The Sonnets by William Shakespeare - cynara tutoring rosalita

Questa conversazione è stata continuata da The Sonnets by William Shakespeare - cynara tutoring rosalita (Part the Second).

Conversazioni75 Books Challenge for 2012

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

Questa conversazione è attualmente segnalata come "addormentata"—l'ultimo messaggio è più vecchio di 90 giorni. Puoi rianimarla postando una risposta.

1rosalita

Welcome to my tutored read of Shakespeare's Sonnets. Cynara has agreed to be my guide throughout. Here's the structure we've agreed on:

I'd be happy to have others join in the discussion. I would only request that you allow Cynara and me to post our initial question-and-answer posts for each sonnet before chiming in. After that, jump right in!

Edited because it's never too late to eliminate embarrassing typos!

- I'll start off with a first post (hey, you're reading it now!) laying out the ground rules. I'll follow that up with a separate post explaining why I wanted to read this book with a tutor, and stating what I hope to get out of it.

- Cynara has some introductory material that she'll post that will give some tips on reading poetry in general and sonnets in particular. (Cynara, I hope I've got that right. At any rate, she will post something that is sure to teach me something I don't already know!)

- Once the preliminaries are out of the way, we'll start with the sonnets. Because they are short (and in the public domain) I will post the full text of each sonnet, along with some of my initial reactions or questions. Cynara will respond, and we'll go back and forth until we feel we've exhausted that particular sonnet. At that point, I'll post the next one, and we'll start all over again.

- There are 154 (!) sonnets. I had no idea, frankly. Cynara and I have agreed that if any of them don't spark any good reaction on my part, we'll probably just skip them. I'll still post the text, I think, just for the sake of completeness, and in case that particular sonnet is the favorite of a lurker who would like to passionately defend it. :)

I'd be happy to have others join in the discussion. I would only request that you allow Cynara and me to post our initial question-and-answer posts for each sonnet before chiming in. After that, jump right in!

Edited because it's never too late to eliminate embarrassing typos!

2rosalita

OK, so why Shakespeare's sonnets?

It should come as no surprise (since we are all here at a website called LibraryThing, in a group called the 75-Book Challenge) that I love to read. I've been reading since I was 4, and I can read just about anything. Fiction, nonfiction, mysteries, science fiction, history, biography, whatever.

But when it comes to poetry, I really feel out of my comfort zone. I never took a poetry appreciation course, and all I ever remember learning is that you shouldn't read them with a sing-song rythym. But is that true for all poetry, or just the stuff that doesn't rhyme, or what? And what the heck is iambic pentameter, anyway?

What I'm saying is that poems just intimidate me. So, of course, I avoid them. But I want to like them! I really, really do! That's where Cynara comes in, and this tutored read.

It should come as no surprise (since we are all here at a website called LibraryThing, in a group called the 75-Book Challenge) that I love to read. I've been reading since I was 4, and I can read just about anything. Fiction, nonfiction, mysteries, science fiction, history, biography, whatever.

But when it comes to poetry, I really feel out of my comfort zone. I never took a poetry appreciation course, and all I ever remember learning is that you shouldn't read them with a sing-song rythym. But is that true for all poetry, or just the stuff that doesn't rhyme, or what? And what the heck is iambic pentameter, anyway?

What I'm saying is that poems just intimidate me. So, of course, I avoid them. But I want to like them! I really, really do! That's where Cynara comes in, and this tutored read.

3Cynara

Hi, Rosa! I am so excited to start this.

(For anyone who might be wondering what the heck qualifies me to tutor these poems.)

I'm something of an English teacher (qualified, supply teaching & tutoring, waiting for baby boomers to retire), and I've loved Shakespeare since I was a little slip of a thing being taken to plays by my theatre prof dad. I fell in love with poetry through W. H. Auden's In Memory of W. B. Yeats, and I've taught poetry analysis before. That said, I never did grad work in Shakespeare or poetry in general, so I'm not a super-expert in Shakespeare's sonnets.

//poems just intimidate me//

I can see why. Often people are given the impression that poetry is cryptic, hard to read. The truth is that often it's like any other kind of reading. There's cussed old Ezra Pound, who wants to be difficult, but most poets want their work to be enjoyable and rewarding to anyone who picks up a book.

It's true that it's cool to know about the tricks poets use and the in-jokes of the poetic tradition, but some of that you get just by reading, and most of it is quick to learn.

Now, Shakespeare (or as I tend to call him, Will) can be a bit challenging due to the (from our point of view) archaic and (from his point of view) consciously poetic language he's using. People didn't talk like this every day, any more than we talk like Emily Dickinson (or Franz Wright). Poetry is emotional and it's economical with language. Each sentence is doing the work of ten sentences of prose.

Anyway, I didn't mean to start ranting about Poetry In General.

I'll be back in a minute with some specific info on the sonnets.

(For anyone who might be wondering what the heck qualifies me to tutor these poems.)

I'm something of an English teacher (qualified, supply teaching & tutoring, waiting for baby boomers to retire), and I've loved Shakespeare since I was a little slip of a thing being taken to plays by my theatre prof dad. I fell in love with poetry through W. H. Auden's In Memory of W. B. Yeats, and I've taught poetry analysis before. That said, I never did grad work in Shakespeare or poetry in general, so I'm not a super-expert in Shakespeare's sonnets.

//poems just intimidate me//

I can see why. Often people are given the impression that poetry is cryptic, hard to read. The truth is that often it's like any other kind of reading. There's cussed old Ezra Pound, who wants to be difficult, but most poets want their work to be enjoyable and rewarding to anyone who picks up a book.

It's true that it's cool to know about the tricks poets use and the in-jokes of the poetic tradition, but some of that you get just by reading, and most of it is quick to learn.

Now, Shakespeare (or as I tend to call him, Will) can be a bit challenging due to the (from our point of view) archaic and (from his point of view) consciously poetic language he's using. People didn't talk like this every day, any more than we talk like Emily Dickinson (or Franz Wright). Poetry is emotional and it's economical with language. Each sentence is doing the work of ten sentences of prose.

Anyway, I didn't mean to start ranting about Poetry In General.

I'll be back in a minute with some specific info on the sonnets.

4Cynara

//you shouldn't read them with a sing-song rythym//

Eeeeeyah. Often when kids read poetry they think they have to do that "poetry voice", and teachers stamp that down as soon as possible. I mean, who wants to hear "How DO i LOVE thee LET me COUNT the WAYS?"

If you imagine yourself looking dead into the audience's eyes and asking "How do I love thee? Let me count the ways" quietly and sincerely, like it's a real question and a real statement, it's usually so much better. The rhythm is subtle, but you don't have to force it.

Modern poetry flirts with meter, sometimes abandoning it all together, sometimes using it for a few lines to make a point, and sometimes using traditional forms like the sonnet. On the other hand, rhythm (or meter) is one of the great joys of poetry, and I would be the last woman to say you shouldn't get into the trochaic* stomp of:

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea,

When the blue wave rolls nightly on the Galilee.

Frankly, I think Lord Byron would be very disappointed if you tried to read it too naturalistically. Get in there! "Like the LEAVES of the FORest when SUMmer is GREEN..."! The poem will tell you how it wants to sound.

*a trochee is a foot which is a unit of meter and is like an iamb... wait, I'm getting all cart-before-horse here, give me a minute.

Iambic Pentameter

da DAH da DAH da DAH da DAH da DAH

When I do count the clock that tells the time...

Each "da DAH" is called an iamb. Five of them in a row is called iambic pentameter (like a pentacle or a pentagon - five, right?).

Iambic pentameter is the basic ten-syllable-per-line rhythm of the sonnet. It's messed up all the time, sometimes to draw attention to a word or phrase, sometimes because it needs to be disrupted to keep things interesting, and sometimes because the word the poet needed to use wouldn't fit properly. Whenever Will messes up his rhythm, keep your eye on him - he's probably doing it to make a point, because that man could write even rhythm like nobody's business.

There's a wonderful website called Shakespeare Online, and that link will take you to a quick discussion of meter, if you want to know more. They're the best reference I've found for these poems, and I have no doubt I will be copying from them liberally.

