***REGION 25: Europe VII

ConversazioniReading Globally

Iscriviti a LibraryThing per pubblicare un messaggio.

1avaland

If you have not read the information on the master thread regarding the intent of these regional threads, please do this first.

***25. Europe VII: Spain, Portugal, Andorra, Gibraltar

***25. Europe VII: Spain, Portugal, Andorra, Gibraltar

2arubabookwoman

PORTUGAL

The Maias by Eca de Queiros

This magnificent 19th century novel has been called, 'The greatest book by Portugal's greatest novelist,' by Jose Saramago. Harold Bloom called it, 'one of the most impressive European novels of the nineteenth century, fully comparable to the most inspired novels of the great Russian, French, Italian and English masters of prose fiction.' I had never heard of this book or its author before I picked it up. I am so glad I did, and I will be reading more of de Queiros.

The book reminds me of Buddenbrooks, so for anyone who has read and loved Buddenbrooks that might be recommendation enough. The family in The Maias is much smaller than that in Buddenbrooks. After his mother runs away with her lover, and his father's tragic death, Carlos da Maia is raised by his wealthy grandfather. He studies at medical school, and as a young man becomes a dilettante in Lisbon society. Ultimately, he faces a tragedy that will form his character for the rest of his life.

What I loved about this book are the characters. The love Carlos's grandfather has for Carlos permeates the story. He is there behind the scenes, not intrusive, but his love is boundless. It takes Carlos a long time to realize this. The story of Carlos's friendship with Ega, another happy-go-lucky man-about the town is also beautifully portrayed. We should all be so lucky as to have such a friendship in our lives

The Maias by Eca de Queiros

This magnificent 19th century novel has been called, 'The greatest book by Portugal's greatest novelist,' by Jose Saramago. Harold Bloom called it, 'one of the most impressive European novels of the nineteenth century, fully comparable to the most inspired novels of the great Russian, French, Italian and English masters of prose fiction.' I had never heard of this book or its author before I picked it up. I am so glad I did, and I will be reading more of de Queiros.

The book reminds me of Buddenbrooks, so for anyone who has read and loved Buddenbrooks that might be recommendation enough. The family in The Maias is much smaller than that in Buddenbrooks. After his mother runs away with her lover, and his father's tragic death, Carlos da Maia is raised by his wealthy grandfather. He studies at medical school, and as a young man becomes a dilettante in Lisbon society. Ultimately, he faces a tragedy that will form his character for the rest of his life.

What I loved about this book are the characters. The love Carlos's grandfather has for Carlos permeates the story. He is there behind the scenes, not intrusive, but his love is boundless. It takes Carlos a long time to realize this. The story of Carlos's friendship with Ega, another happy-go-lucky man-about the town is also beautifully portrayed. We should all be so lucky as to have such a friendship in our lives

3rebeccanyc

Another book that sounds interesting -- thanks. I adore Buddenbrooks.

4alalba

Spain

Todo es silencio by Manuel Rivas

Brentema, a small village on the coast in Galicia is the place where this story takes place. Fins, Leda and Brinco, the main characters, are children who live by the sea, learning from his elders that they must look, hear and keep silent if they want to survive. They also learn to respect the desires of Mariscal, who has made a fortune by smuggling and who rules the village. The novel follows the life of these characters from childhood to maturity and illustrates different aspects of life in the village always linked to the sea and to smuggling. The language in this book is very poetic and the author manages to convey well the atmosphere of the place, its mystery and its changing moods. This is a work in which there are many things which are not told but which are subtly insinuated, a great book!

Todo es silencio by Manuel Rivas

Brentema, a small village on the coast in Galicia is the place where this story takes place. Fins, Leda and Brinco, the main characters, are children who live by the sea, learning from his elders that they must look, hear and keep silent if they want to survive. They also learn to respect the desires of Mariscal, who has made a fortune by smuggling and who rules the village. The novel follows the life of these characters from childhood to maturity and illustrates different aspects of life in the village always linked to the sea and to smuggling. The language in this book is very poetic and the author manages to convey well the atmosphere of the place, its mystery and its changing moods. This is a work in which there are many things which are not told but which are subtly insinuated, a great book!

5kidzdoc

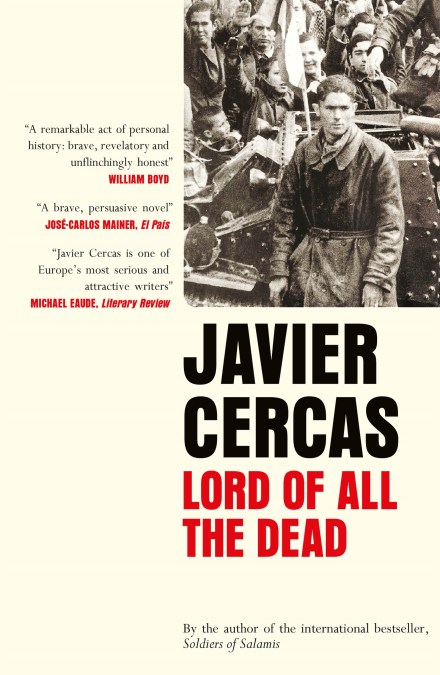

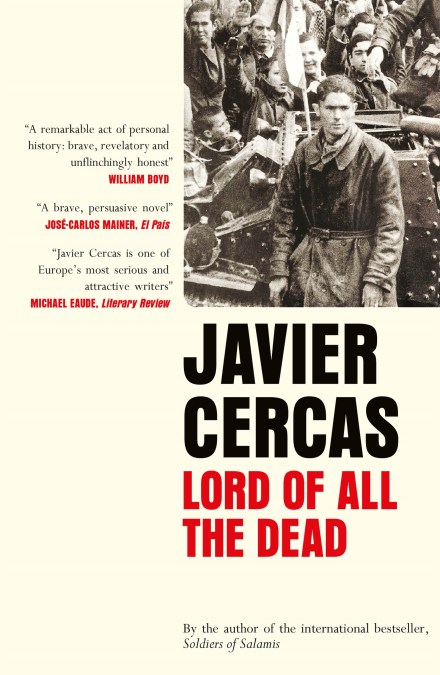

The Tenant and The Motive by Javier Cercas (completed 1/6/11)

The Tenant and The Motive are two light yet darkly humorous novellas by one of Spain's leading contemporary authors, who is best known for his novel Soldiers of Salamis, the winner of the 2004 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. In the first novella, a university professor of linguistics experiences a Kafkaesque turn of events after an ankle sprain, as a renowned (but unknown to him) fellow linguistics professor moves in next door to him, takes over his office and classes, and steals his girlfriend while he remains powerless to change his fate. In The Motive, a part-time lawyer and budding writer envisions a novel in which a young couple in financial straits murders an elderly man for his hidden money, but he has trouble putting voices to the characters. The writer befriends a couple and an old man who live in the same building as he, and, in a reversal of the concept of "life becomes art", he injects himself and alters their three lives, using taped conversations to write his story. These novellas were a joy to read, and I'll be looking for more of Cercas' works in the near future.

The Tenant and The Motive are two light yet darkly humorous novellas by one of Spain's leading contemporary authors, who is best known for his novel Soldiers of Salamis, the winner of the 2004 Independent Foreign Fiction Prize. In the first novella, a university professor of linguistics experiences a Kafkaesque turn of events after an ankle sprain, as a renowned (but unknown to him) fellow linguistics professor moves in next door to him, takes over his office and classes, and steals his girlfriend while he remains powerless to change his fate. In The Motive, a part-time lawyer and budding writer envisions a novel in which a young couple in financial straits murders an elderly man for his hidden money, but he has trouble putting voices to the characters. The writer befriends a couple and an old man who live in the same building as he, and, in a reversal of the concept of "life becomes art", he injects himself and alters their three lives, using taped conversations to write his story. These novellas were a joy to read, and I'll be looking for more of Cercas' works in the near future.

6kidzdoc

The Gospel According to Jesus Christ by José Saramago (Portugal, completed 1/4/11)

In this captivating and intriguing novel, Saramago portrays Christ as an Everyman, an imperfect but deeply sensitive man plagued by doubt, insecurity, and passionate feelings toward and opinions about others, particularly Joseph and Mary Magdalene. It begins with the story of Joseph, a loving husband and good provider, and his young wife Mary, in the days leading up to Jesus' birth in a cave at the edge of Bethlehem. Soon afterward, Joseph overhears a group of soldiers discussing King Herod's premonition about the recent birth of the future King of the Jews, and his plan to kill all male children under three years of age. Joseph chooses to flee with his wife and young son, and his failure to warn the villagers of the plan results in the Massacre of the Innocents, an event that will plague Joseph the rest of his life and have a great impact upon the young Jesus after his father's death.

