used our western names for the days. I looked this up on Wikipedia, and there is a correlation between the Burmese system and our system, but I found the use of western names for the days jarring and would have preferred the translators to keep the Burmese words as they did for various other spirit-related terminology.

For more information on nats and nat festivals, see this Wikipedia article. I also note on the web that there are quite a few travel agencies offering trips to the Taungbyon festival. There's no business like (religious) show business!

45StevenTX

VIETNAM

Paradise of the Blind by Duong Thu Huong

First published in Vietnamese 1988

English translation by Phan Huy Duong and Nina McPherson 1993

Paradise of the Blind tells the story of a Vietnamese woman named Hang growing up in Hanoi in the 1970s and 1980s. Her life reflects the painful conflicts between the deep-rooted traditions and family values of Vietnam's rural past and the harsh, often hypocritical policies and attitudes of its socialist present.

The novel opens with Hang, who is an "imported worker" at a textile plant somewhere in Russia, being summoned to the bedside of her ailing uncle in Moscow. Though Hang is herself quite ill, it is her duty to obey. On the long train journey she reflects back upon her childhood and youth.

Hang grew up the illegitimate and only child of her mother, Que, who works as a street vendor in Hanoi. They live a hand-to-mouth existence in a filthy slum under a leaky tar paper roof. Que lives a simple life "according to proverbs and duties." When her brother, Hang's uncle Chinh, a minor party official, demands money or food, Que obeys even if she and Hang must go hungry.

The other woman in Hang's life is the sister of the father she never knew, her Aunt Tam. Where Que is resigned and fatalistic, Tam is hopeful and defiant. She fights the system that has robbed her family of its former wealth and position, slowly battling her way back to prosperity for the sake of Hang, her only living relative. "It was through her," says Hang, "that I knew the tenderness of this world, and through her too that I was linked to the chains of my past, to the pain of existence." Hang is caught between her filial obligations to her mother, her emotional ties to Aunt Tam, and the demands of society represented by Uncle Chinh.

The novel was first published and sold in Vietnam, then banned. This suggests that the author's depiction of Vietnamese life is right on the borderline of what was considered tolerable at that time. She doesn't criticize the communist system itself, but shows the failures of its policies and the hypocrisy and corruption they engendered. Poverty, malnutrition and a lack of sanitation are everywhere evident, even (and this is most surprising) in the homes of party officials.

But there are bright moments in which we get a look at the traditions of Vietnamese folk life, especially the food. The preparation of everything from simple fare to elaborate feasts is described in considerable detail. Some of the dishes are mouth-watering and tempt the reader to try following the cooking instructions. Others are more daunting, such as Hang's favorite delicacy, a pudding made of congealed duck's blood topped with liver, garlic and peanuts. There is even a glossary of Vietnamese words that is devoted mostly to culinary terms.

Paradise of the Blind is a beautifully written account of life in modern Vietnam, as well as a moving story of the struggle we all face to balance the demands of family, self, and society.

Paradise of the Blind by Duong Thu Huong

First published in Vietnamese 1988

English translation by Phan Huy Duong and Nina McPherson 1993

Paradise of the Blind tells the story of a Vietnamese woman named Hang growing up in Hanoi in the 1970s and 1980s. Her life reflects the painful conflicts between the deep-rooted traditions and family values of Vietnam's rural past and the harsh, often hypocritical policies and attitudes of its socialist present.

The novel opens with Hang, who is an "imported worker" at a textile plant somewhere in Russia, being summoned to the bedside of her ailing uncle in Moscow. Though Hang is herself quite ill, it is her duty to obey. On the long train journey she reflects back upon her childhood and youth.

Hang grew up the illegitimate and only child of her mother, Que, who works as a street vendor in Hanoi. They live a hand-to-mouth existence in a filthy slum under a leaky tar paper roof. Que lives a simple life "according to proverbs and duties." When her brother, Hang's uncle Chinh, a minor party official, demands money or food, Que obeys even if she and Hang must go hungry.