More notes on feet, for anyone who cares:

There are different names for different rhythmic units (aka feet): iamb, anapest, trochee, dactyll, etc. If you have two feet in a line instead of five, you call it dimeter; if six, hexameter. For example, iambic trimeter is "da DAH da DAH da DAH" in each line.

For comparison, a trochee, which is the foot Byron was using up above is "da da DAH", and he's using it in a tetrameter line, i.e. four of them - so, trochaic tetrameter is the meter of that poem.

Eeeeeyah. Often when kids read poetry they think they have to do that "poetry voice", and teachers stamp that down as soon as possible. I mean, who wants to hear "How DO i LOVE thee LET me COUNT the WAYS?"

If you imagine yourself looking dead into the audience's eyes and asking "How do I love thee? Let me count the ways" quietly and sincerely, like it's a real question and a real statement, it's usually so much better. The rhythm is subtle, but you don't have to force it.

Modern poetry flirts with meter, sometimes abandoning it all together, sometimes using it for a few lines to make a point, and sometimes using traditional forms like the sonnet. On the other hand, rhythm (or meter) is one of the great joys of poetry, and I would be the last woman to say you shouldn't get into the trochaic* stomp of:

The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold,

And his cohorts were gleaming in purple and gold;

And the sheen of their spears was like stars on the sea,

When the blue wave rolls nightly on the Galilee.

Frankly, I think Lord Byron would be very disappointed if you tried to read it too naturalistically. Get in there! "Like the LEAVES of the FORest when SUMmer is GREEN..."! The poem will tell you how it wants to sound.

*a trochee is a foot which is a unit of meter and is like an iamb... wait, I'm getting all cart-before-horse here, give me a minute.

Iambic Pentameter

da DAH da DAH da DAH da DAH da DAH

When I do count the clock that tells the time...

Each "da DAH" is called an iamb. Five of them in a row is called iambic pentameter (like a pentacle or a pentagon - five, right?).

Iambic pentameter is the basic ten-syllable-per-line rhythm of the sonnet. It's messed up all the time, sometimes to draw attention to a word or phrase, sometimes because it needs to be disrupted to keep things interesting, and sometimes because the word the poet needed to use wouldn't fit properly. Whenever Will messes up his rhythm, keep your eye on him - he's probably doing it to make a point, because that man could write even rhythm like nobody's business.

There's a wonderful website called Shakespeare Online, and that link will take you to a quick discussion of meter, if you want to know more. They're the best reference I've found for these poems, and I have no doubt I will be copying from them liberally.

More notes on feet, for anyone who cares:

There are different names for different rhythmic units (aka feet): iamb, anapest, trochee, dactyll, etc. If you have two feet in a line instead of five, you call it dimeter; if six, hexameter. For example, iambic trimeter is "da DAH da DAH da DAH" in each line.

For comparison, a trochee, which is the foot Byron was using up above is "da da DAH", and he's using it in a tetrameter line, i.e. four of them - so, trochaic tetrameter is the meter of that poem.

5Cynara

I swear, this is my last post for now. This is the bit I wrote yesterday, as an intro to the sonnets.

Here are some things you might want to know about Shakespeare's sonnets:

1. Like many writers from his time (and earlier) he probably initially wrote them for himself and his friends. Can you imagine saying "here's a collection of one hundred and fifty sonnets about my romantically obsessive relationship with George and my sexually obsessive relationship with Laura. Yeah, take a look."

There's some evidence that he passed them around for years before they came out in a book for the reading public, and that was pretty normal. They came out when he was about 45 years old, and was nearing the end of his writing career, but we're pretty sure he had written a bunch of them at least ten years earlier, in the middle of his career.

2. The sonnets have three major characters: the narrator, the young man, and the dark (-haired) lady. There's also a "rival poet" who gets a few references. Naturally, one or two hundred years of literary scholars have worn themselves to shreds trying to figure out who these people were. Maybe they were real people, maybe not. They're written in the first person; is the narrator really Shakespeare, or a character he's making up because it makes good poems? See what you think when you've read a bunch of them, Rosalita, because your opinion is as good as anyone's.

3. We don't know if the order of the sonnets matters or not; maybe it was Shakespeare's, maybe it was the publisher's. Some people say that they make no sense in the accepted order; other people will swear up and down that this order is the only one that makes any sense. Again, see what you think.

4. There's a big controversy about the dedication of the first edition, which came out during Will's life. You can ignore it if you find it boring. Who the heck is being talking about, and why is the author saying such bizarre and obsequious things? Does it give us a clue to the identity of the Young Man? Who wrote the dedication? Etc. Wikipedia does a good summary here, and I'd be happy to lay it out here if you find it intriguing.

5. There's some raunchy stuff in here. In fact, Will's sonnets are different from the traditional ones; more wrenching, more dirty, more personal. He plays with gender, and he likes a bit of parody. That said, he's also writing some fairly conventional sonnets, and we can see he's aware of the poetic tradition.

6. Like everything to do with Shakespeare scholarship, some people have trouble keeping their marbles*. There are a plethora of theories out there that give an over-arching significance to the whole set of poems, under the surface story of love and obsession. I think many of them have an element of truth. There's a gay theory, a religion theory, a satire theory, etc. etc.

In the end, it's about giving the sonnets some time and seeing if you love them. Everything else is just bookkeeping and trivia games.

*I love Oscar Wilde's mild question re. whether the commentators on Hamlet were mad or only pretending to be so.

Here are some things you might want to know about Shakespeare's sonnets:

1. Like many writers from his time (and earlier) he probably initially wrote them for himself and his friends. Can you imagine saying "here's a collection of one hundred and fifty sonnets about my romantically obsessive relationship with George and my sexually obsessive relationship with Laura. Yeah, take a look."

There's some evidence that he passed them around for years before they came out in a book for the reading public, and that was pretty normal. They came out when he was about 45 years old, and was nearing the end of his writing career, but we're pretty sure he had written a bunch of them at least ten years earlier, in the middle of his career.

2. The sonnets have three major characters: the narrator, the young man, and the dark (-haired) lady. There's also a "rival poet" who gets a few references. Naturally, one or two hundred years of literary scholars have worn themselves to shreds trying to figure out who these people were. Maybe they were real people, maybe not. They're written in the first person; is the narrator really Shakespeare, or a character he's making up because it makes good poems? See what you think when you've read a bunch of them, Rosalita, because your opinion is as good as anyone's.

3. We don't know if the order of the sonnets matters or not; maybe it was Shakespeare's, maybe it was the publisher's. Some people say that they make no sense in the accepted order; other people will swear up and down that this order is the only one that makes any sense. Again, see what you think.

4. There's a big controversy about the dedication of the first edition, which came out during Will's life. You can ignore it if you find it boring. Who the heck is being talking about, and why is the author saying such bizarre and obsequious things? Does it give us a clue to the identity of the Young Man? Who wrote the dedication? Etc. Wikipedia does a good summary here, and I'd be happy to lay it out here if you find it intriguing.

5. There's some raunchy stuff in here. In fact, Will's sonnets are different from the traditional ones; more wrenching, more dirty, more personal. He plays with gender, and he likes a bit of parody. That said, he's also writing some fairly conventional sonnets, and we can see he's aware of the poetic tradition.

6. Like everything to do with Shakespeare scholarship, some people have trouble keeping their marbles*. There are a plethora of theories out there that give an over-arching significance to the whole set of poems, under the surface story of love and obsession. I think many of them have an element of truth. There's a gay theory, a religion theory, a satire theory, etc. etc.

In the end, it's about giving the sonnets some time and seeing if you love them. Everything else is just bookkeeping and trivia games.

*I love Oscar Wilde's mild question re. whether the commentators on Hamlet were mad or only pretending to be so.

6rosalita

Cynara, this is just a spectacular introduction! You have managed to make me even more excited about this tutored read, and I thought I was pretty enthusiastic already. I can't wait to post the first sonnet (tomorrow evening; bedtime for me now) and get the party started.

7Cynara

I'm looking forward to it! Sorry about the torrent of prose up above: I'll try for more Kafka and less Charles Dickens in the future.