After Jesus learns of his death he undertakes a journey to escape his father's crime and to determine what his legacy is meant to be. He falls under the wing of a mysterious Shepherd, who seemingly knows a lot about Christ's past and future without being a Jew or a man of God. Jesus later encounters God in the desert, and there he learns about God's plan for him.

The most surprising and controversial aspects of the novel follow, as Christ engages in a relationship with Mary Magdalene after she treats and dresses his infected foot, and becomes conflicted with God's plan to instill Christianity throughout the world, which will result in the death and suffering of millions of believers and opponents.

The Gospel According to Jesus Christ left me stunned and agape at several points, and I can certainly understand why it engendered such strong opposition, particularly by the Roman Catholic Church. However, I'm glad I read it, and I found it to be most enjoyable and unforgettable.

In this captivating and intriguing novel, Saramago portrays Christ as an Everyman, an imperfect but deeply sensitive man plagued by doubt, insecurity, and passionate feelings toward and opinions about others, particularly Joseph and Mary Magdalene. It begins with the story of Joseph, a loving husband and good provider, and his young wife Mary, in the days leading up to Jesus' birth in a cave at the edge of Bethlehem. Soon afterward, Joseph overhears a group of soldiers discussing King Herod's premonition about the recent birth of the future King of the Jews, and his plan to kill all male children under three years of age. Joseph chooses to flee with his wife and young son, and his failure to warn the villagers of the plan results in the Massacre of the Innocents, an event that will plague Joseph the rest of his life and have a great impact upon the young Jesus after his father's death.

After Jesus learns of his death he undertakes a journey to escape his father's crime and to determine what his legacy is meant to be. He falls under the wing of a mysterious Shepherd, who seemingly knows a lot about Christ's past and future without being a Jew or a man of God. Jesus later encounters God in the desert, and there he learns about God's plan for him.

The most surprising and controversial aspects of the novel follow, as Christ engages in a relationship with Mary Magdalene after she treats and dresses his infected foot, and becomes conflicted with God's plan to instill Christianity throughout the world, which will result in the death and suffering of millions of believers and opponents.

The Gospel According to Jesus Christ left me stunned and agape at several points, and I can certainly understand why it engendered such strong opposition, particularly by the Roman Catholic Church. However, I'm glad I read it, and I found it to be most enjoyable and unforgettable.

7rebeccanyc

The Maias by José Maria Eça de Queirós, Portugal, originally published 1888, translation 2007

The Maia family is old and rich, but by the 1880s has shruk down to a grandfather and grandson. Trained as a doctor, the grandson Carlos (whose parents, both dead, had a tragic romance) lackadaisically sets up a Lisbon practice, but mostly spends time hanging out with friends of various sorts and having casual affairs with married women. before setting off a complicated chain of events by falling in love with one particular woman.

The novel, considered Eça de Queirós's masterpiece, paints a broad, often satiric portrait of the Portuguese upper classes, their prejudices, the world they lived in, their political and artistic controversies, and their place in the larger European context. While I found this insight into a world long gone (and deservedly so) fascinating, I became irritated by Carlos and his superficiality by the end of this lengthy book, and found the coincidence on which the plot turns a little contrived and melodramatic. Nonetheless, the characterizations are wonderful; all kinds of people, at least people of the nonworking classes, spring to life in Eça de Queirós's writing.

The Maia family is old and rich, but by the 1880s has shruk down to a grandfather and grandson. Trained as a doctor, the grandson Carlos (whose parents, both dead, had a tragic romance) lackadaisically sets up a Lisbon practice, but mostly spends time hanging out with friends of various sorts and having casual affairs with married women. before setting off a complicated chain of events by falling in love with one particular woman.

The novel, considered Eça de Queirós's masterpiece, paints a broad, often satiric portrait of the Portuguese upper classes, their prejudices, the world they lived in, their political and artistic controversies, and their place in the larger European context. While I found this insight into a world long gone (and deservedly so) fascinating, I became irritated by Carlos and his superficiality by the end of this lengthy book, and found the coincidence on which the plot turns a little contrived and melodramatic. Nonetheless, the characterizations are wonderful; all kinds of people, at least people of the nonworking classes, spring to life in Eça de Queirós's writing.

8avaland

>7 rebeccanyc: Just reading through the thread...wow, you didn't waste anytime snapping that one up:-)

9rebeccanyc

Well, I ordered it right away and then I had a long round-trip plane trip that seemed designed for a long, readable book!

10msjohns615

2, 7: I've been wanting to try Eça de Queiróz for a while; I read an interview with Borges once where he talked about how much his mother and he liked to read Queiróz when he was a kid. Maybe I'll stop by the Portuguese fiction section of the library tomorrow!

11msjohns615

SPAIN

Cantar de Mio Cid--Anonymous

This epic story of Spain's national hero, Rodrigo Ruy Díaz, a.k.a. El Cid, was a great deal of fun to read. The language is very colorful and I enjoyed trying to imitate the medieval Spanish language of El Cid and his compatriots. I was surprised by how realistic it was, and enjoyed the emphasis placed on calm, measured restraint over quick-tempered, violent reactions.

Cantar de Mio Cid--Anonymous

This epic story of Spain's national hero, Rodrigo Ruy Díaz, a.k.a. El Cid, was a great deal of fun to read. The language is very colorful and I enjoyed trying to imitate the medieval Spanish language of El Cid and his compatriots. I was surprised by how realistic it was, and enjoyed the emphasis placed on calm, measured restraint over quick-tempered, violent reactions.

12janemarieprice

PORTUGAL

Blindness by Jose Saramago

“It was my fault, she sobbed, and it was true, no one could deny it, but it is also true, if this brings her any consolation, that if, before every action, we were to begin by weighing up the consequences, thinking about them in earnest, first the immediate consequences, then the probably, then the possible, then the imaginable ones, we should never move beyond the point where our first thought brought us to a halt. The good and evil resulting from our words and deeds go on apportioning themselves, one assumes in a reasonably uniform and balanced way, throughout all the days to follow, including those endless days, when we shall not be here to find out, to congratulate ourselves or ask for pardon, indeed there are those who claim that this is the much-talked-of immortality, Possibly, but this man is dead and must be buried.”

The above passage is representative of the entire book – both the style, large chunks with no quotation marks with commas usually separating the dialog, and themes, philosophical discussions from an oft-present though unidentified narrator mixed with stark realities of a world in which a contagious white blindness strikes a country. In the dystopian society which develops, a large group is quarantined in an abandoned mental hospital. The characters remain unnamed as does the location. We follow them through gruesome trials and menial tasks. Saramago is a beautiful writer, though I don’t think for everyone. The pace is slow; the narrator frequently interjects pieces of plot information, past or future events, or simply musings. Another example:

“In fact, however reluctant we might be to admit it, these distasteful realities of life also have to be considered, when the bowels function normally, anyone can have ideas, debate, for example, whether there exists a direct relationship between the eyes and feelings, or whether the sense of responsibility is the natural consequence of clear vision, but when we are in great distress and plagued by pain and anguish that is when the animal side of our nature becomes most apparent.”

I enjoyed this very much, and I think it will stay with me for quite some time. Not a comfortable read but a very good one.

Blindness by Jose Saramago

“It was my fault, she sobbed, and it was true, no one could deny it, but it is also true, if this brings her any consolation, that if, before every action, we were to begin by weighing up the consequences, thinking about them in earnest, first the immediate consequences, then the probably, then the possible, then the imaginable ones, we should never move beyond the point where our first thought brought us to a halt. The good and evil resulting from our words and deeds go on apportioning themselves, one assumes in a reasonably uniform and balanced way, throughout all the days to follow, including those endless days, when we shall not be here to find out, to congratulate ourselves or ask for pardon, indeed there are those who claim that this is the much-talked-of immortality, Possibly, but this man is dead and must be buried.”