The other woman in Hang's life is the sister of the father she never knew, her Aunt Tam. Where Que is resigned and fatalistic, Tam is hopeful and defiant. She fights the system that has robbed her family of its former wealth and position, slowly battling her way back to prosperity for the sake of Hang, her only living relative. "It was through her," says Hang, "that I knew the tenderness of this world, and through her too that I was linked to the chains of my past, to the pain of existence." Hang is caught between her filial obligations to her mother, her emotional ties to Aunt Tam, and the demands of society represented by Uncle Chinh.

The novel was first published and sold in Vietnam, then banned. This suggests that the author's depiction of Vietnamese life is right on the borderline of what was considered tolerable at that time. She doesn't criticize the communist system itself, but shows the failures of its policies and the hypocrisy and corruption they engendered. Poverty, malnutrition and a lack of sanitation are everywhere evident, even (and this is most surprising) in the homes of party officials.

But there are bright moments in which we get a look at the traditions of Vietnamese folk life, especially the food. The preparation of everything from simple fare to elaborate feasts is described in considerable detail. Some of the dishes are mouth-watering and tempt the reader to try following the cooking instructions. Others are more daunting, such as Hang's favorite delicacy, a pudding made of congealed duck's blood topped with liver, garlic and peanuts. There is even a glossary of Vietnamese words that is devoted mostly to culinary terms.

Paradise of the Blind is a beautifully written account of life in modern Vietnam, as well as a moving story of the struggle we all face to balance the demands of family, self, and society.

46GlebtheDancer

I hope nobody minds, but I have cross posted a review from my own thread that I read about a year ago. I wouldn't normally do this, but it is the same book that Rebecca reviewed above (message 44) so I thought I would add my thoughts. I think its fair to say that my review is more positive than Rebecca's, though they are broadly similar. I think both of us were interested (and surprised?) by the cultural setting, but neither of us were very impressed with the narrative (described as 'soap-opera ish by her and 'incidental' by me).

Smile as They Bow by Nu Nu Yi

Smile as They bow was short-listed for the Man Asia Literary prize in 2007. The MAL is a newish discovery on my part and, based on the first couple of books I have read that have been nominated, well worth checking out, both in terms of books from countries that are a little off the usual literary map, but also as a source of good literature.

Smile as They Bow is a short novel based around the Taungbyon festival in central Myanmar. The festival is a primarily gay celebration in which transvestites called natkadaw channel spirits called nats to respond to prayers and requests from the public. The story follows a prominent ageing natkadaw called 'Daisy Bond' as he attempts to maintain his eminence among the natkadaw in the face of competition for business and competition for his younger lover. Daisy is a fascinating character, publicly waspish and fiery, privately vulnerable, he abuses his friends and the general public but desperately needs their approval and attention. Over the course of a couple of days of the festival, Daisy is forced to work harder than ever before to cling to his relationships and his position of power at Taungbyon.

I really enjoyed Smile as They Bow. For such a small book, Nu Nu Yi manages to develop Daisy's character wonderfully well. The festival is also enchanting, with all the kitsch and flamboyance of a pride carnival, but with a strong spiritual aspect thrown in. The narrative itself (i.e. Daisy's attempts to cling to his power and his lover) is almost incidental to the descriptions of the setting and characters, but that is in no way detrimental to the book as a whole. Setting, subject matter and author nationality all made this a unique read for me, and it is not one I will forget in a hurry.

It is definitely recommended for anyone looking for a Myanmar book for their reading challenges, but also a general thumbs up as a fascinating short novel.

Smile as They Bow by Nu Nu Yi

Smile as They bow was short-listed for the Man Asia Literary prize in 2007. The MAL is a newish discovery on my part and, based on the first couple of books I have read that have been nominated, well worth checking out, both in terms of books from countries that are a little off the usual literary map, but also as a source of good literature.