8rosalita

Seriously, it was just the right amount for someone like me who's a total poetry newbie. I read every word!

9rosalita

I should perhaps mention that the edition I am using was published in 1998 by Bulfinch Press. It is a very bare-bones edition: no critical notes or analysis, just a few pen-and-ink sketches. The book opens with a dedication that I think is part of the original manuscript (is that right, Cynara?):

This is a perfect sonnet to start with, because it illustrates the problem I have reading poetry. I started it thinking I knew what was going on, then I realized I had no idea what he was saying, then at the end I thought I maybe knew what he was saying, but probably not. :) Maybe it would help if I broke it down:

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease

His tender heir might bear his memory:

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies —

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

And only herald to the gaudy spring

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl mak'st waste in niggarding.

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

Over to you, Cynara!

To the only begetter ofI've read just enough to know that there is all kinds of speculation about who the mysterious W.H. is, and why the sonnets were dedicated to him, etc. I'll be honest that I'm not so interested in all that unless you think it would add to my enjoyment/understanding of the sonnets. So with that, I'll jump right to Sonnet 1:

these insuing sonnets

Mr W.H. all happinesse

and that eternity

promised

by

our ever-living poet

wisheth

the well-wishing

adventurer in

setting

forth

— T.T.

From fairest creatures we desire increase,The drawing is of a long-stemmed rose, with lots of leafy bits still attached (obviously, I am not a gardener!)

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease

His tender heir might bear his memory:

But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies —

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl mak'st waste in niggarding.

Pity the world, or else this glutton be —

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

This is a perfect sonnet to start with, because it illustrates the problem I have reading poetry. I started it thinking I knew what was going on, then I realized I had no idea what he was saying, then at the end I thought I maybe knew what he was saying, but probably not. :) Maybe it would help if I broke it down:

From fairest creatures we desire increase,

That thereby beauty's rose might never die,

But as the riper should by time decease

His tender heir might bear his memory:

We want beautiful things and people to reproduce to provide us with more beautiful things to admire?But thou, contracted to thine own bright eyes,

Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel,

Making a famine where abundance lies —

Thyself thy foe, to thy sweet self too cruel.

'Feed'st thy light's flame with self-substantial fuel' sounds like he's saying the person he's addressing is in love with himself, maybe? I like the way "to thy sweet self too cruel" hearkens back to "to thine own self be true". That whole line sounds like another way of saying the person is their own worst enemy; because they are so self-centered?Thou that art now the world's fresh ornament

And only herald to the gaudy spring

Within thine own bud buriest thy content,

And tender churl mak'st waste in niggarding.

Your beauty is reknowned now, but you carry the seeds of your own destruction inside you? But how? 'Churl' and 'niggarding' both seem to refer to being stingy or miserly with … something.Pity the world, or else this glutton be —

To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee.

I got nothin'.

Over to you, Cynara!

10Cynara

unless you think it would add to my enjoyment/understanding of the sonnets

Not in the slightest. It's from the first edition, and may have been written by Shakespeare or his publisher.

So, No. 1! It's a curiously gentle start to the whole lot, and not really a major crowd favourite. It's probably not the one I would have led with.

The first seventeen sonnets are often called the "procreation sonnets" by modern scholars. Some of the other ones suggest that they're addressed to a young man - aka the Young Man character I mentioned earlier. They're all cajoling him into marrying and producing heirs, and here our Narrator is telling him that it would be a crime for beauty like his to be lost to the general gene pool.

So, you got the gist and you understood the purpose of many of the metaphors:

//in love with himself,//

// the person is their own worst enemy; because they are so self-centered?//

Exactly.

Here's my modern English adaptation (sorry, Will):

We want beautiful creatures to have children,

So that through children, their beauty will never die.

So, when age takes one's beauty and one's life

The beautiful person's heir will keep his memory alive:

But you, engaged to your own beautiful bright eyes

Feed your bright beauty on your own self

Starving yourself although you have all the natural advantages -

You're your own foe, too cruel to yourself.

You - who are now the world's greatest beauty

And the announcer of the green spring

Find all your pleasure within yourself

And, you sweet idiot, waste all that pleasure by keeping it all to yourself.

Pity the world (and have children), or else be like this glutton:

Someone who eats both his portion and the world's.

Apparently there's a distinct implication of... solitary pleasure in "Within thine own bud buriest thy content". An apt rebuke for a young man who refuses to marry and have children.

Definitely keep doing what you're doing - figure out generally what he's saying. Having an edition with notes can be very helpful here, but if something is particularly stumping you, try The Shakespeare Glossery over at shakespeare-online.

Also, as you go, you'll get a feel for the language and it will become easier!

Here's something to keep in mind - what kind of comparisons and metaphors is he using here? They'll echo through the rest of the sonnets, too. Is there different imagery* associated with a good beautiful person, who marries, and with a bad beautiful person, who spends all their time looking in a mirror?

*Imagery!

Metaphor: Rosalita is a rose

Simile: Rosalita is like a rose, or Rosalita is as beautiful as a rose.

Sometimes adjectives and description have a particular flavour, too: Rosalita is verdant but thorny, silken-petaled, fast-growing, fades in a strong sun, but fills the garden with wonder under the moonlight. I didn't actually *call* you a flower, but I may as well have.

Not in the slightest. It's from the first edition, and may have been written by Shakespeare or his publisher.

So, No. 1! It's a curiously gentle start to the whole lot, and not really a major crowd favourite. It's probably not the one I would have led with.

The first seventeen sonnets are often called the "procreation sonnets" by modern scholars. Some of the other ones suggest that they're addressed to a young man - aka the Young Man character I mentioned earlier. They're all cajoling him into marrying and producing heirs, and here our Narrator is telling him that it would be a crime for beauty like his to be lost to the general gene pool.

So, you got the gist and you understood the purpose of many of the metaphors:

//in love with himself,//

// the person is their own worst enemy; because they are so self-centered?//

Exactly.

Here's my modern English adaptation (sorry, Will):

We want beautiful creatures to have children,

So that through children, their beauty will never die.

So, when age takes one's beauty and one's life

The beautiful person's heir will keep his memory alive:

But you, engaged to your own beautiful bright eyes

Feed your bright beauty on your own self

Starving yourself although you have all the natural advantages -

You're your own foe, too cruel to yourself.

You - who are now the world's greatest beauty

And the announcer of the green spring

Find all your pleasure within yourself

And, you sweet idiot, waste all that pleasure by keeping it all to yourself.

Pity the world (and have children), or else be like this glutton:

Someone who eats both his portion and the world's.

Apparently there's a distinct implication of... solitary pleasure in "Within thine own bud buriest thy content". An apt rebuke for a young man who refuses to marry and have children.

Definitely keep doing what you're doing - figure out generally what he's saying. Having an edition with notes can be very helpful here, but if something is particularly stumping you, try The Shakespeare Glossery over at shakespeare-online.

Also, as you go, you'll get a feel for the language and it will become easier!

Here's something to keep in mind - what kind of comparisons and metaphors is he using here? They'll echo through the rest of the sonnets, too. Is there different imagery* associated with a good beautiful person, who marries, and with a bad beautiful person, who spends all their time looking in a mirror?

*Imagery!

Metaphor: Rosalita is a rose

Simile: Rosalita is like a rose, or Rosalita is as beautiful as a rose.

Sometimes adjectives and description have a particular flavour, too: Rosalita is verdant but thorny, silken-petaled, fast-growing, fades in a strong sun, but fills the garden with wonder under the moonlight. I didn't actually *call* you a flower, but I may as well have.

11rosalita

Aw, shucks! I'm blushing. I'm more of a weed than a rose.

I'm a little amazed that I was as close as I was on some of it, but your translation really pulled it all together. And "solitary pleasure" — sorry I missed that! That Shakespeare was a bawdy fellow, eh?

I tried reading it aloud, and mostly felt stupid. I'm going to keep doing that, though, because I think it will help to hear the unfamiliar language as much as read it. We'll see.