The above passage is representative of the entire book – both the style, large chunks with no quotation marks with commas usually separating the dialog, and themes, philosophical discussions from an oft-present though unidentified narrator mixed with stark realities of a world in which a contagious white blindness strikes a country. In the dystopian society which develops, a large group is quarantined in an abandoned mental hospital. The characters remain unnamed as does the location. We follow them through gruesome trials and menial tasks. Saramago is a beautiful writer, though I don’t think for everyone. The pace is slow; the narrator frequently interjects pieces of plot information, past or future events, or simply musings. Another example:

“In fact, however reluctant we might be to admit it, these distasteful realities of life also have to be considered, when the bowels function normally, anyone can have ideas, debate, for example, whether there exists a direct relationship between the eyes and feelings, or whether the sense of responsibility is the natural consequence of clear vision, but when we are in great distress and plagued by pain and anguish that is when the animal side of our nature becomes most apparent.”

I enjoyed this very much, and I think it will stay with me for quite some time. Not a comfortable read but a very good one.

13msjohns615

12: I've always liked that book a lot, and I've given away a few copies of it to friends. It's a fantastic premise for a story about human morality in difficult situations. The movie, though, was not so great.

14msjohns615

SPAIN

Libro de buen amor (The Book of Good Love)--Juan Ruiz (Archipreste de Hita)

I'm not sure if many people in this group are interested in older (medieval) literature from around the world, but I wanted to mention two really great books written in medieval Spain. I've heard a lot of people compare The Book of Good Love to two other books of that time: Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and Bocaccio's Decameron. I think anyone who enjoys either of those two books would certainly be interested in Juan Ruiz's masterpiece, which is full of fables, parables and exempla, as well as great debates between the author and Don Amor and Doña Venus, and an epic showdown between Don Carnal and Doña Cuaresma. There's also a lot of romantic intrigue, as the author's procuress Trotaconventos tries to convince a series of ladies to acquiesce to the desires of her client.

I found this book particularly interesting because of its use of various levels of ambiguity in delivering its message on how to practice "good love." It requires an active reader who is able to make his or her own decisions about how to interpret the text. the Archipreste makes this clear from the beginning: those of us who want to find examples of good love will find them here, but those who wish to learn of the practice of another sort of love will also learn much from his book. It's rather subversive, really, and quite remarkable for a book whose two editions were written in 1330 and 1343.

There is an edition available on Amazon of a translation by Elisha Kent Kane which is, at least according to the user comments, a good one. I also found this copy of an advertisement from the original 1933 publication of this English translation:

The Book of Good Love translated into English Verse

The statement in that advertisement about Juan Ruiz writing this book while in prison is probably not true; it is highly likely that the prison he mentions is a metaphorical one...

Libro de buen amor (The Book of Good Love)--Juan Ruiz (Archipreste de Hita)

I'm not sure if many people in this group are interested in older (medieval) literature from around the world, but I wanted to mention two really great books written in medieval Spain. I've heard a lot of people compare The Book of Good Love to two other books of that time: Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and Bocaccio's Decameron. I think anyone who enjoys either of those two books would certainly be interested in Juan Ruiz's masterpiece, which is full of fables, parables and exempla, as well as great debates between the author and Don Amor and Doña Venus, and an epic showdown between Don Carnal and Doña Cuaresma. There's also a lot of romantic intrigue, as the author's procuress Trotaconventos tries to convince a series of ladies to acquiesce to the desires of her client.

I found this book particularly interesting because of its use of various levels of ambiguity in delivering its message on how to practice "good love." It requires an active reader who is able to make his or her own decisions about how to interpret the text. the Archipreste makes this clear from the beginning: those of us who want to find examples of good love will find them here, but those who wish to learn of the practice of another sort of love will also learn much from his book. It's rather subversive, really, and quite remarkable for a book whose two editions were written in 1330 and 1343.

There is an edition available on Amazon of a translation by Elisha Kent Kane which is, at least according to the user comments, a good one. I also found this copy of an advertisement from the original 1933 publication of this English translation:

The Book of Good Love translated into English Verse

The statement in that advertisement about Juan Ruiz writing this book while in prison is probably not true; it is highly likely that the prison he mentions is a metaphorical one...

15msjohns615

SPAIN

La Celestina--Fernando de Rojas

This novel in dialogue was written right around 1500, and is an interesting bridge between medieval and Renaissance texts. It's a lot of fun too: the language is quite vulgar and the subject matter is pretty racy. Lots of sex, violence, witchcraft and prostitution. The tragic story of the romance between Calisto and Melibea, who are brought together with the help of the aging procuress Celestina, had a great deal of influence on the picaresque novels of the late-16th and early-17th centuries. I've been a fan of this book for a while, and was very pleased when I re-read it recently.

I've been reading medieval books because I wanted to get a better idea of Spanish literary traditions leading up to the turn of the 17th century, when Cervantes wrote Don Quijote. This book is especially compelling to a fan of Don Quijote because it depicts the trials and tribulations of Calisto, a chivalrous lover, when his idealized behavior clashes with the reality of the world that surrounds him; of course, a similar thing happens to Don Quijote when he roams Spain acting in accordance with the codes of chivalrous behavior established in books like Orlando furioso and Amadís de Gaula.

The Amazon.com web page for the English translation has some rather exuberant quotes about this book:

"A vibrantly alive work of art...It is no exaggeration to equate the artistic originality and conquests of Rojas with the achievements of Cervantes, Velazquez, or Goya."

-Juan Goytisolo, from the Introduction

"Without Celestina, the great tradition of the novel in Spanish would not exist: the works of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Carlos Fuentes, and Juan Goytisolo all descend from Mother Celestina. In his brilliant translation, Peter Bush makes this classic of potions and passions into a delightfully intoxicating, uniquely Spanish treat for contemporary readers."

-Julio Ortega, Brown University

Anyway, it's certainly one of my favorite books!

La Celestina--Fernando de Rojas

This novel in dialogue was written right around 1500, and is an interesting bridge between medieval and Renaissance texts. It's a lot of fun too: the language is quite vulgar and the subject matter is pretty racy. Lots of sex, violence, witchcraft and prostitution. The tragic story of the romance between Calisto and Melibea, who are brought together with the help of the aging procuress Celestina, had a great deal of influence on the picaresque novels of the late-16th and early-17th centuries. I've been a fan of this book for a while, and was very pleased when I re-read it recently.

I've been reading medieval books because I wanted to get a better idea of Spanish literary traditions leading up to the turn of the 17th century, when Cervantes wrote Don Quijote. This book is especially compelling to a fan of Don Quijote because it depicts the trials and tribulations of Calisto, a chivalrous lover, when his idealized behavior clashes with the reality of the world that surrounds him; of course, a similar thing happens to Don Quijote when he roams Spain acting in accordance with the codes of chivalrous behavior established in books like Orlando furioso and Amadís de Gaula.

The Amazon.com web page for the English translation has some rather exuberant quotes about this book:

"A vibrantly alive work of art...It is no exaggeration to equate the artistic originality and conquests of Rojas with the achievements of Cervantes, Velazquez, or Goya."

-Juan Goytisolo, from the Introduction

"Without Celestina, the great tradition of the novel in Spanish would not exist: the works of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Carlos Fuentes, and Juan Goytisolo all descend from Mother Celestina. In his brilliant translation, Peter Bush makes this classic of potions and passions into a delightfully intoxicating, uniquely Spanish treat for contemporary readers."

-Julio Ortega, Brown University

Anyway, it's certainly one of my favorite books!

16rebeccanyc

Portugal The History of the Siege of Lisbon by José Saramago (originally published 1989, English translation 1996)

I am grateful to the Author Theme Reads group for making Saramago the mini-author for January-April; otherwise I would not have read this wonderful book. Saramago interweaves the story of a 20th century Lisbon proofreader, an isolated, serious, professionally responsible man, who unexpectedly inserts a "not" into a history of the siege of Lisbon, indicating that the Crusaders did not come to the aid of of the Christian Portuguese laying siege to the Moor-held city of Lisbon, with an alternative history of that 12th century siege told through the eyes of the participants, and with a love story. He is not only a wonderful story-teller, but an amazing writer with a magical way with language, almost piling words on to bring out very slightly different shades of meaning, finding the telling detail to illuminate character and place, exploring multiple facets of both contemporary and medieval life, and implicitly drawing parallels between them.