Smile as They Bow is a short novel based around the Taungbyon festival in central Myanmar. The festival is a primarily gay celebration in which transvestites called natkadaw channel spirits called nats to respond to prayers and requests from the public. The story follows a prominent ageing natkadaw called 'Daisy Bond' as he attempts to maintain his eminence among the natkadaw in the face of competition for business and competition for his younger lover. Daisy is a fascinating character, publicly waspish and fiery, privately vulnerable, he abuses his friends and the general public but desperately needs their approval and attention. Over the course of a couple of days of the festival, Daisy is forced to work harder than ever before to cling to his relationships and his position of power at Taungbyon.

I really enjoyed Smile as They Bow. For such a small book, Nu Nu Yi manages to develop Daisy's character wonderfully well. The festival is also enchanting, with all the kitsch and flamboyance of a pride carnival, but with a strong spiritual aspect thrown in. The narrative itself (i.e. Daisy's attempts to cling to his power and his lover) is almost incidental to the descriptions of the setting and characters, but that is in no way detrimental to the book as a whole. Setting, subject matter and author nationality all made this a unique read for me, and it is not one I will forget in a hurry.

It is definitely recommended for anyone looking for a Myanmar book for their reading challenges, but also a general thumbs up as a fascinating short novel.

47rebeccanyc

Andy, I had forgotten that you had read this and I enjoyed reading your review (again?). I agree with everything you wrote; I don't think I felt negatively about the book, because it did present such an unfamiliar and surprising cultural event so well even though I felt the plot lacking. And I do agree that Nu Nu Yi developed Daisy's character well. I have to say, though, I found the festival, with its emphasis on money and catering to ever-growing numbers of tourists, more appalling than "enchanting." It made me wonder how much of that is modern and how much goes back to the centuries-old origins of the festival, when women, not transvestites, were the natkadaws.

48Rise

I read this book in the first quarter.

PHILIPPINES

Salamanca by Dean Francis Alfar (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2006)

A fecund, oversexed imagination is on display in this first novel by Dean Francis Alfar, the main proponent of speculative fiction in the Philippines. The sorcery of the title refers to the fuel that powers an imaginary Spanish galleon to soar through the skies. The galleon is a fixture in certain fantastical short stories written by Gaudencio Rivera, the bisexual male lead of the novel. His fount of creativity is derived from his love affairs, betrayals, and promiscuity. Lovemaking fuels Gaudencio's haphazard literary activity.

Sometime in the 1950s, Gaudencio runs away from Manila to Palawan Island to escape a love affair gone wrong. There he encounters Jacinta Cordova, a young woman of peerless beauty. "Her beauty was of such purity and perfection that the walls of the house she lived in had turned transparent long ago, to allow both sunlight and moonlight to illuminate her incandescence." This is a love story.

The magical absurdity of that passage is consistent with the novel's use of lust and love as materials for fictional creation. It is a creative act that expands fictional boundaries, for we are in the territory of magical realism. It is easy to fall prey to the trappings and overused routines of magic. Alfar's beautiful sentences, however, are the building blocks of a luminous structure that is this very novel.

Salamanca manages to convey significant aspects of postwar Philippine history while telling an exuberant tale of love, identity, and exile. The way Alfar intertwined the landmarks and history of the Palawan Island setting into the novel's larger story is particularly awesome (at least to me, who is living in Palawan for almost decade now).

The novel deploys magic as more than an instrument of speculation. Magic is here a transgressive force. The early scene of a powerful storm for instance—wherein the characters, together with their freely flowing hormones, are carried aloft by an accelerating whirlwind—is an outrageous, comic set piece. Unlike the barren magic of popular novelists like Haruki Murakami, the magic in Salamanca is disabused of its false stupefaction.