Seventeen procreation sonnets! I'm not sure I can take the heat. :)

If there are any lurkers out there who would like to comment or ask Cyn questions, please go right ahead. I'll be back tomorrow evening to post the next sonnet. Here's a sneak preview: The first line is "When forty winters shall beseige thy brow" — I suppose that was quite old in Shakespeare's time, but to me that's when life is just getting started!

I'm a little amazed that I was as close as I was on some of it, but your translation really pulled it all together. And "solitary pleasure" — sorry I missed that! That Shakespeare was a bawdy fellow, eh?

I tried reading it aloud, and mostly felt stupid. I'm going to keep doing that, though, because I think it will help to hear the unfamiliar language as much as read it. We'll see.

Seventeen procreation sonnets! I'm not sure I can take the heat. :)

If there are any lurkers out there who would like to comment or ask Cyn questions, please go right ahead. I'll be back tomorrow evening to post the next sonnet. Here's a sneak preview: The first line is "When forty winters shall beseige thy brow" — I suppose that was quite old in Shakespeare's time, but to me that's when life is just getting started!

12SqueakyChu

Unlurking for just a minute to say I'm loving this! I, too, could make neither heads nor tales of that sonnet until Cynara "translated" it. Then, when I reread it, I couldn't figure out how it made no sense to me in the first reading but all became clear afterward. :)

13Cynara

sorry I missed that!

There is no reason for anyone to know that "bud" had some phallic connotations to the Elizabethans; I certainly didn't know. I'm looking up notes on these, you know!

I tried reading it aloud,

That's wonderful. Keep doing it, if you like! Shakespeare often sounds luscious when read aloud, and it's part of the fun. If I come across a poem I love, I have to read it out loud (or at least whisper it).

I'm not sure I can take the heat.

I don't want to oversell this, but we haven't seen anything yet. Wait until he starts talking about his Dark Ladye.

"When forty winters shall beseige thy brow"

That's a great first line. And it's in perfect iambic pentameter, too.... It's a funny thing about iambic that it often sounds like perfectly natural speech, unless you're looking for it.

when I reread it, I couldn't figure out how it made no sense to me in the first reading but all became clear afterward. :)

Hi, Madeline! Lovely to see you here.

That is not a simple sonnet. I would have found the final line really tough to figure out: "To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee." Really, Will? I think he was having an off day. It did happen.

Part of your difficulty might be the transposition of the words, which poets pulled all the time, to make the rhymes and rhythms turn out right. W.S. would never have said "or else this glutton be" to a friend in the pub - he would have said "or else you will be like this glutton", but it's hard to find a poetic rhyme for "glutton." Mutton? Button?

You might find the original edition's spellings interesting, too:

There is no reason for anyone to know that "bud" had some phallic connotations to the Elizabethans; I certainly didn't know. I'm looking up notes on these, you know!

I tried reading it aloud,

That's wonderful. Keep doing it, if you like! Shakespeare often sounds luscious when read aloud, and it's part of the fun. If I come across a poem I love, I have to read it out loud (or at least whisper it).

I'm not sure I can take the heat.

I don't want to oversell this, but we haven't seen anything yet. Wait until he starts talking about his Dark Ladye.

"When forty winters shall beseige thy brow"

That's a great first line. And it's in perfect iambic pentameter, too.... It's a funny thing about iambic that it often sounds like perfectly natural speech, unless you're looking for it.

when I reread it, I couldn't figure out how it made no sense to me in the first reading but all became clear afterward. :)

Hi, Madeline! Lovely to see you here.

That is not a simple sonnet. I would have found the final line really tough to figure out: "To eat the world's due, by the grave and thee." Really, Will? I think he was having an off day. It did happen.

Part of your difficulty might be the transposition of the words, which poets pulled all the time, to make the rhymes and rhythms turn out right. W.S. would never have said "or else this glutton be" to a friend in the pub - he would have said "or else you will be like this glutton", but it's hard to find a poetic rhyme for "glutton." Mutton? Button?

You might find the original edition's spellings interesting, too:

15Deern

Delurking to say that I love this thread! I agree that #1 is not among the strongest, it doesn't (imo) even sound that great when read aloud. I love #2 though, looking forward to the comments.

16CDVicarage

I shall be lurking (and perhaps commenting) too. This is wonderful so far. I feel I'm getting the benefit without doing any of the work, so thank you Rosalita and Cynara!

17SqueakyChu

> 13

Part of your difficulty might be the transposition of the words

That's for sure! I'll keep that idea in mind as you and rosalita proceed.

I'm familiar with the strange form of the letter "s" from reading old German printing which used similar lettering.

*goes back into lurkdom*

Part of your difficulty might be the transposition of the words

That's for sure! I'll keep that idea in mind as you and rosalita proceed.

I'm familiar with the strange form of the letter "s" from reading old German printing which used similar lettering.

*goes back into lurkdom*

18Cynara

>17 SqueakyChu:

I also like "fewell" for "fuel." English spelling was more fun before the dictionary.

I also like "fewell" for "fuel." English spelling was more fun before the dictionary.

19rosalita

I've always wondered how they decided when to use the regular s and when to use the long s. Was it just personal whim, or was there a pattern?

21Deern

In Germany a different cursive has been used till WWII, I still learned (voluntarily) to read and write it because it's so pretty. It also had 2 forms of 's', one was used at the end of a word only. Looks like it is the same pattern here, 's' being used with 'eyes' and 'lies' and the long one in all other cases.

There was even a third form (which still exists today and is part of my last name) which was used for two 's' in a row ==> 'ß' (looks like the Greek beta), the 'sharp s' . So maybe we'll get to see another variety here as well - Shakespeare's English is still quite related to German.

There was even a third form (which still exists today and is part of my last name) which was used for two 's' in a row ==> 'ß' (looks like the Greek beta), the 'sharp s' . So maybe we'll get to see another variety here as well - Shakespeare's English is still quite related to German.

22gennyt

#20 Yes, the long form of 's' originates in the hand-written letter form which at the beginning or in the middle of words would often be joined on to the next letter - the long form lends itself to such ligatures more readily than the regular 's'. Although in printed typeface the letters are normally separate because each is made by a separate piece of type, there are a few common letter combinations that were made into single type pieces in imitation of how they would have been written by hand - in the image above I think I can see several 'st' ligatures, as well as a fancy 'ct' ligature.

#21 And the German double ss which looks a bit like Greek beta is actually a ligature with a long s joined to a short one.

I'm not sure at what date the long 's' stopped being used in the printing of English - my knowledge is in the earlier periods rather than after this. Anyone know?

#21 And the German double ss which looks a bit like Greek beta is actually a ligature with a long s joined to a short one.

I'm not sure at what date the long 's' stopped being used in the printing of English - my knowledge is in the earlier periods rather than after this. Anyone know?

23Dejah_Thoris

*lurk, lurk, lurk*

25rosalita

Great discussion! I'm not gonna lie; while I enjoy looking at old texts that have the archaic letter shapes and spellings, I am very glad not to be fighting these two issues along with trying to figure out what the heck ol' Will is trying to say! Now, on to Sonnet 2:

Thanks to Cyn's expert tutoring for Sonnet 1, this one seemed much less impenetrable. It seems Will is continuing his exhortation to his beautiful friend to get on and make some babies for crying out loud, so that his beauty may live on.

1. In the fourth line, my book clearly says "tottered" though "tattered" seems a much more natural word. I'm not sure if this is another of those arbitrary spellings, or if Shakespeare really intended to conjure an image of a weed "moving in a feeble or unsteady way" rather than "torn, old, and in generally poor condition". I guess either one works when you come right down to it.

2. I touched on this briefly in an earlier message, but I must say I find it comical that 40 is the age at which Shakespeare considers that his friend will be so old and decrepit, with "deep trenches in thy beauty's field". Obviously they didn't have Botox back in the day. :)

When forty winters shall besiege thy brow(There's no illustration on this sonnet's page.)

And dig deep trenches in thy beauty's field

Thy youth's proud livery, so gazed on now,

Will be a tottered weed of small worth held.

Then being asked where all beauty lies—

Where all the treasure of thy lusty days—

To say within thine own deep-sunken eyes

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise.