Through this story, Saramago plays with the meaning of history and the writing of history, the role of individuals, the centrality of daily life, the use and abuse of language, the grittiness of war, and the transformative power of love. His writing style is sometimes difficult to follow, requiring and rewarding careful attention, but is beautiful (and, I must assume, beautifully translated). I have to believe Saramago had fun writing this delightful book. This was my first Saramago, but it will not be my last.

I am grateful to the Author Theme Reads group for making Saramago the mini-author for January-April; otherwise I would not have read this wonderful book. Saramago interweaves the story of a 20th century Lisbon proofreader, an isolated, serious, professionally responsible man, who unexpectedly inserts a "not" into a history of the siege of Lisbon, indicating that the Crusaders did not come to the aid of of the Christian Portuguese laying siege to the Moor-held city of Lisbon, with an alternative history of that 12th century siege told through the eyes of the participants, and with a love story. He is not only a wonderful story-teller, but an amazing writer with a magical way with language, almost piling words on to bring out very slightly different shades of meaning, finding the telling detail to illuminate character and place, exploring multiple facets of both contemporary and medieval life, and implicitly drawing parallels between them.

Through this story, Saramago plays with the meaning of history and the writing of history, the role of individuals, the centrality of daily life, the use and abuse of language, the grittiness of war, and the transformative power of love. His writing style is sometimes difficult to follow, requiring and rewarding careful attention, but is beautiful (and, I must assume, beautifully translated). I have to believe Saramago had fun writing this delightful book. This was my first Saramago, but it will not be my last.

17janemarieprice

PORTUGAL

Seeing by Jose Saramago

I loved Blindness and so was looking forward to this semi-sequel. Unfortunately it was a disappointment. The language is just as beautiful:

"The second voter took another ten minutes to appear, but from then on, albeit unenthusiastically, one by one, like autumn leaves slowly detaching themselves from the boughs of a tree, the ballot papers dropped into the ballot box."

And the premise is intriguing – that of an election where the majority of people submit blank ballots in the capital city, the government abandons the place, and political maneuverings follow in which the characters of Blindness become suspects. Somehow, though, it just didn’t hold my interest in the same way. I found the pacing extremely slow and kept setting it down for long periods.

I find the narration of both books fascinating. Sometimes it interjects as in this excerpt:

"or if it simply had to happen because that was its destiny, from which would spring soon-to-be-revealed consequences, forcing the narrator to set aside the story he was intending to write and to follow the new course that had suddenly appeared on his navigation chart. It is difficult to give such an either-or question an answer likely to satisfy such a reader totally. Unless, of course, the narrator wwere to be unusually frank and confess that he had never been quite sure how to bring to a successful conclusion this extraordinary tale of a city which, en masse, decided to return blank ballot papers"

Another interesting bit is the unnamed characters. everyone is referred to in some way in which they are known – their job, something that happened to them etc. – except the dog which does have a name. Curious.

Seeing by Jose Saramago

I loved Blindness and so was looking forward to this semi-sequel. Unfortunately it was a disappointment. The language is just as beautiful:

"The second voter took another ten minutes to appear, but from then on, albeit unenthusiastically, one by one, like autumn leaves slowly detaching themselves from the boughs of a tree, the ballot papers dropped into the ballot box."

And the premise is intriguing – that of an election where the majority of people submit blank ballots in the capital city, the government abandons the place, and political maneuverings follow in which the characters of Blindness become suspects. Somehow, though, it just didn’t hold my interest in the same way. I found the pacing extremely slow and kept setting it down for long periods.

I find the narration of both books fascinating. Sometimes it interjects as in this excerpt:

"or if it simply had to happen because that was its destiny, from which would spring soon-to-be-revealed consequences, forcing the narrator to set aside the story he was intending to write and to follow the new course that had suddenly appeared on his navigation chart. It is difficult to give such an either-or question an answer likely to satisfy such a reader totally. Unless, of course, the narrator wwere to be unusually frank and confess that he had never been quite sure how to bring to a successful conclusion this extraordinary tale of a city which, en masse, decided to return blank ballot papers"

Another interesting bit is the unnamed characters. everyone is referred to in some way in which they are known – their job, something that happened to them etc. – except the dog which does have a name. Curious.

18Rise

PORTUGAL

Manual of Painting and Calligraphy by José Saramago, translated by Giovanni Pontiero

The novel is narrated by H., a fifty-year old painter commissioned by S. for a portrait. The first few pages unfold slowly, telling of H.'s difficulties in producing two simultaneous portraits of his client. In order to get around to this problem, or more like to escape from it, H. decided to produce another third portrait of S., but this time the image will be in words. Through sudden impulse or instinct, H. decided to turn into writing (the "calligraphy" in the title).

I shall go on painting the second picture but I know it will never be finished. I have tried without success and there is no clearer proof of my failure and frustration than this sheet of paper on which I am starting to write. Sooner or later I shall move from the first picture to the second and then turn to my writing, or I shall skip the intermediate stage or stop in the middle of a word to apply another brushstroke to the portrait commissioned by S. or to that other portrait alongside it which S. will never see. When that day comes I shall know no more than I know today (namely, that both pictures are worthless). But I shall be able to decide whether I was right to allow myself to be tempted by a form of expression which is not mine, although this same temptation may mean in the end that the form of expression I have been using as carefully as if I were following the fixed rules of some manual was not mine either. For the moment I prefer not to think about what I shall do if this writing comes to nothing, if, from now on, my white canvases and blank sheets of paper become a world orbiting thousands of light-years away where I shall not be able to leave the slightest trace. If, in a word, it were dishonest to pick up a brush or pen or if, once more in a word (the first time I did not succeed), I must deny myself the right to communicate or express myself, because I shall have tried and failed and there will be no further opportunities.

The opening paragraph of a José Saramago is unmistakable in its trademark tone. The lulls and pauses in the phrasing are searching for a way forward. The prose is laden with hesitations and qualifications, trying to overcome the clauses that skirt away from the general idea. The ideas are spreading like ripples in the pond, emanating from the center of consciousness. Above the surface hovers a unique voice, a singular mind, a ruthless thought process. Below is raging calm, propagating through perfect control of rhythm. The only comparison I can immediately think of is the artful opening of a Javier Marías.

I never expected this book to develop right off the bat a similar theme of another novel I finished last year, also from the Portuguese. The Stream of Life by Clarice Lispector (translated by Elizabeth Lowe and Earl Fitz) is narrated by a female painter who writes of her innermost consciousness and feelings the way colors unravel from the strokes of her paint brush, the way consciousness streams forth from a fountain of imagination. But where Lispector's prose issues forth quick as silver, Saramago's brush paints from a slow easel, building from primary colors as he established his plot. As in Lispector's "art book," plot is probably the least of Saramago's concern here. Manual is, from the outset, a novel of ideas: ideas about art, about the expressions and forms that art makes, and the relationships of these art forms.

Manual de Pintura e Caligrafia first came out in 1976, only Saramago's second published novel at that time. The first novel, still untranslated, appeared almost thirty years earlier. In between the two, he produced three collections of poetry (he did not publish poetry since then) and four collections of newspaper articles. The English translation of Manual appeared in hardcover from Carcanet Press in 1994, and in paperback from the same publisher a year later. The translation, however, has since gone out of print.

Among his earliest works in the original Portuguese, this novel is the first "window" to his works, not only because it remains to be the earliest with an English translation, but because it anticipates Saramago's mature themes, images, and preoccupations - names, blindness, political engagement, religion, love story. Last year The Collected Novels of José Saramago was released in e-book format, as an exclusive compendium of Saramago's fiction (twelve novels and one novella). This collection is missing Manual of Painting and Calligraphy.

Manual of Painting and Calligraphy by José Saramago, translated by Giovanni Pontiero

The novel is narrated by H., a fifty-year old painter commissioned by S. for a portrait. The first few pages unfold slowly, telling of H.'s difficulties in producing two simultaneous portraits of his client. In order to get around to this problem, or more like to escape from it, H. decided to produce another third portrait of S., but this time the image will be in words. Through sudden impulse or instinct, H. decided to turn into writing (the "calligraphy" in the title).