The seemingly whimsical telling of the plot creates spontaneous magic. Gaudencio exploits his experiences, his loves, and his many betrayals of them—like his betrayal of Jacinta that resulted to their short-lived wedding—as materials for his writing career. Similarly, Alfar churns up new plot elements and characters with the spontaneous resolve of an aesthete. Part of his strength lies in the efficiency of his quick character sketches. Characters are added incrementally, and despite their brief appearances and the spare details about them, the readers feel invested in their stories.

There's a lot to unpack in this short novel which in its own way offers a synthesis of post-war Philippine history, not a magical slice of that history but the whole cake. At the start of the novel, Gaudencio is in the United States, homesick and planning to return to the Philippines to impregnate his estranged wife Jacinta.

Manilaville is a settlement for Filipinos in Louisiana, later destroyed by a powerful hurricane. Gaudencio mirrors the experience of immigrant Filipino writers, those who continue to long for their country even as they seek to establish their literary careers abroad. The name has a correlate with Vietville which also figures in the novel. Vietville is a settlement community of Vietnamese, the first generation of which were Vietnamese refugees who fled their country during the Vietnam War. They arrived by boat to Palawan after a long sea journey. The plight of exiled citizens and writers, what defines their rootedness in a certain home country, is one of the novel's dramatic strands.

This novel is also notable for its bending not only of genre but of gender. "Men, Women and Other Fictions" is the title of the second of three chapters of the novel, indicating how gender is here (almost) ignored as a deterministic criteria in choosing the sexual orientation of characters. The bisexual Gaudencio fills a gender gap in the characterization of male lovers in Philippine literary novels, at least novels of "epic and sprawling" ambition like Salamanca, novels which consciously integrate historical details in their text.

Most significantly, Alfar makes a metaphoric case for sexual appetite as the "life force" of literary imagination.

The imagined leap from the promiscuity of procreation to the promiscuity of creativity is one way of looking at art as perpetual giving birth to artworks, the progeny of the imagination. Sexual reproduction as the mode of literary production. The prolific outputs of Gaudencio are direct products of his sexual proclivity. "His muse was the instant of passion", that instant when he "experienced his body's familiar transubstantiation of carnal lust to sublime vocabularies, and he would mentally partition texts as they were composed in his mind". Alfar seems to be hinting that, in the continuing process of national imagining and becoming, the liberal attitudes toward sexuality is the liberating force that makes us aware of the mystery of love and existence.

Self-awareness is a modernist quality of Salamanca. It is a highly aware novel, aware of its opportunistic "exploitation" of human experience as fictional material, of magical elements as a creative force, of the politics of literary creation, of the national literary tradition it seeks to be an essential part of, and of the debilitating histories of colonialism and dictatorship. The witty self-references and historical asides, along with transgressive magic and emotional subtlety, make for a novel of verbal and sensual riches.

One character in the novel describes salamanca as the thing that makes one see what is being described. This is the power of imagery to reveal images from words alone. This is also the power of fiction to portray ideas that reflect the sheen of reality. Through some hitherto unheard of black magic sourced from some enchanted cave, Alfar shows that the novel is a magical thing too—salamanca itself.

PHILIPPINES

Salamanca by Dean Francis Alfar (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2006)

A fecund, oversexed imagination is on display in this first novel by Dean Francis Alfar, the main proponent of speculative fiction in the Philippines. The sorcery of the title refers to the fuel that powers an imaginary Spanish galleon to soar through the skies. The galleon is a fixture in certain fantastical short stories written by Gaudencio Rivera, the bisexual male lead of the novel. His fount of creativity is derived from his love affairs, betrayals, and promiscuity. Lovemaking fuels Gaudencio's haphazard literary activity.

Sometime in the 1950s, Gaudencio runs away from Manila to Palawan Island to escape a love affair gone wrong. There he encounters Jacinta Cordova, a young woman of peerless beauty. "Her beauty was of such purity and perfection that the walls of the house she lived in had turned transparent long ago, to allow both sunlight and moonlight to illuminate her incandescence." This is a love story.