How much more praise deserved thy beauty's use,

If thou couldst answer, "This fair child of mine

Shall sum my count and make my old excuse" —

Proving his beauty by succession thine.

This were to be new made when thou art old

And see thy blood warm when thou feel'st it cold.

Thanks to Cyn's expert tutoring for Sonnet 1, this one seemed much less impenetrable. It seems Will is continuing his exhortation to his beautiful friend to get on and make some babies for crying out loud, so that his beauty may live on.

1. In the fourth line, my book clearly says "tottered" though "tattered" seems a much more natural word. I'm not sure if this is another of those arbitrary spellings, or if Shakespeare really intended to conjure an image of a weed "moving in a feeble or unsteady way" rather than "torn, old, and in generally poor condition". I guess either one works when you come right down to it.

2. I touched on this briefly in an earlier message, but I must say I find it comical that 40 is the age at which Shakespeare considers that his friend will be so old and decrepit, with "deep trenches in thy beauty's field". Obviously they didn't have Botox back in the day. :)

26Cynara

While I would like to take credit for the sun breaking through the clouds, etc., I think it's just that Will managed to write a sonnet that makes a bit more sense here. Also, this one is rather lovely, I think. It has a little of that combined epic sweep and intimacy that makes his best stuff so shatteringly good.

Tattered, tottered, and weeds

This will all get a bit clearer when you find out that "weeds" are clothes. Have you ever heard of an old woman's black clothes being called "widow's weeds"? Most editions I've seen say "tattered." An original misprint? An alternate spelling?

Either way, he's saying that the Young Man's (metaphorical) livery*, his beauty, will be tattered by age into raggedy clothes.

*His uniform. Livery was normally worn by servants; if your master's heraldic colours were red and white, you'd wear red and white livery. In this case, Shakes. is saying that the young man's looks are his "livery".

Old at 40

Elizabethans didn't live as long as we do. However, the infant mortality rate was far higher than ours, which tends to skew the average lifespan data; if you made it into your teens, you would quite possibly make it into your sixties or seventies, according to several (gaily uncited, so unreliable) sources I've found online. It's possible that Shakespeare is gently teasing his young friend here; Will is probably his thirties** when he's writing this, so forty may not seem so old to him.

** When Francis Meres wrote a "survey" of poetry and literature he mentioned W.S. and "his sugared sonnets among his private friends." Shakespeare was about 34 then.

We don't know exactly when this poem was written - it could have been years earlier or later - but at the time of writing he's a) old enough to be handing out advice to men of marriageable age, and b) younger than forty-five, when the sonnet was first published.

Dodgy Bits

According to one source I read, all that

" ...treasure of thy lusty days—

To say within thine own deep-sunken eyes

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise."

business is a series of thinly veiled allusions to self-pleasuring. However, to hear this source tell it, all seventeen sonnets are a series of thinly veiled condemnations of masturbation. I'm not sure I believe it; it all sounds too desperately Victorian to me. They were the ones with all the weird onanism complexes, and anyway I'm very suspicious of these overarching explanations of what the sonnets "really" mean. That works for some authors, but this particular one doesn't ring true. Will is far more interested in themes of youth, beauty, fertility, and the inevitability of age, if you ask me.

Tattered, tottered, and weeds

This will all get a bit clearer when you find out that "weeds" are clothes. Have you ever heard of an old woman's black clothes being called "widow's weeds"? Most editions I've seen say "tattered." An original misprint? An alternate spelling?

Either way, he's saying that the Young Man's (metaphorical) livery*, his beauty, will be tattered by age into raggedy clothes.

*His uniform. Livery was normally worn by servants; if your master's heraldic colours were red and white, you'd wear red and white livery. In this case, Shakes. is saying that the young man's looks are his "livery".

Old at 40

Elizabethans didn't live as long as we do. However, the infant mortality rate was far higher than ours, which tends to skew the average lifespan data; if you made it into your teens, you would quite possibly make it into your sixties or seventies, according to several (gaily uncited, so unreliable) sources I've found online. It's possible that Shakespeare is gently teasing his young friend here; Will is probably his thirties** when he's writing this, so forty may not seem so old to him.

** When Francis Meres wrote a "survey" of poetry and literature he mentioned W.S. and "his sugared sonnets among his private friends." Shakespeare was about 34 then.

We don't know exactly when this poem was written - it could have been years earlier or later - but at the time of writing he's a) old enough to be handing out advice to men of marriageable age, and b) younger than forty-five, when the sonnet was first published.

Dodgy Bits

According to one source I read, all that

" ...treasure of thy lusty days—

To say within thine own deep-sunken eyes

Were an all-eating shame and thriftless praise."

business is a series of thinly veiled allusions to self-pleasuring. However, to hear this source tell it, all seventeen sonnets are a series of thinly veiled condemnations of masturbation. I'm not sure I believe it; it all sounds too desperately Victorian to me. They were the ones with all the weird onanism complexes, and anyway I'm very suspicious of these overarching explanations of what the sonnets "really" mean. That works for some authors, but this particular one doesn't ring true. Will is far more interested in themes of youth, beauty, fertility, and the inevitability of age, if you ask me.

27Cynara

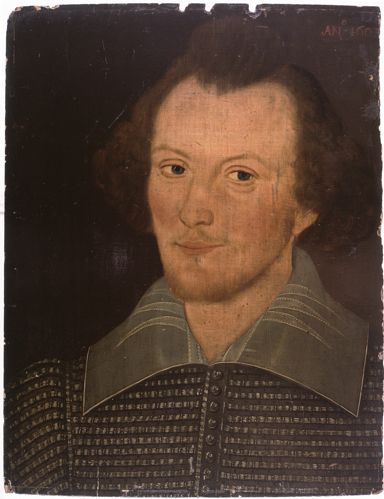

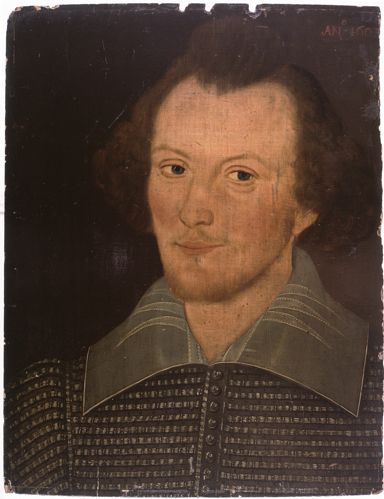

Speaking of gaily uncited things, I'd like to share my favourite slightly dodgy Shakespeare portrait.

Of course, all the good ones are unproven. The only one we're sure is of Shakespeare is the awful engraving in the front of the First Folio of his plays - and it looks like it was drawn from a description by an artist with a hangover:

Dreadful. Looks like poor Will's head is being served up on a platter. And the eyes. The longer you look at it, the worse it gets.

Here's the one I like:

Quite unproven. Turned up in an Ontario attic, and hasn't been disproven yet, so far as I know. Still, I love this Shakespeare. The warmth, the little smile and sidelong glance; it's not a great portrait, but it's a human being there, and our Will was that.

Of course, all the good ones are unproven. The only one we're sure is of Shakespeare is the awful engraving in the front of the First Folio of his plays - and it looks like it was drawn from a description by an artist with a hangover:

Dreadful. Looks like poor Will's head is being served up on a platter. And the eyes. The longer you look at it, the worse it gets.

Here's the one I like:

Quite unproven. Turned up in an Ontario attic, and hasn't been disproven yet, so far as I know. Still, I love this Shakespeare. The warmth, the little smile and sidelong glance; it's not a great portrait, but it's a human being there, and our Will was that.

29aulsmith

26: Onanism - could it be not so much a condemnation of masturbation as of having sex by oneself when one could be having sex with a partner -- especially the sonnet writer? Though I can't figure out how that relates to urging him to have children.

I took Shakespeare back in the dark ages when they just skipped the sonnets to the young men, even though my Shakespeare teacher was one of the outest gay men in our city, so I'm not up on Elizabethan homoerotic metaphors.