I shall go on painting the second picture but I know it will never be finished. I have tried without success and there is no clearer proof of my failure and frustration than this sheet of paper on which I am starting to write. Sooner or later I shall move from the first picture to the second and then turn to my writing, or I shall skip the intermediate stage or stop in the middle of a word to apply another brushstroke to the portrait commissioned by S. or to that other portrait alongside it which S. will never see. When that day comes I shall know no more than I know today (namely, that both pictures are worthless). But I shall be able to decide whether I was right to allow myself to be tempted by a form of expression which is not mine, although this same temptation may mean in the end that the form of expression I have been using as carefully as if I were following the fixed rules of some manual was not mine either. For the moment I prefer not to think about what I shall do if this writing comes to nothing, if, from now on, my white canvases and blank sheets of paper become a world orbiting thousands of light-years away where I shall not be able to leave the slightest trace. If, in a word, it were dishonest to pick up a brush or pen or if, once more in a word (the first time I did not succeed), I must deny myself the right to communicate or express myself, because I shall have tried and failed and there will be no further opportunities.

The opening paragraph of a José Saramago is unmistakable in its trademark tone. The lulls and pauses in the phrasing are searching for a way forward. The prose is laden with hesitations and qualifications, trying to overcome the clauses that skirt away from the general idea. The ideas are spreading like ripples in the pond, emanating from the center of consciousness. Above the surface hovers a unique voice, a singular mind, a ruthless thought process. Below is raging calm, propagating through perfect control of rhythm. The only comparison I can immediately think of is the artful opening of a Javier Marías.

I never expected this book to develop right off the bat a similar theme of another novel I finished last year, also from the Portuguese. The Stream of Life by Clarice Lispector (translated by Elizabeth Lowe and Earl Fitz) is narrated by a female painter who writes of her innermost consciousness and feelings the way colors unravel from the strokes of her paint brush, the way consciousness streams forth from a fountain of imagination. But where Lispector's prose issues forth quick as silver, Saramago's brush paints from a slow easel, building from primary colors as he established his plot. As in Lispector's "art book," plot is probably the least of Saramago's concern here. Manual is, from the outset, a novel of ideas: ideas about art, about the expressions and forms that art makes, and the relationships of these art forms.

Manual de Pintura e Caligrafia first came out in 1976, only Saramago's second published novel at that time. The first novel, still untranslated, appeared almost thirty years earlier. In between the two, he produced three collections of poetry (he did not publish poetry since then) and four collections of newspaper articles. The English translation of Manual appeared in hardcover from Carcanet Press in 1994, and in paperback from the same publisher a year later. The translation, however, has since gone out of print.

Among his earliest works in the original Portuguese, this novel is the first "window" to his works, not only because it remains to be the earliest with an English translation, but because it anticipates Saramago's mature themes, images, and preoccupations - names, blindness, political engagement, religion, love story. Last year The Collected Novels of José Saramago was released in e-book format, as an exclusive compendium of Saramago's fiction (twelve novels and one novella). This collection is missing Manual of Painting and Calligraphy.

19berthirsch

Spain-a book i received as a reviewer for LT:

The Anatomy of a Moment: Thirty-Five Minutes in History and Imagination… by Javier Cercas

This review was written for LibraryThing Early Reviewers.

The Anatomy of a Moment by Javier Cercas

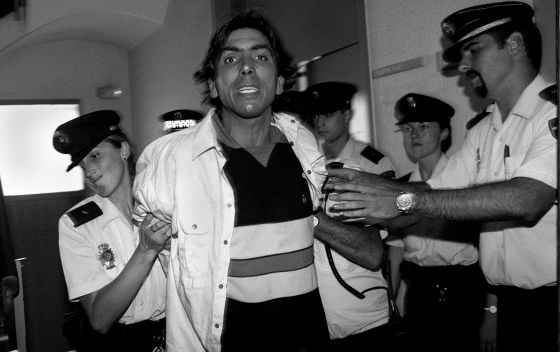

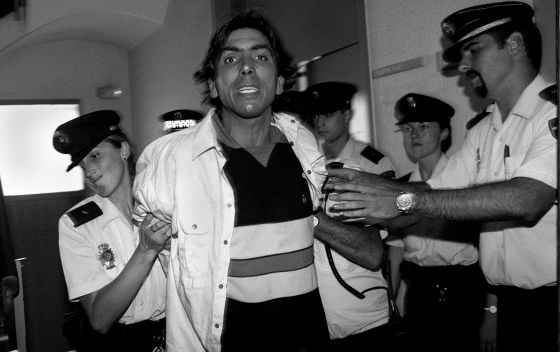

A history, a meta-non-fiction, written by the acclaimed Spanish novelist Javier Cercas. An Anatomy of a Moment takes place on 23February at the Parliament building (Cortes) in Madrid, Spain. Throughout the end of 1980 the new Spanish democracy designed and assembled through the leadership of the former Francoist Alfonso Suarez has begun to unravel. In the prior two centuries of Spanish history a coup d’état, or as the Spanish call it: a golpe de estado, had occurred over 50 times. The last, in 1936, had brought Franco into power. The new democracy began in 1976 at King Juan Carlos’s request following Franco’s death, but by 1980 Suarez had lost the support of all his constituents: the King, the church, the military, the leftists, the bankers and businessmen. Picked by the King as an “errand boy” to serve as a transitional figure Suarez had outlived his usefulness.

This book focuses on several of the leading characters and protagonists at the center of this moment: Prime Minister Alfonso Suarez, the Communist party leader Santiago Carillo, the Deputy prime Minister General Gutierrez Mellado, Lt. Colonel Tejero who entered the Cortes pistol in hand like his predecessor General Pavia who entered on horseback in 1874, the military boss behind the plot and the former Secretary to the king, General Alfonso Armado and many of his fellow golpistas. Cercas deftly provides background information on all and describes the intermingled web of relationships that connect them all to this moment in the Spanish Republic’s history.

Referring to the famous photo of Tejero with three pointed hat and pistol in hand he effectively builds a panoramic shot inclusive of the various politicians cowering under their desks, the courageous Suarez defiantly smoking a cigarette as he sits erect behind his desk and on the other side of the Cortes Carillo too defiantly refusing to cower in fear.

Cercas draws on historic contexts as he writes that “history repeats itself. Marx observed that great events and characters appear in history twice, first as tragedy and then as farce, just as in moments of profound transformation men, frightened by their responsibility, invoked the spirits of the past, adopted their names, their mannerisms and slogans to represent with the prestigious disguise and detachable language a new historical scene as if it were a séance.”

As an American (USA) reader much of the nuances of Spanish history are unfamiliar yet enough is explained that (with an occasional assist form Wikipedia) I was able to gain a deeper insight into Spain’s recent history of its republic. Much of Franco and the Falangist past is a part of this history and the Republics survival is in response to this.

In This intriguing re-imagination of his country's history Javier Cercas has thrown down the gauntlet bidding other great novelists do likewise with their own national histories. I began to wonder how several of our current novelists could approach our recent events: the Clinton years, the Reagan years, both Bushes and the historic Obama; all could be imagined and understood on a deeper level if mined by a novelists touch. Several moments in our own history come to mind: the Oliver North hearings, Colin Powell’s presentation to the UN Security Council, Clinton’s “I did not have sex with that woman”, LBJ taking the oath of office aboard Air Force One as it made its way back to DC form Dallas: all these moments are seared in photographic memory waiting to be dramatized. If Cercas was from the United States he might be busy at this very moment writing his next book.

The Anatomy of a Moment: Thirty-Five Minutes in History and Imagination… by Javier Cercas

This review was written for LibraryThing Early Reviewers.

The Anatomy of a Moment by Javier Cercas

A history, a meta-non-fiction, written by the acclaimed Spanish novelist Javier Cercas. An Anatomy of a Moment takes place on 23February at the Parliament building (Cortes) in Madrid, Spain. Throughout the end of 1980 the new Spanish democracy designed and assembled through the leadership of the former Francoist Alfonso Suarez has begun to unravel. In the prior two centuries of Spanish history a coup d’état, or as the Spanish call it: a golpe de estado, had occurred over 50 times. The last, in 1936, had brought Franco into power. The new democracy began in 1976 at King Juan Carlos’s request following Franco’s death, but by 1980 Suarez had lost the support of all his constituents: the King, the church, the military, the leftists, the bankers and businessmen. Picked by the King as an “errand boy” to serve as a transitional figure Suarez had outlived his usefulness.

This book focuses on several of the leading characters and protagonists at the center of this moment: Prime Minister Alfonso Suarez, the Communist party leader Santiago Carillo, the Deputy prime Minister General Gutierrez Mellado, Lt. Colonel Tejero who entered the Cortes pistol in hand like his predecessor General Pavia who entered on horseback in 1874, the military boss behind the plot and the former Secretary to the king, General Alfonso Armado and many of his fellow golpistas. Cercas deftly provides background information on all and describes the intermingled web of relationships that connect them all to this moment in the Spanish Republic’s history.

Referring to the famous photo of Tejero with three pointed hat and pistol in hand he effectively builds a panoramic shot inclusive of the various politicians cowering under their desks, the courageous Suarez defiantly smoking a cigarette as he sits erect behind his desk and on the other side of the Cortes Carillo too defiantly refusing to cower in fear.

Cercas draws on historic contexts as he writes that “history repeats itself. Marx observed that great events and characters appear in history twice, first as tragedy and then as farce, just as in moments of profound transformation men, frightened by their responsibility, invoked the spirits of the past, adopted their names, their mannerisms and slogans to represent with the prestigious disguise and detachable language a new historical scene as if it were a séance.”

As an American (USA) reader much of the nuances of Spanish history are unfamiliar yet enough is explained that (with an occasional assist form Wikipedia) I was able to gain a deeper insight into Spain’s recent history of its republic. Much of Franco and the Falangist past is a part of this history and the Republics survival is in response to this.

In This intriguing re-imagination of his country's history Javier Cercas has thrown down the gauntlet bidding other great novelists do likewise with their own national histories. I began to wonder how several of our current novelists could approach our recent events: the Clinton years, the Reagan years, both Bushes and the historic Obama; all could be imagined and understood on a deeper level if mined by a novelists touch. Several moments in our own history come to mind: the Oliver North hearings, Colin Powell’s presentation to the UN Security Council, Clinton’s “I did not have sex with that woman”, LBJ taking the oath of office aboard Air Force One as it made its way back to DC form Dallas: all these moments are seared in photographic memory waiting to be dramatized. If Cercas was from the United States he might be busy at this very moment writing his next book.

20Trifolia

Spain: Het geheim van de Hoffmans (El secreto de los Hoffman) by Alejandro Palomas - 4 stars

When the ex-husband, the daughter and the two grand-children meet for the funeral of the grand-mother, a family-secret hangs between them like fog. The death of the two parents of the grand-children over 20 years ago not only has caused a rift in the family but also had a deep personal impact on every individual involved. In the days that follow the funeral, the family learns to deal with their past and tries to find a new balance.

This is a gem of a book, not so much because of the story - 200 pages is far too little to go into each person's character in depth - but because of the beautiful style and poetic language, the subtlety of the phrasing, the delicacy of the words. Reading this book is like watching a family-portrait where the people come to life while you're watching. Recommended, but - as often - not yet available in English yet, I'm afraid.

When the ex-husband, the daughter and the two grand-children meet for the funeral of the grand-mother, a family-secret hangs between them like fog. The death of the two parents of the grand-children over 20 years ago not only has caused a rift in the family but also had a deep personal impact on every individual involved. In the days that follow the funeral, the family learns to deal with their past and tries to find a new balance.

This is a gem of a book, not so much because of the story - 200 pages is far too little to go into each person's character in depth - but because of the beautiful style and poetic language, the subtlety of the phrasing, the delicacy of the words. Reading this book is like watching a family-portrait where the people come to life while you're watching. Recommended, but - as often - not yet available in English yet, I'm afraid.

21Trifolia

Portugal: Act of the Damned by António Lobo Antunes - 4 stars

A whirlwind of a book about a Portuguese family in the 1970's, gathering together by the death-bed of the patriarch of the family, when their own world of wealth as they knew it is falling apart. With a vivid street-party in the background, the family's own disasters are taking place. The strength and beauty of this book especially lies in the extraordinary way in which Antunes writes. E.g. when one person thinks, you follow his of her way of thinking to the extreme, with thoughts tumbling, falling over one another in turmoil and chaos. The storyline is not as important although it's biting and sarcastic as to emphasize the tone.

This was not an easy read but very rewarding in the end. If you like Garcia Marquez, you might give this one a try. It certainly is very different from anything I've read lately (and ever)...

A whirlwind of a book about a Portuguese family in the 1970's, gathering together by the death-bed of the patriarch of the family, when their own world of wealth as they knew it is falling apart. With a vivid street-party in the background, the family's own disasters are taking place. The strength and beauty of this book especially lies in the extraordinary way in which Antunes writes. E.g. when one person thinks, you follow his of her way of thinking to the extreme, with thoughts tumbling, falling over one another in turmoil and chaos. The storyline is not as important although it's biting and sarcastic as to emphasize the tone.

This was not an easy read but very rewarding in the end. If you like Garcia Marquez, you might give this one a try. It certainly is very different from anything I've read lately (and ever)...

22cammykitty

The House of Ulloa is a late 19th century classic from Spain, written by a woman too!!! This novel was many things, and a certainly don't know how to give you a synopsis. A naive priest (yes, many a Latino story starts with a naive priest) is sent to work as the chaplain for the House of Ulloa, a crumbling estate with more pretensions than class. Once he is there, he sees sin when it hits him over the head but always finds excuses to deal with the problems another day. He also finds that the marquis is hardly the one in charge. His attempt to make things better results in the betrayal of the woman he most admires.

This book contains politics, infidelity, domestic violence, corruption with a pinch of gothic on the top. Well done and thought provoking. I'm hoping to find more of Emilia Pardo Bazan's fiction translated into English.

This book contains politics, infidelity, domestic violence, corruption with a pinch of gothic on the top. Well done and thought provoking. I'm hoping to find more of Emilia Pardo Bazan's fiction translated into English.

23Trifolia

Andorra: Andorra by Peter Cameron

The story is set in the idyllic but fictionalized mini-state of Andorra (in reality landlocked in the Pyrenees between France and Spain, in this novel conveniently situated at the sea). The story slowly unwinds as the main character moves to Andorra and meets some people who influence his new life. It all leads to a climax that was interesting though a bit underwhelming. The beauty of this book primarily lies in the wonderful, dreamy setting and the elegant prose, minus points were the characters who were a bit too gimmicky, their stories a bit too plain and predictable. It felt as if the author forgot what he wanted to do with the story and suddenly decided to put an end to it. But all in all, a relaxing, enjoyable read.

The story is set in the idyllic but fictionalized mini-state of Andorra (in reality landlocked in the Pyrenees between France and Spain, in this novel conveniently situated at the sea). The story slowly unwinds as the main character moves to Andorra and meets some people who influence his new life. It all leads to a climax that was interesting though a bit underwhelming. The beauty of this book primarily lies in the wonderful, dreamy setting and the elegant prose, minus points were the characters who were a bit too gimmicky, their stories a bit too plain and predictable. It felt as if the author forgot what he wanted to do with the story and suddenly decided to put an end to it. But all in all, a relaxing, enjoyable read.

24kidzdoc

Spain: Guadalajara by Quim Monzó

Quim Monzó (1952-) is an award winning Catalan novelist, short story writer and journalist who was born in Barcelona, where he continues to reside. This collection of short stories was originally published in 1996, and was subsequently translated into English by Peter Bush for Open Letter Books, who published it last year.

Guadalajara consists of a mixture of surreal, sometimes grotesque, and occasionally wickedly funny tales about the absurdities of everyday life and past and present customs. In the first story, "Family Life", a nine year old boy openly questions a longstanding family ritual on the eve of his ceremony, which leads to unexpected consequences. "Life Is So Short" concerns a chance meeting between a man and a woman who find themselves alone and attracted to each in a temporarily disabled elevator. In "Centripetal Force", a man is unable to leave his apartment on an ordinary day, and his subsequent attempts draw his girlfriend, neighbors and others into his plight.

Also included are several satirical tales about well known characters and stories. In "Gregor", a beetle is suddenly transformed into a boy; in "Outside the Gates of Troy" the Greeks within the Trojan horse are faced with an unexpected complication to their plan to enter the city; and "A Hunger and Thirst for Justice" concerns Robin Hood's attempts to rob the rich, who are increasingly bored by his exploits, and help the local peasants, who question his ethics and are unappreciative of his efforts.

I enjoyed this clever collection of stories, and I look forward to reading his novel Gasoline, which has also been recently published by Open Letter Press.