I took Shakespeare back in the dark ages when they just skipped the sonnets to the young men, even though my Shakespeare teacher was one of the outest gay men in our city, so I'm not up on Elizabethan homoerotic metaphors.

30Cynara

I think there's a suggested condemnation of masturbation as unproductive that in the first sonnet. It could be here, too, but I don't know enough about the exact implications of these words in early modern English. I suppose a less lazy woman could spend some time with an Oxford English Dictionary and come out better-educated. Maybe I'll look up "treasure", anyway, which my source claimed could refer to genitals or semen in this period. That might shed some light on other sonnets, anyway.

32rosalita

Cynara, I definitely prefer your favorite portrait of Shakespeare! The one we've all seen really makes him look odd. In addition to the platter/collar and the creepy eyes, there's the whole hairline issue. It looks like someone hung a hair curtain on the back of a bald man's head.

Regarding weeds, I have heard of widow's weeds but didn't make the connection in this context. That does make a great deal of sense, especially paired with livery in the next line. I'm leaning toward my edition being a typo, and the proper word being tattered. I prefer it, anyway!

Aulsmith, I thought of the "don't masturbate; have sex with me" angle, but like you I couldn't figure out how that would result in children. :)

So great to see so many people commenting and bringing interesting info to the discussion. It's terrific! Keep it up; I'll be back tomorrow with Sonnet 3. And judging by the first line, we've got some more beauty obsession in store for us:

Regarding weeds, I have heard of widow's weeds but didn't make the connection in this context. That does make a great deal of sense, especially paired with livery in the next line. I'm leaning toward my edition being a typo, and the proper word being tattered. I prefer it, anyway!

Aulsmith, I thought of the "don't masturbate; have sex with me" angle, but like you I couldn't figure out how that would result in children. :)

So great to see so many people commenting and bringing interesting info to the discussion. It's terrific! Keep it up; I'll be back tomorrow with Sonnet 3. And judging by the first line, we've got some more beauty obsession in store for us:

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest,

34rosalita

Before I get into Sonnet 3, I wanted to say that even if we move on to the next sonnet, don't feel you can't chime in with some thoughts on an earlier posting. I realize not everyone is hanging on every post, especially on such a beautiful summer-like March day (at least here in Iowa; I hope it's nice wherever you are, too).

Now, on to Sonnet 3:

Whew! That last line seems to be about the most direct Shakespeare has been in his "go forth and multiply" exhortation. Die single and thine image dies with thee. Even I can figure that one out!

I guess you don't have to be Catholic or Jewish to resort to guilting someone into doing something they don't want to do. I mean, really: Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee / Calls back the lovely April of her prime? Way to bring mama into the argument, Will.

And there may have been some ambiguity in the earlier sonnets about whether "bud" or "treasure" were referring to self-pleasure, but there's little ambiguity in she so fair whose uneared womb / Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry. Putting aside the notion of comparing women to livestock, that's pretty straightforward sexual metaphor, I think.

I'm really starting to wonder why Shakespeare is so hell-bent on his friend having a baby. I assume by the time this was written Will himself was a father. Was he matchmaking his friend with someone in particular? Or was he worried his friend's reputation would suffer, if he continued in his bachelor ways? Or perhaps both their reputations would suffer if he kept hanging out alone with a beautiful single man? Hmmm.

Now, on to Sonnet 3:

Look in thy glass and tell the face thou viewest,The illustration on this page is, unsurprisingly, of a mirror.

Now is the time that face should form another,

Whose fresh repair if now thou not renewest,

Thou dost beguile the world, unbless some mother.

For where is she so fair whose uneared womb

Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

Or who is he so fond will be the tomb

Of his self-love to stop posterity?

Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee

Calls back the lovely April of her prime;

So thou through windows of thine age shalt see,

Despite of wrinkles, this thy golden time.

But if thou live remembered not to be,

Die single and thine image dies with thee.

Whew! That last line seems to be about the most direct Shakespeare has been in his "go forth and multiply" exhortation. Die single and thine image dies with thee. Even I can figure that one out!

I guess you don't have to be Catholic or Jewish to resort to guilting someone into doing something they don't want to do. I mean, really: Thou art thy mother's glass, and she in thee / Calls back the lovely April of her prime? Way to bring mama into the argument, Will.

And there may have been some ambiguity in the earlier sonnets about whether "bud" or "treasure" were referring to self-pleasure, but there's little ambiguity in she so fair whose uneared womb / Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry. Putting aside the notion of comparing women to livestock, that's pretty straightforward sexual metaphor, I think.

I'm really starting to wonder why Shakespeare is so hell-bent on his friend having a baby. I assume by the time this was written Will himself was a father. Was he matchmaking his friend with someone in particular? Or was he worried his friend's reputation would suffer, if he continued in his bachelor ways? Or perhaps both their reputations would suffer if he kept hanging out alone with a beautiful single man? Hmmm.

35Cynara

Way to bring mama into the argument, Will.

LOL.

I'm really starting to wonder why Shakespeare is so hell-bent on his friend having a baby.

You know, I was wondering exactly the same thing last night. I was reading ahead a bit and eventually I started thinking "move on, Will, you got your point across."

I can see one or two poems on the subject, but seventeen? Yes, Will is a father by this point (three kids!), but does that really explain it? What, was his friend going to be tarred and feathered by outraged babymamma relatives? Was he the heir to a great estate that was entailed upon the male line (if legal entail isn't anachronistic for 1600 or so)?

Perhaps these sonnets were commissioned by an anxious father who was wondering if his son was ever going to settle down. Maybe Shakespeare set himself a challenge: "how many poems can I write about one limited topic...." We'll never know.

For where is she so fair whose uneared womb/Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

The metaphor here is women=farmland. "Uneared" means "unploughed", and "tillage" also essentially means ploughing. "Husbandry" is of course a little play on words between farming (husbandry) and being a husband.

The Volta

In each sonnet, there's a volta or turning, where the tone switches. Normally, the first three quatrains (groups of four lines) set up a problem, and the couplet solves it (or comes at it from a different angle). Sometimes it's given away by a line beginning "But..." or "And yet...."

Occasionally, it'll come after the first two quatrains (e.g. in Italian-style sonnets), but Shakespeare usually can't resist the drama of sticking it to us with the last couplet:

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

or:

Yet do not so; but since I am near slain,

Kill me outright with looks, and rid my pain.

LOL.

I'm really starting to wonder why Shakespeare is so hell-bent on his friend having a baby.

You know, I was wondering exactly the same thing last night. I was reading ahead a bit and eventually I started thinking "move on, Will, you got your point across."

I can see one or two poems on the subject, but seventeen? Yes, Will is a father by this point (three kids!), but does that really explain it? What, was his friend going to be tarred and feathered by outraged babymamma relatives? Was he the heir to a great estate that was entailed upon the male line (if legal entail isn't anachronistic for 1600 or so)?

Perhaps these sonnets were commissioned by an anxious father who was wondering if his son was ever going to settle down. Maybe Shakespeare set himself a challenge: "how many poems can I write about one limited topic...." We'll never know.

For where is she so fair whose uneared womb/Disdains the tillage of thy husbandry?

The metaphor here is women=farmland. "Uneared" means "unploughed", and "tillage" also essentially means ploughing. "Husbandry" is of course a little play on words between farming (husbandry) and being a husband.

The Volta

In each sonnet, there's a volta or turning, where the tone switches. Normally, the first three quatrains (groups of four lines) set up a problem, and the couplet solves it (or comes at it from a different angle). Sometimes it's given away by a line beginning "But..." or "And yet...."

Occasionally, it'll come after the first two quatrains (e.g. in Italian-style sonnets), but Shakespeare usually can't resist the drama of sticking it to us with the last couplet:

So long as men can breathe, or eyes can see,

So long lives this, and this gives life to thee.

or:

Yet do not so; but since I am near slain,

Kill me outright with looks, and rid my pain.

36rosalita

OK, so women=farmland and not livestock. I thought it was funny because I'm sure we've all heard crude men refer to "plowing that field". Somehow, I don't think they are intentionally harking back to Shakespeare when they say it!

Thanks for the new term, volta. I'll be on the lookout through the rest of the sonnets to see where Shakespeare uses it. So far, it definitely seems that last couplet is his favorite spot.