Quim Monzó (1952-) is an award winning Catalan novelist, short story writer and journalist who was born in Barcelona, where he continues to reside. This collection of short stories was originally published in 1996, and was subsequently translated into English by Peter Bush for Open Letter Books, who published it last year.

Guadalajara consists of a mixture of surreal, sometimes grotesque, and occasionally wickedly funny tales about the absurdities of everyday life and past and present customs. In the first story, "Family Life", a nine year old boy openly questions a longstanding family ritual on the eve of his ceremony, which leads to unexpected consequences. "Life Is So Short" concerns a chance meeting between a man and a woman who find themselves alone and attracted to each in a temporarily disabled elevator. In "Centripetal Force", a man is unable to leave his apartment on an ordinary day, and his subsequent attempts draw his girlfriend, neighbors and others into his plight.

Also included are several satirical tales about well known characters and stories. In "Gregor", a beetle is suddenly transformed into a boy; in "Outside the Gates of Troy" the Greeks within the Trojan horse are faced with an unexpected complication to their plan to enter the city; and "A Hunger and Thirst for Justice" concerns Robin Hood's attempts to rob the rich, who are increasingly bored by his exploits, and help the local peasants, who question his ethics and are unappreciative of his efforts.

I enjoyed this clever collection of stories, and I look forward to reading his novel Gasoline, which has also been recently published by Open Letter Press.

25StevenTX

SPAIN:

Fortunata and Jacinta by Benito Pérez Galdós

First published in Spanish as Fortunata y Jacinta 1887

English translation by Agnes Moncy Gullón 1986

Fortunata and Jacinta is widely considered to be the greatest Spanish novel of the 19th century. The setting is Madrid in the 1870s, a time of great political turmoil. While the novel references some of the historical events taking place at the time, its focus is an intensely detailed and realistic portrait of the characters who inhabit it.

Juan Santa Cruz, the spoiled only child of a prosperous merchant family, has grown up to become an idle playboy. The latest object of his attentions is Fortunata, the beautiful and free-spirited niece of a local market vendor. She becomes his mistress. Appalled at the possibility of a connection to someone so far below their own social level, Juan's parents hustle him into courtship and marriage. His bride is Jacinta: pretty, refined, saintly, and loving. For a while, Jacinta makes her husband forget about Fortunata.

Meanwhile, Fortunata has caught the eye of Maximiliano Rubín, a sickly young pharmacy student. "Maxi," pious and chaste, makes it his project to redeem Fortunata from her poverty and her sinful past. He is determined to make her his wife, even though she confesses she can never love such a pathetic creature. Besieged by a flood of priestly advice from all sides, Fortunata consents to a loveless marriage to save her soul. But once she's another man's wife, Juan Santa Cruz, bored with Jacinta, comes back into her life. The ecstasy and anguish she has experienced in the past is nothing compared with what's to come.

Fortunata is the novel's pivotal character and its central idea. Crude and illiterate, yet beautiful and artlessly charming, violent yet loving, spiteful but forgiving, she both enchants and exasperates everyone around her. Everyone is always trying to change Fortunata--to reform her, tame her, and educate her--and she is always trying to change herself. Yet in the end, one closest to her admits that all these efforts were in vain:

The intractability of human nature is demonstrated in the public sphere as well as the private. During the period of Fortunata and Jacinta Spain went through several governments, from monarchy to republic and back to monarchy. These events aren't directly shown in the novel--the characters' lives are remarkably unaffected, in fact, by their country's state of virtual anarchy--but we see opinions and convictions vacillate as frequently as the political winds change. Just as Juan Santa Cruz always wants the woman he shouldn't have, the public is always in favor of the faction that is out of power at the moment.

Fortunata and Jacinta is about a place almost as much as it is about people. Pérez Galdós describes Madrid in loving detail: the rhythms of daily life, the sounds and smells of the market place, the ebb and flow of trade, the traffic jams and quiet alleyways, the hullabaloo of café society. The physical world is constantly a part of the novel in the texture of clothing, the taste of a confection, the distant sound of a piano, and the vibration from booted feet climbing the stairs.

Pérez Galdós writes in the realist tradition of Balzac, depicting human nature and behavior as he sees it. It is up to the reader to decide if Fortunata is a devil or an angel. The author is transparent and non-judgmental, providing physical description and letting his characters' thoughts and speech convey feelings and ideas. This does make for some long and relatively uneventful passages, and there are some prolonged and not indispensable side trips into the affairs of some lesser characters. In the end, though, Fortunata and Jacinta is a rewarding novel, not as great as, but similar in many ways to Tolstoy's Anna Karenina.

Fortunata and Jacinta by Benito Pérez Galdós

First published in Spanish as Fortunata y Jacinta 1887

English translation by Agnes Moncy Gullón 1986

Fortunata and Jacinta is widely considered to be the greatest Spanish novel of the 19th century. The setting is Madrid in the 1870s, a time of great political turmoil. While the novel references some of the historical events taking place at the time, its focus is an intensely detailed and realistic portrait of the characters who inhabit it.

Juan Santa Cruz, the spoiled only child of a prosperous merchant family, has grown up to become an idle playboy. The latest object of his attentions is Fortunata, the beautiful and free-spirited niece of a local market vendor. She becomes his mistress. Appalled at the possibility of a connection to someone so far below their own social level, Juan's parents hustle him into courtship and marriage. His bride is Jacinta: pretty, refined, saintly, and loving. For a while, Jacinta makes her husband forget about Fortunata.

Meanwhile, Fortunata has caught the eye of Maximiliano Rubín, a sickly young pharmacy student. "Maxi," pious and chaste, makes it his project to redeem Fortunata from her poverty and her sinful past. He is determined to make her his wife, even though she confesses she can never love such a pathetic creature. Besieged by a flood of priestly advice from all sides, Fortunata consents to a loveless marriage to save her soul. But once she's another man's wife, Juan Santa Cruz, bored with Jacinta, comes back into her life. The ecstasy and anguish she has experienced in the past is nothing compared with what's to come.

Fortunata is the novel's pivotal character and its central idea. Crude and illiterate, yet beautiful and artlessly charming, violent yet loving, spiteful but forgiving, she both enchants and exasperates everyone around her. Everyone is always trying to change Fortunata--to reform her, tame her, and educate her--and she is always trying to change herself. Yet in the end, one closest to her admits that all these efforts were in vain:

I wasn't the only one who was deceived; she was, too. We defrauded each other. We didn't take nature into account, the grand mother and teacher who rectifies the errors of those of her children who go astray. We do countless foolish things and nature corrects them. We protest against her admirable lessons, which we don't understand, and when we want her to obey us, she grabs us and smashes us to bits, as the sea does whoever tries to rule it.

The intractability of human nature is demonstrated in the public sphere as well as the private. During the period of Fortunata and Jacinta Spain went through several governments, from monarchy to republic and back to monarchy. These events aren't directly shown in the novel--the characters' lives are remarkably unaffected, in fact, by their country's state of virtual anarchy--but we see opinions and convictions vacillate as frequently as the political winds change. Just as Juan Santa Cruz always wants the woman he shouldn't have, the public is always in favor of the faction that is out of power at the moment.

Fortunata and Jacinta is about a place almost as much as it is about people. Pérez Galdós describes Madrid in loving detail: the rhythms of daily life, the sounds and smells of the market place, the ebb and flow of trade, the traffic jams and quiet alleyways, the hullabaloo of café society. The physical world is constantly a part of the novel in the texture of clothing, the taste of a confection, the distant sound of a piano, and the vibration from booted feet climbing the stairs.

Pérez Galdós writes in the realist tradition of Balzac, depicting human nature and behavior as he sees it. It is up to the reader to decide if Fortunata is a devil or an angel. The author is transparent and non-judgmental, providing physical description and letting his characters' thoughts and speech convey feelings and ideas. This does make for some long and relatively uneventful passages, and there are some prolonged and not indispensable side trips into the affairs of some lesser characters. In the end, though, Fortunata and Jacinta is a rewarding novel, not as great as, but similar in many ways to Tolstoy's Anna Karenina.

26kidzdoc

PORTUGAL

The Missing Head of Damasceno Monteiro by Antonio Tabucchi

This literary thriller opens in a gypsy settlement outside of Oporto, Portugal. Manolo, one of the older men in the village, takes his usual early morning walk in the woods, and finds a headless body that was not there the day before. He notifies the Guardia Nacional, the police department in Oporto, and the crime is reported by the local media. Firmino, the crime reporter for O Acontecimento, a sensationalist rag in Lisbon, is sent to interview Manolo and investigate the murder. With the help of a local and well connected owner of a pension, he meets Manolo and a witness to the crime, and discovers that their accounts differ significantly from the ones provided by the Guardia Nacional officers that arrested the young man, who is subsequently identified as Damasceno Monteiro. Firmino is subsequently introduced to Loton, a morbidly obese lawyer and polymath, who comes from a wealthy family but has dedicated his life to representing the downtrodden of Oporto in court. Loton serves as an adviser to Firmino and his investigation, while in turn Firmino helps Loton with the case. The two engage in interesting but occasionally obtuse philosophical discussions about society, the unequal distribution of justice, and the use of torture to maintain and control individuals.

While I didn't enjoy Damasceno Monteiro as much Pereira Declares, Tabucchi's masterpiece, it was a very good mystery novel with interesting characters and a solid plot line.

The Missing Head of Damasceno Monteiro by Antonio Tabucchi

This literary thriller opens in a gypsy settlement outside of Oporto, Portugal. Manolo, one of the older men in the village, takes his usual early morning walk in the woods, and finds a headless body that was not there the day before. He notifies the Guardia Nacional, the police department in Oporto, and the crime is reported by the local media. Firmino, the crime reporter for O Acontecimento, a sensationalist rag in Lisbon, is sent to interview Manolo and investigate the murder. With the help of a local and well connected owner of a pension, he meets Manolo and a witness to the crime, and discovers that their accounts differ significantly from the ones provided by the Guardia Nacional officers that arrested the young man, who is subsequently identified as Damasceno Monteiro. Firmino is subsequently introduced to Loton, a morbidly obese lawyer and polymath, who comes from a wealthy family but has dedicated his life to representing the downtrodden of Oporto in court. Loton serves as an adviser to Firmino and his investigation, while in turn Firmino helps Loton with the case. The two engage in interesting but occasionally obtuse philosophical discussions about society, the unequal distribution of justice, and the use of torture to maintain and control individuals.

While I didn't enjoy Damasceno Monteiro as much Pereira Declares, Tabucchi's masterpiece, it was a very good mystery novel with interesting characters and a solid plot line.

27rocketjk

Spain

I finished and reviewed Sepharad by Spanish writer Antonio Munoz Molina. Although not all of the book takes place in Spain it really revolves around Spanish culture and history, especially regarding the 20th century consequences of the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. That's a wholly inadequate description of an intensely wonderful book.

I finished and reviewed Sepharad by Spanish writer Antonio Munoz Molina. Although not all of the book takes place in Spain it really revolves around Spanish culture and history, especially regarding the 20th century consequences of the expulsion of the Jews in 1492. That's a wholly inadequate description of an intensely wonderful book.

28kidzdoc

SPAIN

A Thousand Morons by Quim Monzó

Quim Monzó is one of the most highly regarded contemporary Catalan authors, who has only recently been recognized in the English speaking world thanks in large part to Open Letter Books, which has published three of his books in translation in the past three years, Gasoline, Guadalajara, and A Thousand Morons. Although he has written several novels, articles and essays, he is best known in Spain and Europe for his short stories, which are generally surreal and comedic works filled with identifiable characters who find themselves in absurd situations, largely of their own doing.

A Thousand Morons, originally published in 2007, is the latest collection of short stories by Monzó to be translated into English. The first portion of the book consists of longer works, such as "Mr. Beneset", in which a man visits his somewhat unorthodox father in an old people's home, and "Love Is Eternal", about a man who decides to marry his apparently dying girlfriend, whereas most of the stories in the second part are less than five pages in length, including "Next Month's Blood", where the archangel Gabriel receives a surprise when he tells Mary that God has decided to bless her with a son, and "A Cut", in which a boy with a large neck wound is upbraided by his teacher for interrupting class and spilling blood on the floor.

Monzó excels in portraying an ordinary character in a everyday situation that slowly unfolds into a wickedly surreal one. My favorite was "Saturday", a story about a woman who progressively gets rid of everything was owned by and reminds her of her former husband, but then goes just a bit overboard in the process.

I thoroughly enjoyed this short story collection, and I look forward to reading the other three books by Monzó that I already own.

A Thousand Morons by Quim Monzó

Quim Monzó is one of the most highly regarded contemporary Catalan authors, who has only recently been recognized in the English speaking world thanks in large part to Open Letter Books, which has published three of his books in translation in the past three years, Gasoline, Guadalajara, and A Thousand Morons. Although he has written several novels, articles and essays, he is best known in Spain and Europe for his short stories, which are generally surreal and comedic works filled with identifiable characters who find themselves in absurd situations, largely of their own doing.

A Thousand Morons, originally published in 2007, is the latest collection of short stories by Monzó to be translated into English. The first portion of the book consists of longer works, such as "Mr. Beneset", in which a man visits his somewhat unorthodox father in an old people's home, and "Love Is Eternal", about a man who decides to marry his apparently dying girlfriend, whereas most of the stories in the second part are less than five pages in length, including "Next Month's Blood", where the archangel Gabriel receives a surprise when he tells Mary that God has decided to bless her with a son, and "A Cut", in which a boy with a large neck wound is upbraided by his teacher for interrupting class and spilling blood on the floor.

Monzó excels in portraying an ordinary character in a everyday situation that slowly unfolds into a wickedly surreal one. My favorite was "Saturday", a story about a woman who progressively gets rid of everything was owned by and reminds her of her former husband, but then goes just a bit overboard in the process.

I thoroughly enjoyed this short story collection, and I look forward to reading the other three books by Monzó that I already own.

30kidzdoc

>29 rocketjk: Catalan.

31Trifolia

SPAIN

Eenzaamheid (Solitud) by Victor Catala (ps. Caterina Albert i Paradía) (1904) - 3,5 stars

In my search for a suitable book for my personal Reading Through Time-challenge, I found this wonderful book, written by a Catalan author. It's quite a simple story about a young woman who moves to the Spanish Pyrenees with her husband, a lowlife who's not worthy of her. She has to get used to the rugged life in a desolate landscape and harsh living-conditions. Helped by an old shepherd, she finds consolation in the dramatic nature surrounding her but after a crisis, she decides to leave the Pyrenees.

This is a book that I find typical for the early 1900s, with a lot of naturalism and symbolism where nature plays its own role in the story and interacts with the feelings and thoughts of the woman. I like this kind of book, once and awhile, but not too often, as it can become a bit heavy. But, all in all a good book.

Eenzaamheid (Solitud) by Victor Catala (ps. Caterina Albert i Paradía) (1904) - 3,5 stars

In my search for a suitable book for my personal Reading Through Time-challenge, I found this wonderful book, written by a Catalan author. It's quite a simple story about a young woman who moves to the Spanish Pyrenees with her husband, a lowlife who's not worthy of her. She has to get used to the rugged life in a desolate landscape and harsh living-conditions. Helped by an old shepherd, she finds consolation in the dramatic nature surrounding her but after a crisis, she decides to leave the Pyrenees.

This is a book that I find typical for the early 1900s, with a lot of naturalism and symbolism where nature plays its own role in the story and interacts with the feelings and thoughts of the woman. I like this kind of book, once and awhile, but not too often, as it can become a bit heavy. But, all in all a good book.

32kidzdoc

SPAIN

Lizard Tails by Juan Marsé

This clever and strangely beautiful novel is set in Barcelona in 1945, as World War II draws to a close and Generalísimo Francisco Franco is slowly and brutally gaining control over the remaining opposition to his fascist rule of Spain. The book is narrated by the unborn child of Rosa, a beautiful redhead whose husband has disappeared after he is sought by police on the suspicion that he is participating in subversive political activities. The unnamed fetus communicates with his brother David, a 14 year old who unabashedly loves, supports and protects his mother while blaming the fetus for her failing health. David also engages in surreal conversations with his missing father, a British fighter pilot whose poster hangs on the wall of his room, and his older brother. At the same time he befriends Paulino, an equally troubled boy of his age, and attempts to protect his mother from Inspector Galván, a widower who is investigating his father's disappearance while he showers Rosa with attention and gifts.