Thanks for the new term, volta. I'll be on the lookout through the rest of the sonnets to see where Shakespeare uses it. So far, it definitely seems that last couplet is his favorite spot.

38Cynara

"plowing that field".

It is a rather... earthy... metaphor. Ba-dum ching!

I'm so sorry. I don't know what came over me.

>37 jnwelch:

Glad you're enjoying it! I'm so happy so many people are following along. Feel free to chip in or ask a question.

It is a rather... earthy... metaphor. Ba-dum ching!

I'm so sorry. I don't know what came over me.

>37 jnwelch:

Glad you're enjoying it! I'm so happy so many people are following along. Feel free to chip in or ask a question.

39Deern

I read somewhere (don't remember where and it's probably just another theory) that those first 17 sonnets were in fact some kind of commissioned work, ordered by the mother of the 'fair youth'. The objective was to make him aware of his duty to finally settle down and start a family. My idea is that the official dedication applies to those first sonnets, but might not necessarily apply to the rest of them.

40Linda92007

I don't have anything of consequence to add to the discussion, but did want you both to know that I am following along, enjoying it immensely, and learning a great deal. This was a wonderful idea.

41rosalita

Sonnet 4, boys and girls!

My first reaction, as I read this sonnet aloud, was that it's … well, ugly sounding. There are a lot of harsh-sounding consonants that seem to match the exasperated, even angry tone, of the writer, and the rhythm of the lines seems off somehow. He really sounds ticked off here that his pleas to go forth and multiply are being ignored, doesn't he? Our poet seems to have progressed from entreaty to anger in this one.

It's odd to me that he calls the Fair Youth "unthrifty" in Line 1, and then berates him for being the exact opposite: "niggard," "usurer," etc. How can he be both wasteful and stingy with his beauty? And isn't a usurer like a loan shark — someone who loans money at unreasonably high interest rates? How does that fit with the wasteful/stingy tags?

I'm probably reading this all wrong. I know we are only four sonnets in, but I'd say this one is my least favorite so far. Now, all I need is for Cynara to explain to me why I'm wrong!

Unthrifty loveliness, why dost thou spendThe illustration with this sonnet is of a small velvet drawstring bag of the type used as moneypurses back in Shakespeare's day.

Upon thyself thy beauty's legacy?

Nature's bequest gives nothing but doth lend,

And being frank she lends to those are free.

Then beauteous niggard why dost thou abuse

The bounteous lárgess given thee to give?

Profitless usurer, why dost thou use

So great a sum of sums yet canst not live?

For having traffic with thyself alone,

Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive.

Then how when nature calls thee to be gone,

What ácceptable audit canst thou leave?

Thy unused beauty must be tombed with thee,

Which usèd lives th'executor to be.

My first reaction, as I read this sonnet aloud, was that it's … well, ugly sounding. There are a lot of harsh-sounding consonants that seem to match the exasperated, even angry tone, of the writer, and the rhythm of the lines seems off somehow. He really sounds ticked off here that his pleas to go forth and multiply are being ignored, doesn't he? Our poet seems to have progressed from entreaty to anger in this one.

It's odd to me that he calls the Fair Youth "unthrifty" in Line 1, and then berates him for being the exact opposite: "niggard," "usurer," etc. How can he be both wasteful and stingy with his beauty? And isn't a usurer like a loan shark — someone who loans money at unreasonably high interest rates? How does that fit with the wasteful/stingy tags?

I'm probably reading this all wrong. I know we are only four sonnets in, but I'd say this one is my least favorite so far. Now, all I need is for Cynara to explain to me why I'm wrong!

42Cynara

There's a distinct note of frustration here, isn't there? All those rhetorical questions and hissy 's' words. I think Shakespeare has done this kind of paradoxical scolding in earlier sonnets, too (And tender churl mak'st waste in niggarding.) The young man is wasting his beauty because he's hoarding it all to himself; if he invested it by marrying, then he'd be making more beauty by having kids.

I think I remember John Donne trying something similar in a get-her-into-bed poem; he posits that by having sex with him, the lady will be *increasing* the amount of virginity in the world by having children. Uh-huh, John? How did that work for you?

I believe "usurer" simply meant a moneylender in this period; you couldn't borrow money from banks, and if your friends had cut you off, he was the only option. It wasn't considered a Christian - or classy - occupation, so there's a bit of a sting in being called a "profitless usurer". Not only is he comparing the the young man to a moneylender, he's comparing him to an unsuccessful one.

While this isn't the prettiest sonnet, I do admire the extended money=beauty metaphor. I think No. 1 is still my least favourite, though none of these is exactly his greatest.

the rhythm of the lines seems off somehow

Is there any line in particular that strikes you that way?

I'm probably reading this all wrong.

Obviously not. You're doing well! You're reading it with your eyes and brain, which is the right way. :-)

I think I remember John Donne trying something similar in a get-her-into-bed poem; he posits that by having sex with him, the lady will be *increasing* the amount of virginity in the world by having children. Uh-huh, John? How did that work for you?

I believe "usurer" simply meant a moneylender in this period; you couldn't borrow money from banks, and if your friends had cut you off, he was the only option. It wasn't considered a Christian - or classy - occupation, so there's a bit of a sting in being called a "profitless usurer". Not only is he comparing the the young man to a moneylender, he's comparing him to an unsuccessful one.

While this isn't the prettiest sonnet, I do admire the extended money=beauty metaphor. I think No. 1 is still my least favourite, though none of these is exactly his greatest.

the rhythm of the lines seems off somehow

Is there any line in particular that strikes you that way?

I'm probably reading this all wrong.

Obviously not. You're doing well! You're reading it with your eyes and brain, which is the right way. :-)

44lyzard

>>#41

I think the seeming contradiction in "thrifty" is that the word is used in the sense of planning for the future - he is "unthrifty" because he refuses to do anything but live in the here and now. Likewise "profitless usurer" - he's not getting a return on his investment.

For having traffic with thyself alone

That criticism seems clear enough. :)

Sorry - just butting in in passing - carry on!

I think the seeming contradiction in "thrifty" is that the word is used in the sense of planning for the future - he is "unthrifty" because he refuses to do anything but live in the here and now. Likewise "profitless usurer" - he's not getting a return on his investment.

For having traffic with thyself alone

That criticism seems clear enough. :)

Sorry - just butting in in passing - carry on!

45Cynara

//For having traffic with thyself alone

That criticism seems clear enough. :)//

Honestly? I pulled out my Oxford English Dictionary to see if the obscene meaning of "spend" was current in this period. Hard to say, really; it wasn't until 1662 that filthy boy Samuel Pepys wrote it down in his diary. Sixty-odd years is a bit of a jump, but I can't help wondering....

That criticism seems clear enough. :)//

Honestly? I pulled out my Oxford English Dictionary to see if the obscene meaning of "spend" was current in this period. Hard to say, really; it wasn't until 1662 that filthy boy Samuel Pepys wrote it down in his diary. Sixty-odd years is a bit of a jump, but I can't help wondering....

46rosalita

the rhythm of the lines seems off somehow

Is there any line in particular that strikes you that way?

Re-reading it, I think it's not the rhythm of the lines as they are written, but the difficulty I had reading them smoothly with all the doths and dosts, and thous and cansts scattered about, along with the switched-up word order in some lines. (I mean, really: Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive.) I stumbled quite a bit as I was reading it aloud, and decided to blame Will instead of myself. :)

On a semi-related note, what is the point of the accent marks on the 'a' in largess and acceptable? Should I have been reading those with a different emphasis than I would normally, or is it that our normal pronunciation today was not normal back then and so needed the accent marks? I do get that the accented e in 'used' means it should be read as two syllables and not the more customary one.

That definition of usurer makes much more sense in the context of the sonnet. And now that you point it out, the money/beauty metaphor is very nice. I bet if I practiced reading it aloud until I could do it smoothly, I might even learn to like it. :)

Is there any line in particular that strikes you that way?

Re-reading it, I think it's not the rhythm of the lines as they are written, but the difficulty I had reading them smoothly with all the doths and dosts, and thous and cansts scattered about, along with the switched-up word order in some lines. (I mean, really: Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive.) I stumbled quite a bit as I was reading it aloud, and decided to blame Will instead of myself. :)

On a semi-related note, what is the point of the accent marks on the 'a' in largess and acceptable? Should I have been reading those with a different emphasis than I would normally, or is it that our normal pronunciation today was not normal back then and so needed the accent marks? I do get that the accented e in 'used' means it should be read as two syllables and not the more customary one.

That definition of usurer makes much more sense in the context of the sonnet. And now that you point it out, the money/beauty metaphor is very nice. I bet if I practiced reading it aloud until I could do it smoothly, I might even learn to like it. :)

47Cynara

(I mean, really: Thou of thyself thy sweet self dost deceive.?)

Ha! The Elizabethans thought that kind of stuff was desperately witty, but it hasn't aged well. I think there's a part in Hamlet where he & Rosencrantz & Guildenstern go on like this for a while, but it's often cut because audiences have no clue what they're prattling on about.

what is the point of the accent marks on the 'a' in largess and acceptable

I was sort of hoping you wouldn't ask. If I had to guess, I'd say they're marks to show stress, like the one in "used", but that doesn't really work for "acceptable." Does anyone else know?

I bet if I practiced reading it aloud

If I did that, I'd read it in high dudgeon: just tear a strip off of him.

By the way, "niggard," which does make me flinch a little every time I read it, is totally unrelated to the similar-sounding slur; it's from a Scandinavian root, not from Latin.

Ha! The Elizabethans thought that kind of stuff was desperately witty, but it hasn't aged well. I think there's a part in Hamlet where he & Rosencrantz & Guildenstern go on like this for a while, but it's often cut because audiences have no clue what they're prattling on about.

what is the point of the accent marks on the 'a' in largess and acceptable

I was sort of hoping you wouldn't ask. If I had to guess, I'd say they're marks to show stress, like the one in "used", but that doesn't really work for "acceptable." Does anyone else know?

I bet if I practiced reading it aloud

If I did that, I'd read it in high dudgeon: just tear a strip off of him.

By the way, "niggard," which does make me flinch a little every time I read it, is totally unrelated to the similar-sounding slur; it's from a Scandinavian root, not from Latin.

48rosalita

I remember looking up "niggard" once a few years ago in the context of some other book. I was relieved to learn that it wasn't what I thought it was.

49rosalita

On to Number 5 …

This sonnet seems like a bit of a departure from 1-4. It's still about how time fades beauty, but it's completely abstract; there is no 'thou' that it is addressed to, or that nature's beauty is compared to. Where the voice of the other sonnets seems exasperated or pleading, this one just seems a bit melancholy.

I had to read it through a few times aloud to catch the hang of its rhythm, especially in the lines that seem to want to be read straight through with no pause at the end of a line (in particular, For never-resting time leads summer on / To hideous winter and confounds him there). Once I got the rhythm down, I started to appreciate some of the lovely imagery (like that line I just quoted). I picture time as a gaily dressed beautiful woman flitting through the woods with gauzy scarves catching the sunlight as they trail behind her, and summer as a young man in bold pursuit only to find when they reach a clearing that she has led him into a trap where winter lies waiting as a grizzled old man (her father with a shotgun, maybe).

I also love the phrase beauty o'ersnowed and bareness everywhere; I must find a way to work that into random conversations.

What is summer's distillation which is a liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass? All I could come up with was whiskey or some other spirit, but as I wrote those words I thought perhaps it's meant to be perfume? It comes up again in the couplet, where it is more specifically addressed as flow'rs distilled.

Also in the couplet, I am assuming 'leese' is an alternate form of 'lose'? That's one I've never seen before.

What did everyone else think?

Those hours that with gentle work did frameNo illustration.

The lovely gaze where every eye doth dwell

Will play the tyrants to the very same

And that unfair which fairly doth excel;

For never-resting time leads summer on

To hideous winter and confounds him there,

Sap checked with frost and lusty leaves quite gone,

Beauty o'ersnowed and bareness everywhere.

Then were not summer's distillation left

A liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass,

Beauty's effect with beauty were bereft,

Nor it nor no remembrance what it was.

But flow'rs distilled, though they with winter meet,

Leese but their show, their substance still lives sweet.

This sonnet seems like a bit of a departure from 1-4. It's still about how time fades beauty, but it's completely abstract; there is no 'thou' that it is addressed to, or that nature's beauty is compared to. Where the voice of the other sonnets seems exasperated or pleading, this one just seems a bit melancholy.

I had to read it through a few times aloud to catch the hang of its rhythm, especially in the lines that seem to want to be read straight through with no pause at the end of a line (in particular, For never-resting time leads summer on / To hideous winter and confounds him there). Once I got the rhythm down, I started to appreciate some of the lovely imagery (like that line I just quoted). I picture time as a gaily dressed beautiful woman flitting through the woods with gauzy scarves catching the sunlight as they trail behind her, and summer as a young man in bold pursuit only to find when they reach a clearing that she has led him into a trap where winter lies waiting as a grizzled old man (her father with a shotgun, maybe).

I also love the phrase beauty o'ersnowed and bareness everywhere; I must find a way to work that into random conversations.

What is summer's distillation which is a liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass? All I could come up with was whiskey or some other spirit, but as I wrote those words I thought perhaps it's meant to be perfume? It comes up again in the couplet, where it is more specifically addressed as flow'rs distilled.

Also in the couplet, I am assuming 'leese' is an alternate form of 'lose'? That's one I've never seen before.

What did everyone else think?

50Cynara

I picture time as a gaily dressed beautiful woman flitting through the woods with gauzy scarves catching the sunlight as they trail behind her, and summer as a young man in bold pursuit only to find when they reach a clearing that she has led him into a trap where winter lies waiting as a grizzled old man (her father with a shotgun, maybe).

So. Cool. I love it.

perhaps it's meant to be perfume?

'leese' is an alternate form of 'lose'?

Yes and yes.

This is probably my favourite so far. It could be a coincidence that Will is barely hinting at the have-babies-immediately theme; if I didn't know the context, it wouldn't occur to me at all. There are some truly gorgeous images, particularly the ones you mentioned. I also like "distillation" and "a liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass." There are a few infelicities, I think ("Nor it nor no remembrance what it was"), but I love the evocation of winter, and summer kept in a glass phial.

So. Cool. I love it.

perhaps it's meant to be perfume?

'leese' is an alternate form of 'lose'?

Yes and yes.

This is probably my favourite so far. It could be a coincidence that Will is barely hinting at the have-babies-immediately theme; if I didn't know the context, it wouldn't occur to me at all. There are some truly gorgeous images, particularly the ones you mentioned. I also like "distillation" and "a liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass." There are a few infelicities, I think ("Nor it nor no remembrance what it was"), but I love the evocation of winter, and summer kept in a glass phial.

51rosalita

My favorite, too, Cyn! And yes, I think part of my fondness is that the baby-making theme is not so front-and-center. Really, if you didn't know that was the theme for the first 17 sonnets, you would think this was just a beautiful poem about the passing of the seasons.

I'm laughing at myself a little that my mind went immediately to whiskey and not perfume when I read the line about summer distilled into a liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass. I guess it was a harder day at work than I realized!

It's just a lovely poem all around!

I'm laughing at myself a little that my mind went immediately to whiskey and not perfume when I read the line about summer distilled into a liquid prisoner pent in walls of glass. I guess it was a harder day at work than I realized!

It's just a lovely poem all around!

52Cynara

/ my mind went immediately to whiskey

"We were reading that Shakespeare sonnet... you know, the one about tequila...."

"We were reading that Shakespeare sonnet... you know, the one about tequila...."

55rosalita

Number 6 coming right up …

So. This sonnet reads like Part 2 of Sonnet 5, where the procreation theme returns with a bang (pardon the pun) and mates with (sorry again) the summer-into-winter theme. It even starts as if it is the continuation of a conversation: Then let not winter's ragged hand deface / In thee thy summer ere thou be distilled.